Let's make a mutual confession: We love dividends. As an investor, you wouldn't be reading this if you didn't have a deep affinity for those regular quarterly payments that are so darn fun to collect. The problem, of course, is that it's easy to find a dividend-paying stock, but hard to find the best dividend paying stocks -- Here's how I go about analyzing dividend candidates for my portfolio.

Step 1: Cull the herd

There are a lot of companies that pay dividends, and many possess huge yields. But just paying a dividend isn't enough, even if it's a big one. There needs to be a trend that suggests rewarding investors on a regular basis is important to a company. Which is why my first step is to look only at companies with a history of regular annual dividend hikes.

My first cut is always those companies with streaks of 25 years or more -- that's real commitment! But I don't stop there. I also look at companies with at least 10 years of annual dividend hikes -- not as good, but still impressive. These two moves alone will slim down the names you have to look at while focusing on the types of companies that have proven through their actions that you, the shareholder, count.

Step 2: Give a little leeway

A business rarely grows in a straight line; a sine curve is far more normal. And 10 years is a long time to wait before at least recognizing that a company is a solid dividend payer. Which is why I also step back and look at companies that have five years of annual dividend growth under their belts. Here you are looking for two different types of companies, up-and-comers and fallen angels.

Although I generally don't buy companies that have only recently started to pay a dividend, preferring to wait for the 10-year mark, dividends tend to grow fastest in the early years. So, for dividend growth investors, looking at companies with at least five years of increases is a worthwhile effort. For me, it's more about information -- what companies are working their way up to my target range?

I'm more interested in fallen angels. These are companies that ran into some problem and had to either cut their dividend, or hold it steady for a year or two. If it's back up to five years of increases, there's a good chance the business is on the mend. The key is to understand what happened.

ETN Dividend Per Share (Quarterly) data by YCharts.

A great example from my own portfolio is global industrial giant Eaton Corp. (ETN 1.54%). After more than a decade of annual hikes, it took a short pause following the biggest acquisition in its long history. Once it got that deal under its belt, it starting hiking again. I was willing to overlook that "transgression" since it made the company stronger in the long run, the dividend didn't actually get cut, and Eaton quickly got back on the dividend-hiking bandwagon.

Step 3: Is the yield enough for me?

My next step is to focus on companies with yields over 4%. That's my sweet spot; yours might be higher or lower. The reason I use 4% is because of the old retirement rule that if you pull 4% a year from your portfolio in retirement, you can reasonably expect it to last until you're dead. I figure if I've got a 4% yield, on average, then I don't even need to touch my portfolio -- I just need to keep collecting those quarterly dividend checks. (More on how willing I am to violate this step later.)

Step 4: Is it a good deal?

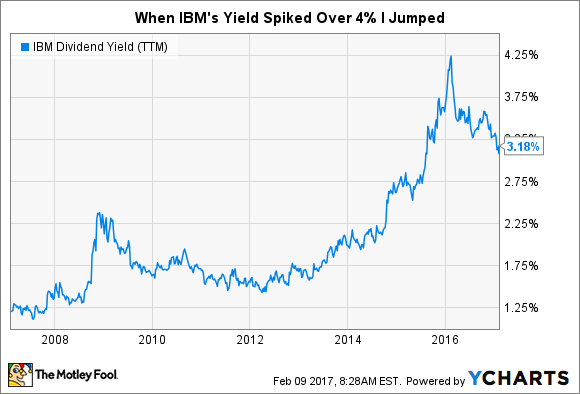

The next thing I look at is a company's yield relative to its own history. Just having a 4% yield doesn't tell you enough. If you're looking at a utility, 4% could actually be a relatively low number. If it's International Business Machines (IBM 0.16%), though, 4% would be a relatively high number.

Image source: IBM.

Essentially, I'm using yield relative to history as a rough estimate for valuation. If the yield is at the high end of a company's historical range, it's a good bet the price is relatively cheap. There will probably be a reason for it, which is the next step, but focusing on names that are relatively cheap compared to their own histories will help you get a good price in addition to a good yield.

Another thing I do here is to perform a reverse dividend discount model analysis. This sounds far more interesting than it really is. Basically, I look at what dividend growth is being priced into the current stock price. I compare that to the company's own history and what I'd like to see (at least 3% growth over the long term so I can keep up with the historical rate of inflation). Doing this keeps me out of the game of trying to predict the future. All I have to decide is whether or not I'm willing to accept what Mr. Market is offering up today.

