After muddling through a disastrous and debt-fueled foray into the energy business, copper and gold miner Freeport-McMoRan Inc. (FCX -1.96%) finally started to turn a corner in 2017. Jettisoning oil and reducing debt got the company back onto solid footing. And then a dispute with the Indonesian government over ownership of the Grasberg copper and gold mine started to boil over. After a year of negotiations, the two sides have yet to come to a final agreement on how to deal with the giant mine. This leads me to wonder, "What does Freeport-McMoRan look like in a worst-case scenario?"

Not the best results

The first-quarter update on the negotiations between Freeport and Indonesia highlighted the broad framework that the two sides agreed on in 2017. Essentially, Indonesia wants to take 51% ownership of the asset so it can benefit more financially from the success of the mine. Freeport has OK'd this, but the two sides haven't actually worked out the details of how to get there. Discussions so far haven't solved the dispute.

Image source: Getty Images.

In early 2018, Indonesia complicated the issue by hitting Grasberg with new environmental demands. Freeport says the demands aren't workable and that the new environmental regulations need to be dealt with before a final agreement can be reached on the ownership issue. In short, negotiations between Freeport and Indonesia do not appear to be going very well. For reference, Rio Tinto, which holds a stake in the mine, is reportedly looking to sell to get out from under the asset and these ownership issues.

A major long-term problem

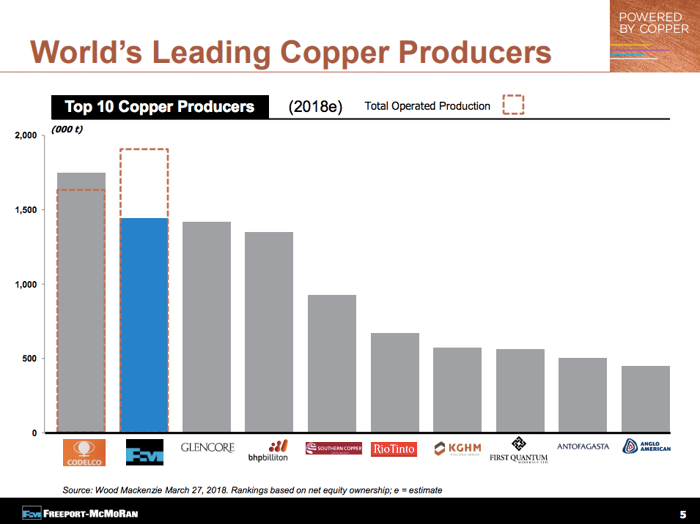

The difficult negotiations are a big problem for Freeport because Grasberg is a very important asset for the company. The mine accounted for roughly a third of its copper production in the first quarter and virtually all of its gold production. If the two sides aren't able to come to terms and Freeport has to walk away from the mine, its quarterly copper production would fall from 952 million pounds to 641 million pounds. It will push Freeport from the world's No. 2 copper producer to No. 5, and gold would no longer be a major metal for the company.

Freeport's stature would decline if Grasberg went away. Image source: Freeport-McMoRan Inc.

However, that's only half the story. Grasberg isn't just a large mine -- it's also a highly profitable mine. The cash cost to produce copper at this mine in the first quarter was 26% below that of its North American operations and 24% lower than the cash costs of its South American business. Add in byproduct credits and Grasberg's cash cost goes deep into negative territory, helping to push the company's average cash cost to less than a dollar in the first quarter. Pull out Grasberg and Freeport's margins will take a big hit.

The size and low-cost structure of Grasberg are the two main reasons the miner is unlikely to walk away from the negotiating table. They are also why the company is not in a great bargaining position. At this point, Freeport is putting forward a scenario in which it remains in Indonesia and transitions majority ownership of Grasberg to the country. That transition isn't pretty for Freeport.

The current projections for Grasberg. Image source: Freeport-McMoRan Inc.

Assuming a deal is reached that matches up with the company's current estimates, copper production from the mine attributable to Freeport will fall from an estimated 1.15 billion pounds in 2018 to just 500 million pounds in 2019. Production would double by 2020 and increase to 1.5 billion pounds in 2021 as capital projects at the mine start to bear fruit. Gold production, meanwhile, would fall from 2.42 million ounces in 2018 to just 650,000 ounces in 2019. And while attributable gold production would start to increase from that point, it doesn't come close to matching the 2018 level. Gold production in 2022, assuming the current broad framework holds, is still 33% below the level projected for 2018.

Not great either way

Freeport-McMoRan is working hard to retain as much value as it can at the giant Grasberg mine. The sheer size of the asset in its portfolio means it has little choice. While it could walk away from Grasberg, the effect on its production and costs would be pretty devastating. That's not likely to happen. But the current outlook for the mine, assuming a deal is reached as currently expected, will mean several difficult years of adjustment -- and that's the best-case scenario at this point. Until there's a final resolution at Grasberg, most investors should stay on the sidelines at Freeport-McMoRan.