Image source: Netflix.

It seems that $800 billion wasn't quite enough money for Netflix (NFLX -2.52%). Instead, the company just boosted its debt offering to a cool $1 billion after plenty of buyers volunteered to loan the streaming video giant some cash.

The size and timing of the debt sale might seem odd for two reasons. First, Netflix just announced blockbuster third-quarter earnings results powered by strong subscriber growth. The user gains translated into much higher earnings, too. Netflix posted a 43% spike in operating income, as its profit margin jumped to 5% from 3%.

Second, CEO Reed Hastings and his team reiterated their forecast of "generating material global profits" beginning next year as international markets mature, and as the latest round of price hikes supercharge results. So why does Netflix need so much new debt when earnings are trending higher and significant profitability is just months away?

Earnings aren't cash

It's important to understand exactly what Netflix means when it promises to produce significant profits starting next year. The company hasn't targeted specific numbers, but presumably they are above the break-even figures it has achieved lately.

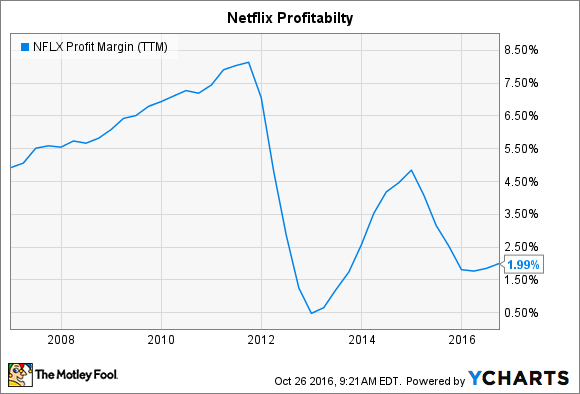

Netflix earned $123 million last year, which translates into a profit margin of less than 2%. Bottom-line profitability had been creeping toward double digits until 2012, when the company started aggressively expanding the reach of its streaming business.

NFLX Profit Margin (TTM) data by YCharts.

Now that the service is available essentially everywhere (except China), Netflix is free to allow more of its operating profits to flow down to the bottom line, pushing net profit margin back up toward double digits.

But Netflix isn't projecting significant cash flow in the near future. On the contrary, the company expects to burn through $1.5 billion this year. In 2017, when profits are improving, the cash picture should brighten, too, but not by much. "As we're able to raise operating income," Chief Financial Officer David Wells told investors, "we'll be able to fund more of that [content spending] organically."

Staying flexible

Netflix's huge appetite for cash is dictated by its aggressive original content strategy. It plans to release over 1,000 hours of high-quality original programming next year, up from 600 hours in 2015, and 300 hours in 2014. Unlike licensed shows and movies, this content requires huge upfront cash payments.

Image source: Netflix.

There are significant returns to accepting more of the production and cash risks, though. Its ownership of Stranger Things, for example, gave management flexibility to broadcast the show globally, produce it at a lower cost, and maintain its exclusivity on the Netflix service.

Additionally, Netflix is increasingly opting for more control over its originals. This year's hit Stranger Things was self-produced, which required even more of an early commitment than a licensed original like Orange is the New Black.

"While it does require more cash up front to fund the development process, we find it's a great trade-off for cash," according to Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos.

Flexibility is broadly what the latest $1 billion loan is all about. Sure, earnings are headed higher internationally and the U.S. subscriber base is almost fully migrated to the higher-priced monthly plans. But Netflix would rather have more cash available in case management decides to boost original content spending to ignite growth in a promising market.

Will this be the last loan?

Netflix has made a habit of dipping into the credit markets once a year lately. It took on $1.5 billion of debt in 2015, and in each of the prior two years, the figure was about $500 million. There's a chance that this recent offering will be Netflix's last -- thanks to improving profits and the lack of additional market launches. It's likely, though, that management just continues to use this financial tool as a means of amassing control over its portfolio as it morphs into an exclusive-content specialist that produces most of its own shows and movies.