Step 5: What's wrong?

I noted that business trends usually move in a sine curve above, which also means you have to ask why a company's yield is at the high end of its historical range. There are, clearly, a vast array of possible reasons. It could be as simple as an industrywide downturn, or a real risk of a dividend cut and/or bankruptcy. You need to get your head around the business, its current results, and the company's long-term outlook.

IBM Dividend Yield (TTM) data by YCharts.

For example, I knew IBM was struggling with a business shift when I saw its yield spike over 4%. I bought the stock because IBM has gone through business transitions like this many times before in its over 100-year history. And, despite the current troubles, it was still generating huge amounts of cash. So, 20 years of annual hikes, still financially strong, and a history of successfully navigated transitions -- I pulled the trigger. But not before going through the next three steps.

Step 6: Kill the company

Even if a company has made it all the way down to this point, I'm still not satisfied. I now ask what could go wrong. I run through a list I basically stole from Bruce Berkowitz of the Fairholme Fund (FAIRX). I try to avoid companies that don't generate cash, that burn too much cash, that have too much debt, that take big risks (even if there are potentially big rewards), that have questionable management teams, that have weak boards, that expand/diversify into unrelated or just plain bad businesses, that are careless with stock buybacks, and that abuse GAAP accounting standards in some way.

That's a lot to go through, so take your time. But, if you work through the list point by point, you'll cull out the names that look like great ideas, but are just too risky to touch. That said, there are a lot of subjective judgements to make. For example, IBM was buying back stock even when its stock price was falling -- is that good or bad? And it has been buying companies to expand into new business areas -- good or bad?

My answer to those questions was positive; yours might be negative. The real point of the Berkowitz kill list, though, is to force yourself to ask and answer the questions. It's a self-check that makes you second-guess your choices.

Step 7: Violate step 3

At this point, I'm pretty well along the way to buying a stock. But I would be remiss if I didn't bring us all the way back to Step 3. On a big picture level, I'm looking for what I consider to be great companies at good prices. I'm using the dividend to suss that out. However, there are companies I believe to be great but that historically have yields well below 4%. For example, Disney (DIS 1.54%) and Hormel (HRL).

DIS Dividend Yield (TTM) data by YCharts.

I know the stories behind Disney and Hormel, and I would be very happy to own them. They are on my short list of stocks to watch. The difference is that I have to lower my yield expectations and look for a time when their yields relative to their own histories are great -- but below 4%. No rule is hard and fast when it comes to investing, and I'm willing to compromise on yield for companies I think are financially strong leaders with great futures.

Step 8: What if I'm not around...

After so many steps, you'd think I'd just buy a stock already! But, no, I have one more step, and it's the most important of them all. I ask myself, "Would I want my wife to own this stock if I were to die?"

That sounds kind of macabre, and maybe it is, but my wife isn't as interested in investing as I am. And I'm no longer 20 years old with few responsibilities. I'm over twice that age, and I have a family to think about, along with everything else that comes with being my age.

For example: I'm OK with my wife owning IBM if I weren't around. I trust that she would keep track of it and understand the big picture. But I wasn't OK with her owning Helmerich & Payne (HP 2.64%). Helmerich & Payne is a great company, but it operates in the highly cyclical oil and gas drilling services sector. I'm not nearly as certain that my wife would be able to handle the ups and downs of that business; heck, I'm not sure I would be able to handle them. So, I passed on Helmerich & Payne when its yield spiked during the oil downturn that started in mid-2014.

We're all different

That's a rough overview of how I go about finding dividend stocks for my portfolio. After so many steps, you might not believe I ever buy a stock, but I do -- honest. I just don't buy too many.

That said, the steps I've outlined aren't comprehensive; I toss some other things in from time to time. For example, I sometimes look at the Graham number to identify cheap stocks -- it's just not a core activity in my process. The eight steps I've outlined really summarize the high points and will focus you on truly great dividend stocks.

Feel free to use all of my steps, or just pull out just the ones that are right for you (I highly recommend you use the Berkowitz kill list). In the end, the goal is to find what makes sense in your world -- otherwise, you won't follow through. At the very least, give these steps a try and see if they get you as focused as they get me on the best dividend stocks around.