What is it?

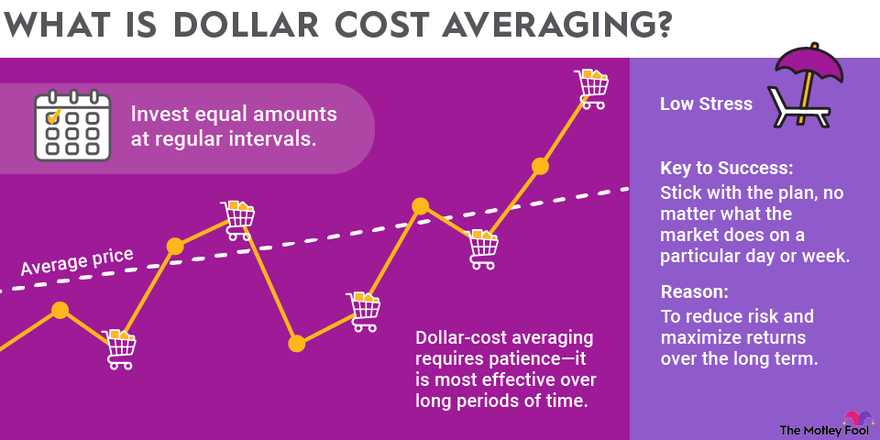

Buying stocks can be stressful. Buy too soon and you risk regret if the price drops. But if you wait and the price goes up, you feel like you missed out on a deal. That's where dollar-cost averaging comes into play.

Dollar-cost averaging is a strategy that tries to minimize those risks by building your position over time. When you dollar-cost average, you invest equal dollar amounts in a security at regular intervals. Rather than attempting to time the market, you buy in at a range of different prices.

Like with most investment strategies, dollar-cost averaging is not for everyone, and there are times it works better than others. But it can be a powerful tool for removing some of the emotional barriers to investing. Here's a look at how dollar-cost averaging works and the best ways to use the strategy.

When you dollar-cost average, you break your investment into pieces and put a portion of your money into the stock market at equal time intervals instead of putting all of it into the market at once.

Fractional Shares

For example, say you have identified FoolishCorp. as an attractive investment and want to buy $10,000 worth of its stock. But you've noticed the stock price tends to move up and down a lot, and you are not sure if the price you'd pay now is the best you'll see or if it will drop in the days and weeks to come. Instead of buying $10,000 worth right now, you could instead buy $2,000 per month for five months.

The strategy doesn't have to be limited to one security or a fixed amount of time. In fact, those with 401(k) plans and other retirement accounts may already be dollar-cost averaging through those plans by buying a fixed amount of a number of mutual funds and stocks every payday regardless of whether the market is at an all-time high or in the middle of a sell-off.

Why it works

Why dollar-cost averaging works

Dollar-cost averaging works because it removes some of the emotional stress that comes with investing. By committing to a set schedule, you don't have to worry about whether a stock is about to move higher or lower.

To go back to the example of FoolishCorp., let's assume you buy $2,000 worth of its stock for five consecutive months. Let's also say that, on the days you buy, the stock is trading at $50, $40, $20, $40, and $50, respectively. Over the course of those five months, the stock price ended up where it started, but it took a wild ride in the meantime.

Here's how the purchases would look:

| Month | Investment Amount | Price per Share | Number of Shares Purchased |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $2,000 | $50 | 40 |

| 2 | $2,000 | $40 | 50 |

| 3 | $2,000 | $20 | 100 |

| 4 | $2,000 | $40 | 50 |

| 5 | $2,000 | $50 | 40 |

| Total | $10,000 | $35.71 (average) | 280 |

Note that in this example, if you had bought the entire $10,000 stake on day one, you would have only gotten 200 shares. So, by dollar-cost averaging, you were able to buy more shares with your money. Obviously, that's not always the case. If the stock price goes straight up, you would get fewer shares.

You can use this strategy for any investment, whether it's a stock, mutual fund, or exchange-traded fund (ETF). Generally speaking, dollar-cost averaging works best in bear markets and with securities that have dramatic price swings up and down. It is those times, and those types of investments, where reducing investor anxiety and fear of missing out tend to be the most important.

Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF)

If you do dollar-cost average, beware of hindsight. It is easy to doubt yourself if you spend too much time looking backward. If a stock goes straight up from your starting point, clearly it would have been better to buy as much as possible on day one. Or, taking the FoolishCorp example, it would have been better to buy the full $10,000 in month three. But the whole point of this strategy is we have no way of knowing how a stock is going to move.

If you have a crystal ball, use it. But for the rest of us, dollar-cost averaging is a better strategy than trying to time the market.

When's the best day to do it?

When's the best day to dollar-cost average?

There are a lot of so-called investment experts who claim there are certain days to deploy money due to payroll schedules and mutual fund flows. Don't believe it. If there was a magical formula for picking the right day each month to buy stocks, we'd all just buy then and not have to figure out other strategies.

However, when you dollar-cost average is important. Specifically, you must make a consistent plan and stick to it. A lot of the benefit of the strategy is that, by breaking the investment into chunks, you can avoid worrying over when to buy in and avoid trying to time the market. Therefore, it's important that, once you pick a date, you stick to it no matter what happens.

For example, say you commit to buy $1,000 worth of an index fund on the first day of every month. But, in month four, you notice that stocks have been up the whole week leading up to the first day of the month. It might be tempting to assume that a sell-off is inevitable any day, so you hold off buying on the first day of the month in the hope of getting a better price in the days that follow. If you do that, you eliminate a lot of the rationale behind trying dollar-cost averaging.

The downside

What's the downside of dollar-cost averaging?

There are a few things to consider before dollar-cost averaging. For one, it's impossible to predict whether stock prices will go up or down on any particular day, week, or even year. But there is a century's worth of data showing us that markets do rise over time.

If you park most of your money out of the market and only buy in a bit at a time, you avoid short-term volatility. But that also means a portion of your cash is on the sidelines and not working to build your net worth.

That's a particularly big risk if you are focused on dividend stocks and other income-generating investments. Except in extreme cases, dividend payers continue distributions in good markets and bad. If you use dollar-cost averaging to slowly build a position in a dividend stock, you miss out on getting dividends on the portion of your cash you haven't yet invested.

Finally, note that any investment strategy is only as good as the stocks you pick. Dollar-cost averaging can help ease apprehension and is better than trying to time the markets, but it is no substitute for finding quality companies to invest in.

Is it for you?

Is dollar-cost averaging right for you?

Dollar-cost averaging is beneficial because it can reduce investor anxiety, help avoid trying to time the market, and can provide a predictable, regimented way to continuously grow your nest egg. If that's of interest to you, there are a few simple steps to follow:

- Decide how much money you want to invest. It could be a one-time windfall you want to put in the market or it could be a set amount you intend to contribute on a regular schedule indefinitely.

- Decide how often you want to invest. With trading commissions all but gone, it can be daily, weekly, monthly, or any interval you want.

- Decide how many periods you want to split the investment over. Again, it could be a few times, or it could be the start of a permanent routine.

- Decide the dollar amount invested at each interval. If it's a lump sum, divide the amount by the number of periods. If it is an indefinite investment plan, budget how much you can reliably afford.

- Stick with the plan, no matter what markets do on a particular day or week.

There is no one right way to invest. But if you're an investor looking to increase your net worth but worried you might be tempted to time the market, or you're dedicated to adding a little bit each month regardless of recent stock returns, dollar-cost averaging can be an effective way to build your portfolio.