Insurance stocks won't double in a day, but they can make buy-and-hold investors wealthy over the long haul. High-quality insurance companies can generate incredible long-run returns from a business that dates all the way back to ancient Greece.

Some of the industry's best performers are detailed in the table below, complete with their annual compounded returns over the last 15 years.

|

Insurance Company |

15-Year Compounded Return |

|---|---|

|

RLI Corp. (RLI -0.69%) |

15% |

|

Progressive Insurance (PGR 1.32%) |

13% |

|

Markel Insurance (MKL -0.38%) |

12% |

|

Total stock market index |

10.2% |

Data source: DQYDJ stock return calculator. Calculations assume dividends are reinvested. Vanguard index fund used as a benchmark for total stock market return.

Though the industry may have its own jargon and complex financials, time spent learning about the insurance industry is time very well spent. The industry's best operators have generated returns well above the total stock market average, and I expect that the best operators will continue to trounce the market over time.

Sticking with what's knowable

In this article, we'll look primarily at property and casualty insurers because they are by far the easiest for outsiders to analyze and understand. Property and casualty insurers are companies that insure property from damage, theft, or loss, and protect people from liability when they cause damage to someone else or someone else's property.

Car insurance is a classic property and casualty insurance line, as is homeowners insurance. But there are also some rather interesting types of P&C insurance, like insurance for snowmobiles or thoroughbred horses, just to name some oddballs.

Image source: Getty Images.

Property and casualty insurers are easy to analyze because they underwrite short-tail insurance lines. This means that claims for losses are usually made during the policy period or shortly thereafter. A car insurance customer might get in a fender bender in March, and all of the damage will have been tallied and paid for by the end of April. At worst, a really bad accident might take a couple years to clear, as a sea of medical and legal bills finally come to a close.

Long-tail insurance lines leave far more room for error. In an extreme case, the insurance industry has almost universally lost piles of money on disability insurance because of bad assumptions about how fast healthcare prices would rise over time. Long-tail insurance companies have to provide a quote today for a loss that might occur 15 or 20 years later. No matter how much historical data you have, predicting the future is very hard to do. As a rule, I prefer insurance companies that make shorter-term estimations to insurers who have to look far into the future.

The point is that short-tail insurance lines provide relatively quick feedback as to whether an insurer is pricing risk correctly. From an investment standpoint, this makes analyzing them easier and can give us more confidence about an insurer's loss estimates and the quality of its earnings.

Profits separate the insurance greats from the merely average

The very best insurance companies will make money in two ways. First, insurers can make money by appropriately pricing their policies to reflect the risk of loss and the cost of finding and servicing the needs of their customers. Second, insurers make money by generating a profit from their investment portfolios.

Extraordinarily good insurance companies regularly earn an underwriting profit, which occurs when they pay out less in claims and operating expenses than they earn in premiums. If a company earns $100 in premiums, earmarks $70 for loss reserves, and spends $20 on general and administrative functions, it would have a pre-tax underwriting profit of $10. A pre-tax operating profit margin of 10% is a very good result in the insurance industry, perhaps almost impossibly good. Realistically, a "great" insurance company is one that repeatedly earns an underwriting profit at all.

Very few insurance companies will regularly earn an underwriting profit, but all insurance companies earn money from their investment portfolios. One of the beautiful things about insurance companies is that they collect premiums today for losses that will be paid later. This time difference creates what is known as "float," or cash that the insurance company can invest for its own profit in the meantime.

P&C insurance companies typically invest their float in low-risk bonds, and may generate only generate income equal to a few percentage points of the company's total investment portfolio. That said, in a business where small profit margins are the norm, a few percentage points of investment income can add up.

Ratios you should know

Investors and analysts measure the performance of insurance companies with just three ratios that tell you a lot about the quality of an insurance company. These ratios are the "loss ratio" and the "expense ratio," which are added together to form another ratio called the "combined ratio."

Most insurers calculate these ratios for you when they report earnings, but calculating them on your own is very easy. Here's an example:

Suppose Foolish Insurance Inc. earns $100 of premiums in a given year. During the same year, it records $70 of loss and loss adjustment expenses related to customer claims, and $20 of operating expenses for advertising, utility bills, bookkeepers, and so on.

We can calculate its loss ratio by dividing its insurance losses ($70) by its premiums earned ($100) to arrive at a loss ratio of 70%. The expense ratio is calculated similarly. We divide its operating expenses ($20) by premiums earned ($100) to arrive at the expense ratio of 20%. Finally, we add these two ratios together to arrive at a combined ratio of 90%.

We know that for every dollar this insurer earned in premiums, it incurred losses of $0.70, operating expenses of $0.20, and thus generated a pre-tax operating profit of $0.10. Again, this is a very good result.

