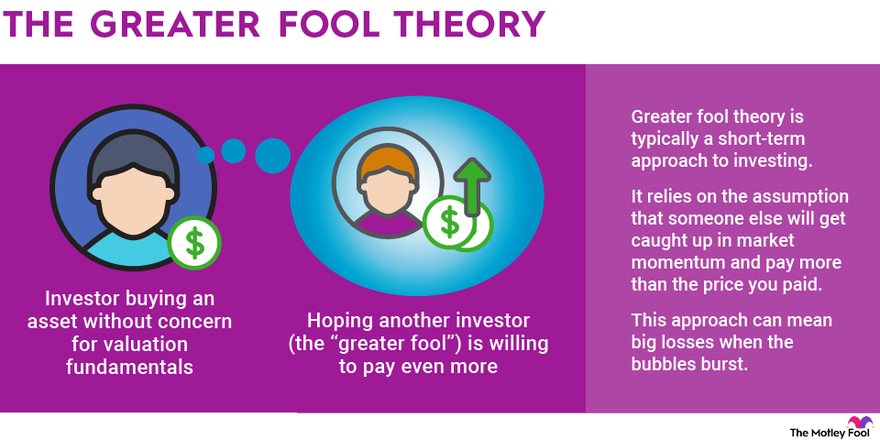

Greater fool theory states that investors can achieve positive returns by buying an asset without concern for valuation fundamentals and other important factors because someone else will buy it at a higher price.

Investors employing this theory may even think assets that they are purchasing are overvalued based on fundamentals or long-term performance outlooks, but they still expect to make a profit because another investor (the "greater fool") will be willing to pay even more.

The greater fool theory in action

The greater fool theory in action

Greater fool theory is typically a short-term approach to investing. Essentially, you are banking on someone else coming along and buying your assets for more than you paid -- without any theory as to why someone would want to pay a higher price.

This philosophy relies on the expectation that someone else will get caught up in market momentum or have their own fundamental case for why the asset is worth more than the price you paid.

If a person buys bitcoin without concern for its use cases, adoption, or underlying technology, simply anticipating someone will buy it later at a higher price, their strategy relies on the greater fool theory. Depending on when this investor buys and sells, they could experience either stellar returns or substantial losses.

The performance of the U.S. real estate market over the last several decades presents another example of the risk-reward dynamics of the greater fool approach. Average inflation-adjusted U.S. housing prices nearly doubled from 1995 through 2005, according to the Federal Reserve. Homebuyers relying on the greater fool theory likely enjoyed strong returns if they purchased and sold at nearly any time during that period. There were no repercussions for the lack of time and energy spent understanding the fundamentals and intricacies of the real estate market.

However, if U.S. homebuyers purchased at the beginning of 2007 with the expectation that the real estate market's impressive momentum would continue unabated, they would have likely watched their property value plummet. Housing prices began moving lower that year, and ultimately hit a bottom in 2011 before beginning to rebound. The average home price in the U.S. didn't match the high that it hit in early 2007 until 2013. A "greater fool" may have eventually come along, but it took roughly six years on average for that to happen -- and many real estate investors wound up selling properties at substantial losses before a fool could come knocking.

Advantages and disadvantages

Advantages and disadvantages of using the greater fool theory

Greater fool theory relies on timing and momentum, and it is possible to enjoy strong returns with this approach. However, without analyzing fundamentals and market forces beyond near-term investor enthusiasm, it's difficult to have a grasp on whether the timing of your purchases will be fruitful.

You shouldn't be surprised if waning excitement among investors for an asset or a shift toward a fundamentals-based valuation leaves you with depreciating assets. Investors buying assets without concern for fundamentals tends to create valuation bubbles, and that can mean big losses when the bubbles burst.

Famous value investor Benjamin Graham once wrote that "in the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it is a weighing machine." Graham was conveying that popular sentiment plays the biggest role in shaping stock market pricing action in the short term, but fundamental factors including revenue, earnings, cash, and debt determine how a company's stock performs over longer periods. It is possible to achieve strong returns by using the greater fool theory, but it's risky and far from the best path to achieving strong long-term performance.