Paying taxes on gains from long-term investments can be a major hurdle for investors. Yet the tax law actually gives heirs a huge tax break -- the ability to reset their cost basis -- when they inherit shares of stock or other investments that have increased in value. This tax law lets you wipe out potential capital gains tax liability entirely, which can cut thousands of dollars off your tax bill. Below, we'll go through how to figure your cost basis on inherited stock.

The basis step-up

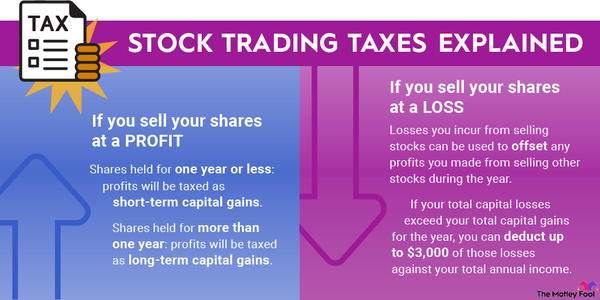

Capital gains taxes are calculated based on the profits after the return of capital (ROC). Investors will have a tax liability when they sell a stock for an amount greater than the ROC basis -- or the cost at which the equity was acquired.

The rules behind the cost basis of inherited stock are simple. Most of the time, you calculate the cost basis for inherited stock by determining the fair market value of the stock on the date that the person in question died. Sometimes, however, the person's estate may choose what's known as the alternate valuation date, which is six months after the date of death. In that case, the inherited cost basis can be much different from the deceased person's cost basis before death.

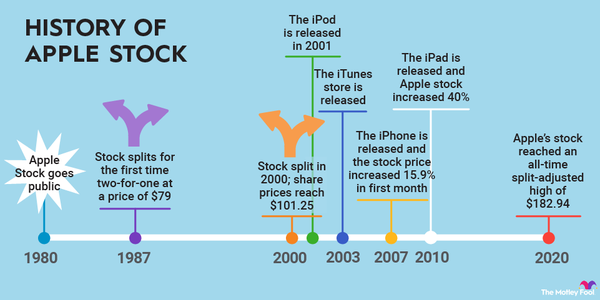

For example, let's say a person purchased Walmart (WMT 0.46%) stock at the beginning of 1980 when it was trading at a split-adjusted price of roughly $0.08 per share. If they sold that holding shortly before death 40 years later, a substantial amount of income tax would be due because of gains the stock had made through the decades. However, if that stock was instead bequeathed to an heir, the cost basis would be reset. It would either reset to the company's share price on the day of the deceased's passing or on the alternative valuation date, depending on what was stipulated by the estate.

The perk here is that decades of stock growth would then not be subject to taxation. As a result, the heir would pay a much smaller tax bill on any shares sold at a profit. Securities sold or gifted before the owner's death are subject to taxes based on the original cost basis. Inherited stocks, on the other hand, will often be subject to lower taxes because the cost-basis step-up reduces the amount of capital gains.

By the same token, of course, people who inherit stock cannot claim any losses that occur before the original owner's death. Unfortunately, even if the value of stock plunges on the day of the deceased person's death, the heirs won't be able to use those losses to offset gains from their other investments.

Reasoning behind the cost basis step-up

The IRS began taxing estates with the passage of the 1916 Revenue Act. This change to the tax code was primarily meant to help fund World War I by supplementing the funds generated from income tax. However, in addition to creating a new tax to generate more revenue, lawmakers also saw a practical benefit to allowing for a stepped-up basis on inherited wealth.

As anyone who has invested for a long time can attest, keeping track of the cost basis for your stocks can be an ongoing nightmare. Keeping records of every purchase and reinvestment over time is a monumental task. When you have to rely on someone else's records dating back to before you even took ownership of the inherited stock, that task can become almost impossible. In addition, because assets in a person's estate are potentially subject to estate taxes, the basis step-up eliminates the possibility of double taxation.

Figuring out the basis

If a substantial time has passed since you inherited the stock, you'll need to find prices for the shares at the date of death. Fortunately, those prices are readily available from financial news sources and from company investor relations departments. If a tax return was filed for the estate and an alternative valuation date was chosen, those values should be used as the stepped-up basis instead.

In addition, it's important to note that if you've enrolled in an automatic dividend reinvestment plan (available via most major brokerages), you may have purchased additional shares after you inherited them. It's crucial to understand that the cost basis of the inherited shares is separate from the cost basis of the newer shares. If you fail to account properly for both sets of shares, you can end up paying more in capital gains taxes than necessary.

The cost-basis calculation should be the same whether a person inherits stock through a revocable trust or a will. The same holds true for stocks inherited through a brokerage.

Finally, keep in mind that the step-up rules apply only to property that was legally included in the deceased person's estate at death. Gifts of stock that someone gave you while they were still living don't get a step-up. Trusts on your behalf that became irrevocable prior to the death of the creator often won't get favorable treatment either.

Nevertheless, in most situations involving inherited stock, the basis step-up rules make things a lot simpler and less costly for heirs. Just knowing the rule and using it correctly can save you thousands in unnecessary taxes.

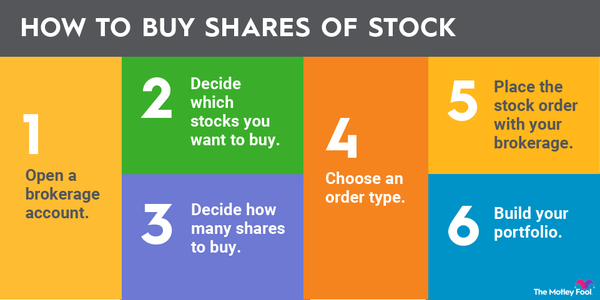

Related investing topics

Determining valuation basis for estate taxes

If the value of an estate is large enough to qualify for federal estate taxes, then stocks that are included will be taxed as part of the overall value of the estate. The federal estate tax threshold was raised to $11.7 million per individual and $23.4 million per married couple in 2021. Additionally, the federal estate tax threshold for individuals will be raised to $12.06 million in 2022, and the threshold for married couples will be raised to $24.12 million. This means that stocks won't be taxed as part of an inheritance provided the overall value of the estate is below those levels.

The vast majority of estates are valued at levels that do not trigger federal estate taxes. However, a valuation basis for included stocks must be used to determine if estates exceed the threshold. Just as with inheriting stocks, the valuation basis of stocks and other equities in the estate is set by their market value on the day of the deceased's passing or the alternate valuation date. While states also have their own estate tax and inheritance tax laws, the standards for determining cost basis are the same.