401(k)s are among the most popular retirement plans around. This is largely due to the up-front tax breaks they give participants, but you don't get out of paying taxes forever. Your tax bill comes due when you take your money out, and how much you'll owe depends on your age and income when you make the withdrawal.

Below, we'll look at how the government handles taxes on 401(k) contributions, withdrawals, and special situations such as early withdrawals and 401(k) rollovers.

Taxes on 401(k) contributions

The biggest benefit of most 401(k)s is that your contributions are tax-deferred, meaning the government doesn't count this money when determining how much you earned during the year. That lowers your tax bill, sometimes considerably. If it drops you into a lower tax bracket, you will pay a smaller percentage of your income to the government, enabling you to hold on to more of your earnings. Employer-matched funds are also tax-deferred, so you don't have to worry about paying taxes on these right away either.

The government limits how much you can contribute to a 401(k) in a given year because of these tax breaks. In 2024, you can contribute up to $23,000 if you're younger than 50, or $30,500 if you're 50 or older. In 2023, these limits were $22,500 and $30,000, respectively. You don't need to worry about deducting your contributions on your taxes since the tax forms provided by your employer should already indicate how much money you contributed to your 401(k).

There is a special type of 401(k), the Roth 401(k), that the government taxes differently. It uses after-tax dollars, so you pay taxes on your contributions, but your money grows tax-free afterward. Your employer may offer this option instead of, or in addition to, your traditional 401(k). Make sure you understand the differences between the two so you aren't surprised by an unexpected tax bill.

Taxes on 401(k) withdrawals

Your 401(k) distributions are taxed as ordinary income. All that means is the government treats it the same as money you earned from a job. The good news for most people is that incomes typically drop in retirement compared to earlier working years. That means you could end up in a lower tax bracket where you'll pay less of your savings to the government.

Before the passage of the Secure Act 2.0, employer contributions were always pre-tax. But since 2023, employers have had the option of making post-tax contributions. Not all employers offer this option, though.

You'll need to be prepared for taxes when planning for your retirement. You may think you'll need only about $40,000 per year to cover your living expenses in retirement, and you might be right. But if you withdraw that $40,000, you may need to pay taxes on it, leaving less money available to cover your expenses.

If you want to retire for good, you must make sure your retirement planning is thorough enough to plan for both living expenses and any applicable taxes. You can use estimates of your retirement spending and the current tax brackets to get some idea of how much you might owe annually.

What to know about early withdrawals

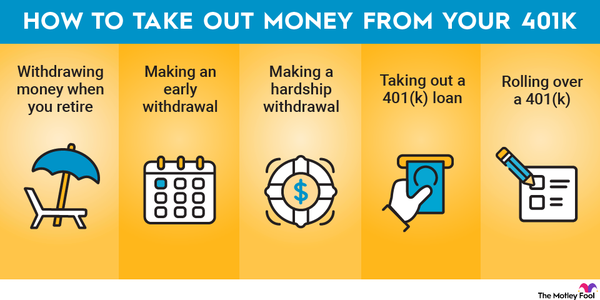

Your 401(k) funds are meant to be your safety net in retirement, so taking money out before retirement isn't a great idea. But if you're in a financial pinch, you may not have another choice. Just know you will be responsible for paying taxes on your withdrawals, even if you're not retired yet. This will raise your tax bill for the year, although how much depends on the size of your withdrawal and how much other income you earn during the year.

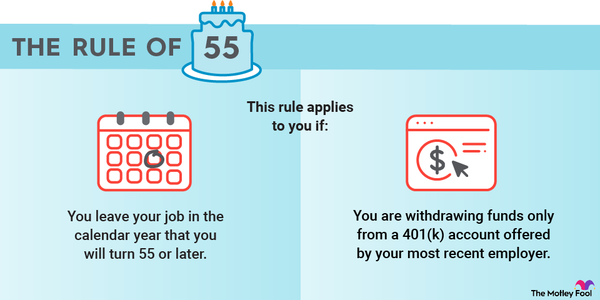

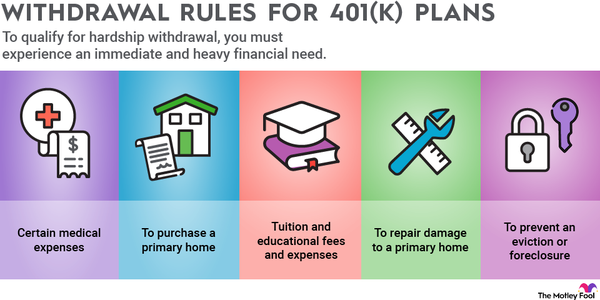

If you're younger than 59 1/2 when you make your 401(k) withdrawal, you'll also pay a 10% early withdrawal penalty unless you qualify for an exception. Exceptions include medical expenses that exceed 7.5% of your adjusted gross income (AGI), a first-home purchase, or becoming permanently disabled, among other life events. Note that these exceptions don't get you out of paying taxes on your withdrawals; they only eliminate the 10% penalty.

Related Retirement Topics

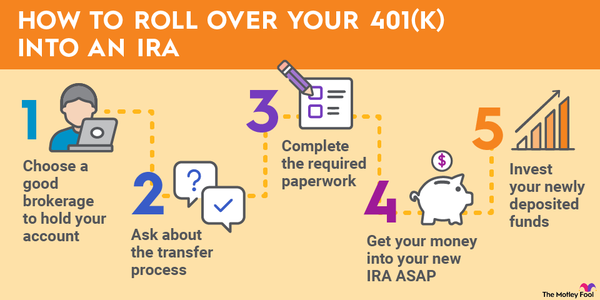

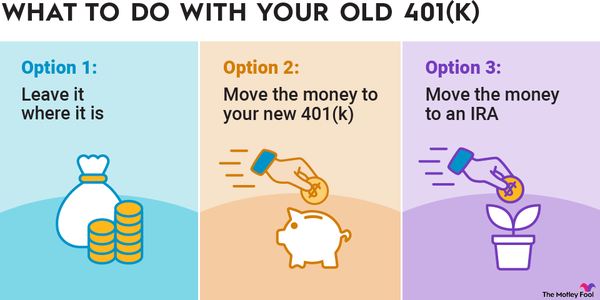

Avoid taxes on your 401(k) rollover

Rolling over a 401(k) to an IRA or a new employer-sponsored retirement account isn't considered a distribution as long as you do it properly. There are two ways you can go about it. The first is called a direct rollover. You provide your 401(k) provider with details about where you'd like your funds transferred, and they will automatically send the money to your new account. You may pay a one-time service fee for doing this. If you're unsure how to get started, talk to your 401(k) plan administrator.

The other option is an indirect rollover. Here you withdraw all of the funds from your 401(k) yourself and then deposit them into your new account. As long as you deposit the funds into the new account within 60 days of the withdrawal, the government won't consider it a distribution. But if you don't deposit the money in time, or you fail to deposit the full amount you withdrew from your 401(k), the government is going to come around asking for its cut.

That's why the direct rollover method is usually considered safer. You don't touch the money at all, so you don't have to worry about owing taxes right now. It is possible to do an indirect rollover without paying taxes as well, but make sure you deposit the new funds right away to avoid any issues.

401(k) tax rules aren't that complicated, but they're too often overlooked. Make sure you understand all of these rules and consider the tax implications before you make a withdrawal. Try to avoid making any withdrawals at all until you're ready to retire, and, even then, take out only as much as you need during a single year. This will help keep your tax bill low, and it will give your savings more time to grow so they'll be worth more in retirement.