Ratios do the heavy lifting

Insurance is largely a commodity business. Buyers search for the lowest premium for a given risk, and generally care very little whether their car insurance cards say "Geico" or "Progressive" at the top. For this reason, insurance companies don't have much pricing power. That means only the best can reliably generate a profit from their underwriting.

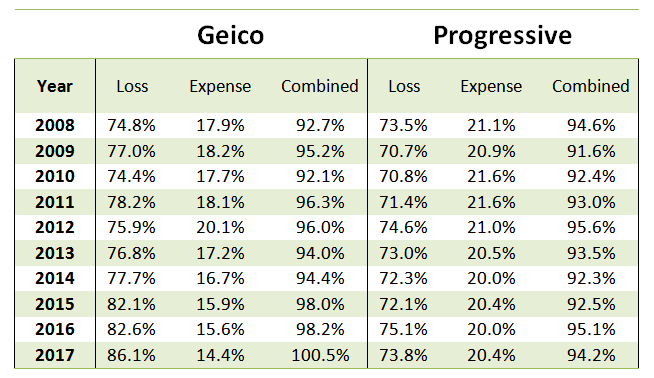

I use Geico and Progressive as examples because they are both very good insurance companies. They have consistently produced underwriting profits in an industry where most companies generate underwriting losses. How GEICO earns its underwriting profit, however, is actually very different than how Progressive does.

Geico is very good at controlling its expenses, but isn't as good at measuring or pricing risk as Progressive. The latter is better than Geico at measuring and pricing risk, but it isn't as good at controlling its operating expenses, in part because it gets a lot of its business from costly insurance agents.

To be clear, I don't know this because I'm an expert on every single insurance line and insurance company. I know this because the loss ratio, expense ratio, and combined ratio I calculated from 2008 through the first nine months of 2017 tell the story for me. (These ratios really are important.)

Image source: Author, with data from SEC filings.

Over a period spanning nearly one decade, Geico always had a lower expense ratio than Progressive. On the other hand, Progressive always had a lower loss ratio than Geico. The three ratios -- loss, expense, and combined ratios -- can do a lot of heavy lifting when it comes to analyzing insurance companies for investment purposes.

Where the money is

Car insurance is an easy example because most people are somewhat familiar with it, but it's a very competitive corner of the insurance world. State regulators often dictate how policies have to be structured and even how they can be priced. Geico's and Progressive's outsize underwriting profits are not the norm. State Farm, the largest U.S. auto insurer, lost $7 billion from underwriting in 2016 alone.

Not all insurance lines are as competitive as car insurance. So-called "specialty" insurance lines are less regulated, and tend to be more profitable for insurers than admitted lines of insurance like car or homeowners insurance. Insurance companies that underwrite specialty insurance lines are a good cohort for investment because they tend to write more difficult risks where relationships and familiarity with the risks matter.

Steve Markel, vice chairman of Markel Insurance, summed up the specialty business better than I ever could in a comment about how Markel works.

If you can think of some insurance product that you need, and you could get a policy for it quickly and easily, well Markel doesn't do that. On the other hand, if you were to answer "no" two or three times to an insurance questionnaire, now that's getting closer to what we like to do. What we do is insure things that are rather complicated and unusual, like children's summer camps, bass boats with overpowered engines, weddings and event cancellations, vacant properties, new medical devices, new technology, or the red slippers Judy Garland wore in the Wizard of Oz. [Emphasis mine.]

He's not joking about the red slippers, by the way. His company really did insure them.

That Markel has historically operated in specialty lines of business is pretty evident from its loss, expense, and combined ratios. In the 30 years since 1986, the year in which it went public, Markel has generated an underwriting profit in all but nine years. In eight years, it booked double-digit underwriting margins.

Markel is just one of many companies earning astounding profits in specialty business lines. RLI Corp. may be the world's best insurance company that few people have ever heard of. It started out in 1965, when it operated as Replacement Lens, Inc., an insurance company for contact lenses. It sounds crazy today, but at the time, contact lenses were expensive enough that consumers wanted to insure them.

Today, RLI specializes in all kinds of specialty insurance lines and hard-to-place risks, but the results have been extraordinary, thanks to low loss ratios. In a typical year, it will incur losses of less than 50% of premiums earned. Of course, turning over a lot of rocks to find good risks is not an inexpensive activity. RLI Corp.'s expense ratio has typically been in the neighborhood of 40% of earned premiums. (Curiously, Markel, through its investment portfolio, actually owns about 2.7% of RLI Corp.)

When thinking about where to invest in insurance, less competitive specialty insurance lines are a great place to look for market-beating stocks, as they are more likely to generate underwriting profits to augment the investment income earned on their float.