If you're in the market for a gold and silver stock, you could buy a miner. But that would be missing a key part of the precious metals industry that might be a better option for you. The niche sector you're overlooking is the streaming and royalty business, where Silver Wheaton (WPM 2.75%), Franco-Nevada (FNV 2.53%), and Royal Gold (RGLD 1.61%) are three of the biggest players. Here's how they're different and why you might want to own one, or more, of them.

Mining and not

Precious metals mining is a pretty straightforward thing: You dig up gold and silver and sell it. Obviously, it's more complex than that, but those are the basics. Gold and silver streaming companies don't do that. Instead, they provide money up front for miners in return for the right to buy gold and silver at reduced rates in the future. For example, Silver Wheaton pays roughly $4 an ounce for silver and $400 an ounce for gold, way below the current spot price for each metal.

Image source: Royal Gold, Inc.

It's understandable that Silver Wheaton would want to lock in low prices, but why would a miner want to sell silver and gold on the cheap? There are a number of possible answers. If precious metals are in a slump, then the market price for mining stocks is likely to be depressed, so selling stock would be a less-than-desirable avenue for raising cash. Undesirable interest rates in the bond market or from banks could push miners toward streaming deals, too. So, if a miner needs cash to shore up its balance sheet or fund a new mine, streaming companies could be the most economic option.

Then there's the situation in which gold and silver are just byproducts of mining for some other metal. A good example of this is the 2015 gold streaming deal Royal Gold inked with Teck Resources (TECK 0.15%). The $525 million agreement was related to the Carmen de Andacollo mine, which is primarily a copper mine. In fact, Teck's main businesses are metallurgical coal, copper, and zinc. Teck was just monetizing an asset that really wasn't all that important to the company, pushing forward income that it would have otherwise taken years to earn.

A quick overview of the streaming process. Image source: Silver Wheaton.

The implication

So, Silver Wheaton, Franco-Nevada, and Royal Gold aren't miners. That means you have to think about them a little bit differently since they are more like specialty finance companies.

For example, the recent commodity downturn was a great time for this trio. Giant miners were struggling financially, desperate for cash, and eager to make deals. To put some numbers on that, Franco-Nevada's production was up a massive 29% in 2016, hitting an all-time record because of the deals it was able to ink with troubled miners during the precious metals downturn. So, when miners are struggling, streaming companies can actually benefit.

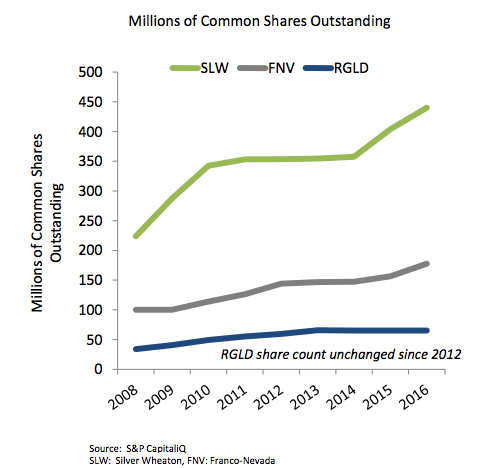

But how does that growth get funded if gold and silver prices are low? Although cash from operations is a part of the story, another big piece of the puzzle is using short-term debt to ink a streaming or royalty deal, and then issuing stock to permanently fund the transaction. That means you need to keep an eye on share count -- and potential shareholder dilution. Royal Gold, for example, made a point of telling shareholders at its annual meeting that it had issued fewer new shares than Silver Wheaton or Franco-Nevada during the commodity downturn.

Royal Gold has been stingy with the shares. Image source: Royal Gold.

What about when large miners have easier access to other funding options? In those situations, streaming companies may find themselves dealing with secondary miners and projects that are in earlier stages of development. That's not bad, but there are more risks involved, including mines that just don't pan out as expected, and miners that hit a financial wall. There are contract stipulations that can limit the pain of a mistake, like requiring the return of money if things don't go well, but the time that a streaming company's capital was tied up in a bad investment can't be made up. Silver Wheaton, for example, has invested in Barrick Gold's Pascua Lama mine -- this mine has been bogged down in legal, social, and environmental red tape for years and is still nowhere near completion.

The whole, not parts

It's probably best for you to think of a streaming company's investments as a portfolio. Silver Wheaton, Franco-Nevada, and Royal Gold are always trying to find the right mix of producing assets and developing assets that will lead to top- and bottom-line growth. Complicating the math is that mines have limited lives, so they also have to keep replacing production from mines that are petering out.

Franco-Nevada's game plan. Image source: Franco-Nevada.

And then there's the often volatile price of silver and gold. It's a complex process, and one you have to consider as a whole, looking at things like mine diversification and expected production from up-and-coming investments. And always remember that it's much easier for Silver Wheaton, Franco-Nevada, and Royal Gold to buy and sell a streaming contract than it is for a miner to buy or sell a mine, so things can change relatively quickly. That's a big plus in my book.

All of that said, if you're looking for a precious metals investments, the differences here could be exactly what you're looking for -- like owning a gold and silver company that can actually benefit from low precious metals prices. But you have to make sure you understand how Silver Wheaton, Franco-Nevada, and Royal Gold are different from miners like Teck and Barrick, otherwise you won't truly understand what you own.