Business valuation is an educated guess at what an entire business would sell for on the open market. It doesn't matter if you're an income investor seeking dividend yields to provide cash in retirement, a venture capital-level high-growth investor, or a traditional value investor focusing on out-of-favor stocks. If you ignore business valuation, you do so at your peril.

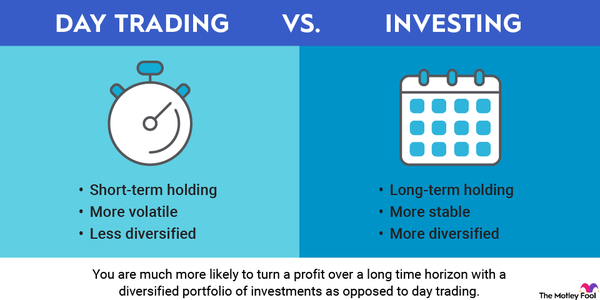

When we buy stocks, our shares represent fractions of a business. Over the short term, stock price movements can seem random because they're driven more by emotion. But, over the long term, stock prices are driven by the compounding value of the business that the stock represents.

Let's go over what business valuation is and how to calculate it.

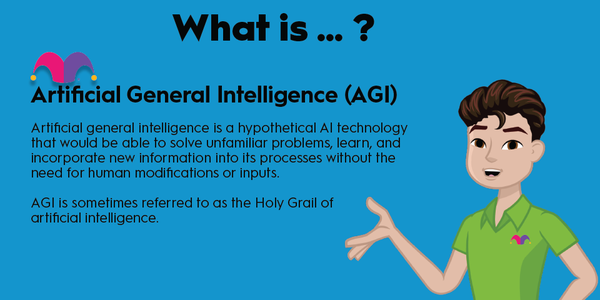

What is business valuation?

Business valuation is the process of estimating what it would cost an independent buyer to purchase the entire business. This means estimating what the future earnings of the business are worth to the buyer, comparing similar business sales, or estimating the value of the business if the assets were sold off piecemeal.

Before proceeding, here's a common saying pertinent to investing: "Business valuation is like the Hubble telescope. Move it an inch and you're in a totally different galaxy."

No matter which of the techniques described below you use, it's important to remember there's no perfect valuation method. Business valuation can be easily influenced by our innate biases. As with any model, GIGO (garbage in, garbage out) applies.

Estimating business value is important for determining whether your purchase will have a margin of safety. Suppose you buy a high-growth stock for $50/share and it's only worth $40/share. (This price is often referred to as the business's intrinsic value.) You don't have room for error.

On the other hand, if you buy a stock worth $100/share for $50/share, it's already trading so low that it is relatively unlikely that bad news will crush your pick. Investors who focus on stocks with a high margin of safety and wait for the stock price to revert to its intrinsic value are called value investors.

Methods of business valuation

Let's walk through the most popular valuation techniques and discuss the strengths and weaknesses of each.

Market cap

Market cap is equal to the current price of the stock multiplied by the number of shares. It tells you the amount it would currently take to purchase the whole business.

Many analysts prefer to adjust the market cap number to get enterprise value (EV), which is the market cap plus total debt minus cash. Enterprise value is a more accurate representation of what it would cost to purchase the business because it includes cash the buyer would receive and debts that they would be liable to pay.

Discounted cash flow

The most common valuation method for professional investment bankers and research analysts is the discounted cash flow (DCF) model. This model projects future cash flows that the business will earn and then discounts them back to a present value.

The first part should be intuitive. The value of a business is equal to the future earnings that it generates for owners. The problem is that money is worth more to us now than it is in the future.

Money that we have now can be invested and compound to a much higher amount in the future. We use a discount rate in the model to give less value to the cash flow that is projected to occur further into the future.

The DCF is the valuation method most ripe for abuse. As you can imagine, it is easy to estimate far higher growth than a business is truly capable of or use a discount rate that is lower than it should be. Each change to the model's inputs includes the opportunity to create a worse intrinsic value calculation.

Comparables

Comparables is another popular valuation method. You compare to the subject business either what comparable companies currently trade for on the stock market or what they have sold for in recent mergers or acquisitions.

The first step is to identify an industry standard price multiple that you can use for comparison. Here are some of the most common multiples:

- Price/Earnings: The P/E is equal to the current stock price divided by the current earnings per share (EPS). This multiple is commonly used as a back-of-the-envelope comparison for stocks with strong earnings power.

- EV/EBITDA: The EV/EBITDA ratio is used to compare companies that have different capital structures because EBITDA, which stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, doesn't include capital costs.

- Price/Sales: The P/S ratio is used for high-growth companies that are spending so much money on growth that they don't have earnings to speak of.

- Price/Book: Book value is equal to the business's assets minus liabilities. It is also called shareholder's equity. Price/book is used for asset-intensive business such as real estate investment trusts (REITs) or banks.

Once you determine which multiple to use, gather the multiples of comparable businesses and find the average. That average can be applied to the subject stock to find an intrinsic value.

For example, let's say you want to value a high-growth stock. You would pick three businesses in the same industry growing at similar rates and find their average P/S ratio. Multiply that number by the subject's sales, and you have an estimated market cap.

Comparable analysis may not seem as scientific as a full-blown DCF spreadsheet, but for many investors it is a more useful analysis. Negotiation between businesses and buyers are usually done with multiple analyses. While DCFs can be easily manipulated, the multiple of every comparable business can't be.

Liquidation value

Liquidation value is typically only used for failing asset-heavy businesses. It is the value to an investor if every debt was paid off and every asset sold in a fire sale. To start the analysis, the value of each asset is adjusted to account for the price it could fetch in a sale:

- Cash: Cash is generally given 100% of its balance sheet value for obvious reasons.

- Accounts Receivable (ARs): ARs are often discounted by as much as 50% to 80%. It takes time and money to track down customers. Most buyers simply sell the ARs to a collection agency for a fraction of their balance sheet value.

- Inventory: If inventory is given any value, it's only 10% of the balance sheet amount. It's notoriously difficult to sell the inventory of a failing business for anything close to market price.

- Property, Plant, & Equipment (PPE): PPE values need to be determined on a case-by-case basis. A forklift that crashed into a wall is worth far less than its balance sheet value, while a building that was purchased 40 years ago and has been fully depreciated is worth far more.

After finding an adjusted asset value, subtract the value of all liabilities. The result is the liquidation value of the business.

Related Investing Topics

Valuation should be simple

While Warren Buffett has written about the virtues of the DCF model, his longtime business partner, Charlie Munger, once remarked that he doesn't think he's ever actually seen Buffett do one. The more complicated a valuation technique is, the more likely it is to experience the GIGO problem.