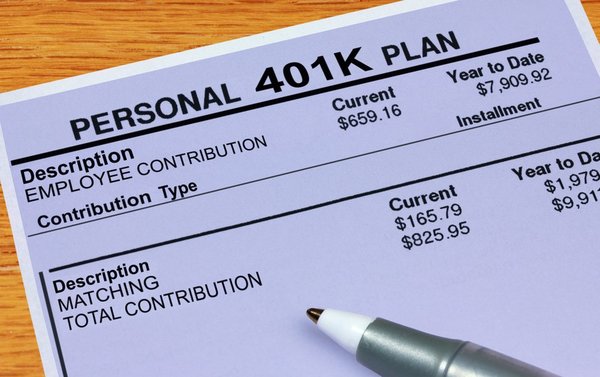

401(k) matching contributions can be a wonderful perk for employees. Under an employer matching program, your employer agrees to contribute money to your 401(k) account, matching what you save from your own paycheck, pre-tax, up to a certain limit. For example, an employer might agree to match 100% of employees' 401(k) contributions up to a maximum 5% of salary.

Matching is a terrific benefit, and more than 90% of employers that offer 401(k) plans provide a company match. However, the money your employer contributes typically isn't yours right away, and you could lose it if you leave your job. In most cases, there is a point at which the funds your employer contributes legally become yours, and that's where vesting comes in.

Here's an example of how powerful an employer match can be: If your salary is $60,000 and you contribute 5%, you save $3,000 per year for retirement. But if your company offers a 50% match, it kicks in a total of $1,500 on top of your contribution, so your account actually receives an annual contribution of $4,500 -- a nice sum that will compound over time to benefit you in retirement.

What does vested mean with a 401(k)?

Here's a very important concept for employees who participate in a 401(k) plan. While you always own the money you contribute from your own paycheck, you typically don't own the employer's matching contribution right away.

The process by which your employer's contributions legally become yours is known as vesting. A few employers offer immediate vesting, meaning that you'll own your entire 401(k) balance at all times. But this isn't the normal approach -- most 401(k) plans vest employer contributions over time.

401(k) vesting schedules

As previously noted, employers can opt for immediate vesting. This means that employees own 100% of their 401(k) accounts at all times -- even their employer contributions. However, this isn't very common. Most employers choose one of the following two other vesting options.

Graded vesting

With a graded vesting schedule, a certain percentage of the employer contributions to your 401(k) vest each year over a set period until you are fully (100%) vested in your account.

If an employer chooses to use a graded vesting schedule, they must vest at least 20% of employer contributions at the end of two years and another 20% annually in subsequent years. The longest a graded vesting schedule can last is six years, at the end of which employees are 100% vested.

As a simplified example, let's say that your employer uses the standard graded vesting schedule, and at the end of your third year, $10,000 of your 401(k) value can be attributed to employer contributions. Since you'd be 40% vested at this point, you would legally own $4,000 of this amount plus whatever portion of your account came from your own elective contributions.

Cliff vesting

With a cliff vesting schedule, your 401(k) will fully vest at a specific time. Unlike with a graded vesting schedule, it doesn't happen gradually -- you'll be exactly 0% vested one day and 100% the next.

If your employer chooses to use cliff vesting, they can set the vesting time at up to three years. If they do this, you immediately become fully vested in your 401(k) account upon the third anniversary of your employment.

It's important to note that these examples show the longest your employer contributions can take to vest. Your employer is allowed to use a faster vesting schedule than these but not a slower one. The vesting schedule for your particular plan should be clearly spelled out in the information your employer provides about its 401(k) plan.

401(k) vesting after termination

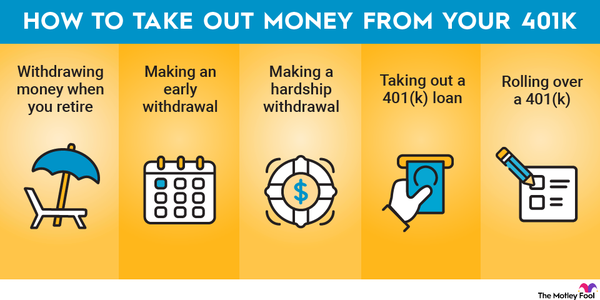

If you leave a job before your 401(k) is fully vested, you'll likely lose the unvested portion of the account. After all, that money isn't legally yours until you've been at your job long enough to satisfy the vesting schedule used by your employer's plan.

When you leave a job before being fully vested, the unvested portion of your account is forfeited and placed in the employer's forfeiture account, where it can then be used to help pay plan administration expenses, reduce employer contributions, or be allocated as additional contributions to plan participants.

401(k) vesting rules, requirements, and regulations

The graded vesting and cliff vesting rules described above are set by the IRS in order to ensure that employers can use vesting to help retain employees while still giving workers ownership of their retirement savings within a reasonable time.

To be clear, the graded vesting and cliff vesting schedules mentioned here show the longest contributions can take to vest. Employers may opt for more generous schedules; for example, an employer could do a graded vesting schedule that allows employees to be 100% vested after three years instead of six. But they couldn't choose to require eight years of service to be fully vested.

Is it ever a good idea to leave a job before you're fully vested?

It may seem silly to leave a job voluntarily before your retirement account is fully vested since you're literally giving up a portion of your retirement account by doing so. However, there are some cases where the financial benefits of switching jobs can outweigh what you're giving up.

Consider this hypothetical example. You have $20,000 in your 401(k) account, but you're not currently vested in $3,000 of it. You get an exciting new job offer that will boost your salary significantly. If you're going to be fully vested in a couple months, it may make sense to wait until you vest before giving notice. But if you're not going to fully vest in the $3,000 for another two years, it may be more prudent to take the higher salary right away. You'll forfeit $3,000, but if your salary adjustment results in more than $3,000 over two years, you win.