Tax-equivalent yield is a way to compare the returns of a tax-exempt bond to a fully taxable bond. Some fixed-income securities, like municipal bonds and U.S. Treasuries, provide tax advantages but typically offer lower yields than fully taxable securities, like corporate bonds. Investors should use the tax-equivalent yield to determine whether or not a tax-exempt bond is a good investment for their portfolio.

What is tax-equivalent yield?

What is tax-equivalent yield?

Tax-equivalent yield produces the yield that a fixed-income investment would have to offer to produce the same returns if it were fully taxable. That number will differ from person to person since each individual can have different federal, state, and local tax rates.

Tax-equivalent yield gives investors a framework to evaluate two bonds with different tax treatments side by side. However, it shouldn't be the only factor in an investment decision. The metric cannot account for the level of risk associated with a security. Riskier securities should have higher tax-equivalent yields than safer securities.

Tax treatments

Tax treatment of different types of bonds

Different types of bonds receive different tax treatments. That's why you need to use tax-equivalent yield to compare them.

- U.S. Treasury bonds are exempt from state and local taxes. You still owe federal income tax on the interest paid.

- Municipal bonds, or munis, issued by your home state or city, are typically exempt from federal, state, and local taxes. They may be subject to the alternative minimum tax.

- Out-of-state municipal bonds are exempt from federal income tax, but you'll owe state and local tax and, potentially, the alternative minimum tax.

- Corporate bonds are fully subject to income tax at all government levels.

Note that you'll always owe taxes on any capital gains from your fixed-income investments.

Tax-equivalent yield factors

Tax-equivalent yield factors

There are just two factors that affect tax-equivalent yield.

The first factor is your marginal tax rates for federal, state, and local income. This is the tax you'll pay on your next dollar of income, and it will differ from person to person. So, someone living in a high-tax state like California or Hawaii could have a higher tax-equivalent yield on Treasuries than someone in a state without an income tax.

The other factor involves tax exemptions for the security. Treasuries, in-state munis, and out-of-state munis all have different tax treatments, and not all municipal bonds will receive federal tax exemption.

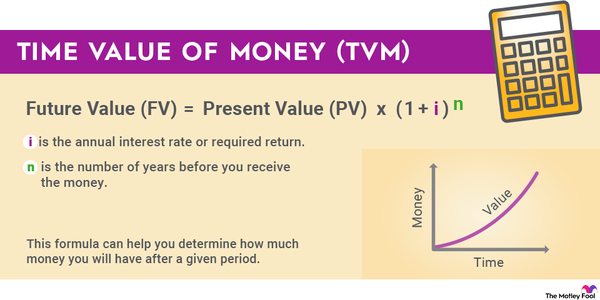

With those two pieces of information, calculating the tax-equivalent yield is straightforward. You take the yield offered by the security and divide it by 1 minus your marginal tax rate.

In other words:

Tax equivalent yield = yield ÷ (1 – marginal tax rate)

Related investing topics

Should you buy them?

Should you buy tax-exempt bonds?

Tax-exempt bonds could be a good investment for your portfolio, but you need to consider a few things.

First, you need to determine alternative investments. If you're considering short-term Treasuries (exempt from state and local taxes) vs. a high-yield savings account, you might be able to get a much better tax-equivalent yield in some environments regardless of your tax bracket. But if you're comparing a local municipal bond to a corporate bond, it's unlikely you'll get a higher tax-equivalent yield unless you have a high income.

It's also important to be able to assess the risk of your investment options. Government bonds are generally considered less risky than many corporate bonds. A government bond should theoretically produce a lower tax equivalent yield than a corporate bond that faces higher risk levels.

You should also be aware of what kind of account you're investing in. If you plan to use funds from an IRA or other tax-advantaged retirement account, the tax-exempt status of government bonds won't benefit you. Earnings inside an IRA are already exempt from taxation. That doesn't necessarily make them bad investments for your retirement accounts; it simply nullifies the tax advantages compared to taxable securities.

When you factor in all those considerations, the choice between tax-exempt and fully taxed bonds will differ widely from person to person.