In just over two months, the most important Social Security event of the year will unfold: The Bureau of Labor Statistics will release inflation data from September, allowing the Social Security Administration to announce the 2019 annual cost-of-living adjustment, or COLA. Think of COLA as nothing the "raise" Social Security recipients receive from one year to the next.

Waiting on mid-October's COLA announcement

The annual release of Social Security's COLA takes a lot of precedence, given that, according to data from the Social Security Administration, 62% of retirees are reliant on the program to provide at least half of their monthly income. Even though we're only talking about an average retired worker benefit of $1,413.37 a month, as of June 2018, that's more than enough to keep an estimated 15 million retired workers above the federal poverty line.

Image source: Getty Images.

Ideally, beneficiaries want the biggest raise they can get to help offset the rising costs of housing, medical care, food, and other expenditures. But in recent years, COLA has been anemic. In 2010, 2011, and 2016, there was no cost-of-living adjustment (i.e., deflation occurred), and in 2017 it was a meager 0.3% -- the smallest increase on record over more than four decades. However, that could change in 2019.

Since the mid-1970s, when COLA was first introduced on an inflation-indexed basis, rather than having Congress just make whimsical guesses, the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) has been the program's inflationary tether. Through June, based on the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the CPI-W had risen by an unadjusted 3.1% over the trailing-12-month period. Hypothetically speaking, a 3.1% raise in 2019 would be the largest increase for beneficiaries since 2012, when COLA rose 3.6%.

Keep your eyes on the skies

But what's even more interesting about next year's COLA is how influential energy prices are turning out to be. According to the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), a very similar measure to the CPI-W, energy commodities, such as gasoline and fuel oil, are up an aggregate of 24.3% on an unadjusted 12-month basis.

In even simpler terms, rising crude oil prices have increased prices at the pump, which, in turn, has helped push the CPI-U and CPI-W notably higher. Don't get me wrong: Shelter, transportation services, and medical care expenditures are up as well (mostly in the mid-2% to mid-3% range) on a trailing-12-month basis, but this is predominantly a crude-driven inflation.

Image source: Getty Images.

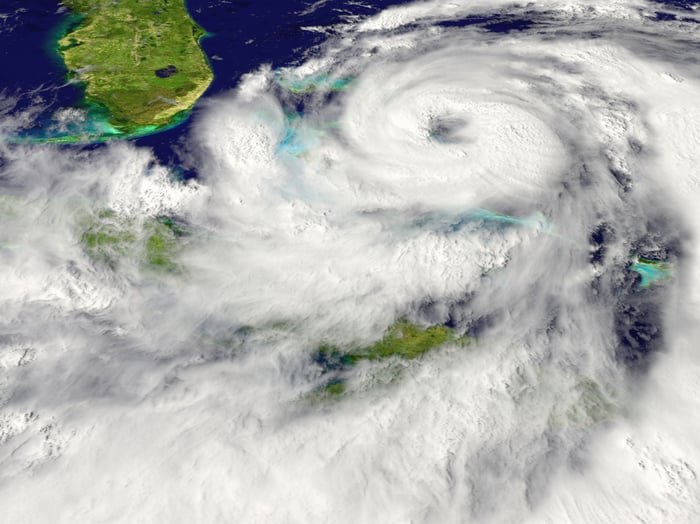

Yet what Social Security recipients may not remember from last year is that two major hurricanes, Harvey and Irma, disrupted production and/or refining of petroleum byproducts in the U.S., which substantially increased inflation in the energy sector. Since Social Security only considers and compares the average third-quarter CPI-W reading (July through September) from the previous year, and the average third-quarter CPI-W reading from the current year, when calculating COLA, these two hurricanes tacked on what I'd estimate was an extra 0.5% of COLA for the current year (COLA was 2% in 2018). Had these hurricanes not disrupted refining and production in the Gulf of Mexico, COLA would probably have been a more pedestrian 1.5% this year.

What Social Security recipients will want to monitor over the next two months is the severity of this year's hurricane season. Although crude prices have been strong pretty much all year, which would suggest a healthy cost-of-living adjustment increase no matter what, another hurricane season like we had last year, in which production and refining are disrupted, could lead to an even more robust COLA. While I'm not saying cross your fingers and hope for a hurricane, because natural disasters aren't a good thing, they do have the ability to be a needle-mover for Social Security beneficiaries via a bump in COLA.

As a reminder, a COLA of 3.7% or higher would represent the biggest raise in a decade, and it's not out of reach if this hurricane season is particularly active.

A big COLA doesn't resolve Social Security's inflation issues

However, as we've examined before, Social Security's inflation issue means even a COLA of 3%-plus isn't going to put seniors on solid footing.

An analysis published by The Senior Citizens League finds that the purchasing power of Social Security dollars has declined by 34% since the year 2000, through January 2018. Though you might think that the CPI-W does a decent job of measuring the inflation that retired workers are facing, it's actually mirroring the spending habits of working-age urban and clerical workers, who tend to have markedly different expenditures than seniors. As a result, medical care and housing don't get nearly the representation as a percentage of total expenditures as they should and, thus, seniors continue to receive an inadequate raise more years than not.

Image source: Getty Images.

Perhaps the saddest part of all is that there's no simple fix to right the ship. Should Democrats implement their proposed inflationary measure, the Consumer Price Index for the Elderly (CPI-E), which takes into account the spending habits of households with people aged 62 and over, seniors, who comprise a majority of Social Security beneficiaries, would get a more accurate annual COLA. But it would also cost the program more over the long-term (75-year) forecast. And in case you needed a reminder, Social Security is already staring down a $13.2 trillion cash shortfall between 2034 and 2092.

Conversely, Republicans could turn to the Chained CPI, which is a measure that's currently tethered to federal income tax brackets, deductions, and credits, as a result of the passage of Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in December. The Chained CPI takes into account a buying habit known as substitution bias. This is where consumers trade down from a more expensive good to a similar but more affordable good. Using the Chained CPI could save Social Security money over the long run, but it would also generate even lower annual COLAs.

With Democrats and Republicans at the opposite end of the spectrum in terms of fixing COLA, and neither party willing to work cooperatively with the other, it seems all but a certainty at this point that Social Security dollars will continue to lose purchasing power over time.