Almost every investor is tempted by the idea of accelerating their returns.

On average, the S&P 500 returns about 9% every year with the dividends reinvested. That's enough to build substantial wealth over a long period of time, and it's a relatively low-risk way of doing it. However, for investors willing to take on more risk, there are ways to increase your potential returns by adding leverage. One of the most popular ways of doing this is trading on margin.

What is margin?

The simple definition of margin is investing with money borrowed from your broker.

There are two primary types of brokerage accounts. In a cash account, you invest your own money. In a margin account, you can borrow from the brokerage based on how much you have invested. When you invest with a margin account, you're able to purchase stocks according to your "buying power," which includes both your own cash and a loan against the money you have invested.

What is margin trading?

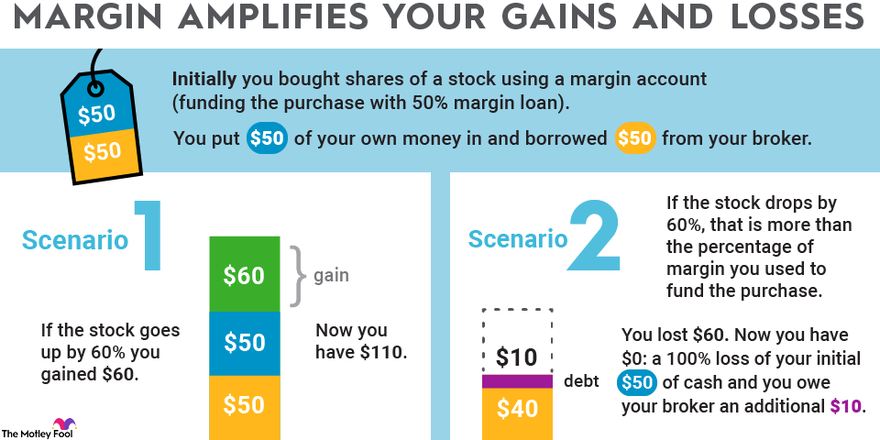

Buying stocks on margin is essentially borrowing money from your broker to buy securities. That leverages your potential returns, both for the good and the bad, and it's important for investors to understand the implications and potential consequences of using margin.

First, using margin means paying interest to your broker for the money you're borrowing. At Fidelity, for example, the interest rate you'll pay on margin balances up to $24,999 is 8.325%. When you compare that rate to the 9% to 10% potential annual return in stocks, you'll quickly recognize that you're taking the risk, but the broker is getting much of the rewards. Because of interest, when you use margin you have to worry about your net profit margin, or your profits after paying interest, which will be less than your investing gains.

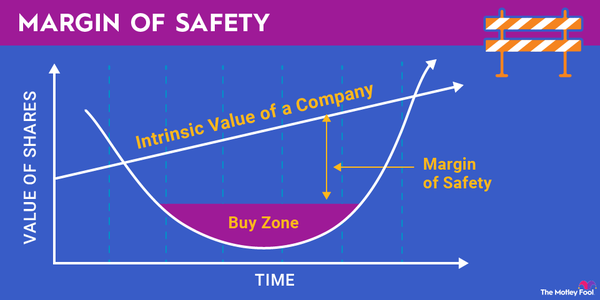

Investors should also be aware that brokerage firms have initial margin requirements, or minimum margin requirements, requiring the investor to put a minimum amount in the account before they can borrow from the broker. At Fidelity, you must put in $2,000 to use margin. In order to buy an individual stock, the margin requirement is 50%, meaning if you want to buy $10,000 of a stock, you have to put in $5,000 in equity. There are also maintenance margin requirements of at least 25% equity, which would apply when account values fall, and that rate may be adjusted depending on how the account performs and broader market volatility.

Buying on margin example

Assume you have $1,000 in cash and want to buy $2,000 worth of a stock that trades at $10 a share. You can put up $1,000 of your own money, borrow $1,000 from your broker, buy 200 shares, and you'd own $2,000 worth of that stock. Your net account balance would still look like you have $1,000, but it would show up as $2,000 in stock and a $1,000 margin loan from your broker.

If the stock went up from $10 to $12, that's a 20% increase above your purchase price. At that point, your 200 shares would be worth $2,400, and your account balance would reflect a total value of $1,400 ($2,400 in stock, minus the $1,000 margin loan). That's a 40% increase to your account value on only a 20% increase in the stock price.

Of course, margin cuts both ways. Say that stock instead dropped 20%, from $10 to $8. At that point, your 200 shares would be worth $1,600, and your account balance would reflect a total value of $600 ($1,600 in stock, minus the $1,000 margin loan). That's a 40% decrease to your account value on only a 20% decrease in the stock price.

There's a bigger risk in margin trading than simply losing more money than you otherwise would have.

What is a margin call?

When you have a margin loan outstanding, your broker may issue something known as a margin call, particularly if the market moves against you. When you get a margin call, your broker can demand you pony up more cash or sell out positions you currently own in order to satisfy the call. If you can't cover the call, your broker will liquidate your positions to get it covered.

If your broker starts selling out your positions, that broker doesn't care about your tax situation, your view of the company's long-term prospects, or anything else other than satisfying the call. If the market really moves against you -- say the company whose stock you bought on margin declared bankruptcy and the stock became worth $0 -- you're still on the hook for your borrowed funds.

Why buying on margin is a bad idea

Short-term movements in the market are almost impossible to predict, and there's always the risk of a black swan event like the coronavirus pandemic crashing the market. While the upside of margin trading may seem appealing, the downside risk is much greater.

As an investor, you have no control over the timing of a margin call, and you can fall victim to one even if it's just from a short-term movement. Even if you still believe that a stock will recover, and it does, you could still be forced to liquidate, meaning you missed out on gains you would have gotten if you were using an ordinary cash account.

Additionally, the interest payments and maintenance requirements add other costs and risks. Especially for beginning investors, it's best to avoid trading on margin since it's not always clear how much you've borrowed from your brokerage and how much you have in equity, plus it's easy to think of all of your holdings as your money even if much of it is borrowed. Remember that it's beneficial to your broker for you to use a margin account since it's an easy way for them to make money, so it's in their interest to encourage you to do so.

The recent events with WallStreetBet stocks like GameStop (GME 3.28%) offer the best argument for not using margins. It's easy to get sucked into such trades when the stock is skyrocketing, but GameStop just as quickly reversed, leaving thousands of traders facing a dreaded margin call.

Related investing topics

What's the difference between margin trading and short selling?

There are some similarities between margin trading and short selling since both involve additional risks. However, the mechanics of short selling are much different from margin trading.

Short selling means borrowing shares from your brokerage with the intent of buying them back at a lower price. That strategy works when the share price falls, but it can easily backfire. If the stock goes up, you lose money, and, unlike owning a stock, your losses are theoretically unlimited.

In this sense, short selling is even riskier than margin trading because you can be on the hook for an unlimited amount of money. With margin trading, you're only at risk of losing what you've invested and borrowed. Like margin trading, short selling generally requires traders to put up collateral, and a short seller can also be subject to a margin call forcing them to close out their bet.

What margin trading does have in common with short selling is that it should only be considered by very experienced investors who fully recognize the risks. Even then, those investors who want to use them should carefully limit their total exposure so that, when the market moves against them, it doesn't jeopardize the rest of their financial position.

While margin trading can be advantageous at times, overall the risks of borrowing from your brokerage outweigh the benefits.