How and Why to Value a Business

It’s a good idea to determine the value of your business once a year or so. It helps with retirement planning and allows you to quickly respond to any offers. And, if you’re ever looking for venture capital financing, you’ll have a head start at calculating the pre-money valuation.

There are many ways to find the valuation of a company. We’ll go over industry standard multiples and a discounted cash flow model, and then we’ll perform an asset valuation.

Each of these models is simple enough that you can perform the valuation on your own business. We’ll use the financials of Target Corp. to work through the models. (My wife reads these articles and hasn’t been able to go to the store very often during the pandemic. In her mind, any Target exposure is good exposure.)

1. Multiple

Multiple analysis is the most common way to value small businesses. If you’re looking to sell your business and talk to a business broker, you’ll often start with a rule-of-thumb valuation of 2x revenue or 5x cash flow.

The key is to figure out what small businesses are selling for in your industry. A good broker will know this information. You may also be able to talk to your business banker for information. Banks often keep databases for underwriting business acquisition loans.

The multiple for your industry should make intuitive sense based on whatever business metrics you focus on. Capital-intensive businesses will often be a multiple of assets, and non-capital-intensive businesses will be a multiple of some form of cash flow or revenue. The most complicated you will get is something like 3x operating income plus inventory.

Once you figure out what multiple to use, apply it to your business financials, and you have the market value of your business.

Let’s take a look at how we would do this with Target.

Target’s valuation is between $61.7 billion and $87.9 billion. Image source: Author

I found the price to sales (P/S), price to book (P/B), and price to earnings (P/E) multiples for three of Target’s biggest competitors. The competitors’ choices aren’t 100% perfect, but it would be logical for Target to sell for approximately the same amount.

When you apply the average multiple to Target’s 2020 financials, you get a valuation between $61.7 billion (P/S) and $87.9 billion (P/E). The P/S valuation is significantly lower than the other two, so there may be a good argument to be made that it’s not as relevant.

Each of these companies is a capital- and cost-intensive retailer, and P/S valuations are traditionally geared more toward fast-growing technology companies with low capital requirements.

Target’s current market value is around $81 billion, so we were able to get pretty close with this valuation.

2. Discounted cash flow

I am convinced that discounted cash flow (DCF) models were invented to keep professors employed. I must have had seven finance classes in college that looked at DCFs or time value of money in a different way.

In the real world, DCFs are nice to get a good idea about what the business is worth to you, which is great for looking at opportunity cost. But, in the real world, your business is only worth what someone will pay for it, and business buyers may not be overly concerned with your spreadsheets.

In a DCF model, we use projected financials to figure out what a business will earn in the future and then discount those values back to the present. Future cash is worth less than present cash because cash you have now can be invested to earn a return.

Those professors I was talking about have incredibly intense formulas to derive the discount rate, but that is mostly a waste of time. To keep it simple, we will use 10% as the discount rate.

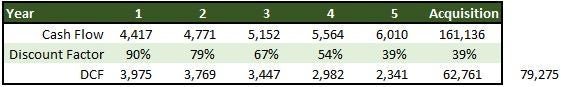

Target’s value with the DCF model is just south of $80 billion. Image source: Author

At first glance, the DCF seems reasonable. The sum of discounted cash flows is equal to a bit less than $80 billion, which is in line with what we got with the first method. (Spoiler alert: That’s because I just made it work.)

The reason DCFs aren’t widely used is because they’re so easy to manipulate. In the table above, I used a 10% discount rate, an 8% annual growth projection, and the P/E multiple we found above for a projected acquisition in year five. I actually started with a lower multiple and growth projection, and the total value was about $20 billion less, so I fiddled with the numbers to get to around $80 billion.

If you can argue it, you can make just about any value work in a DCF. Somewhere out there is a Target lover (possibly my wife) who thinks that within two years all Walmart shoppers will spontaneously start shopping at Target and cash flow will double each year. The value she could justify with that assumption would be far higher than anything else we would come up with in a “reasonable” analysis.

This is dangerous ground for you as a business owner. You have to be optimistic about the future of your business to keep moving forward and sell customers, investors, vendors, and even employees on your prospects. There is a place for that optimism, but if it’s applied to a valuation, you could be missing out on good deals.

3. Asset / Liquidation

I have the most experience with the asset valuation method. As a loan officer and underwriter, I’ve worked on a ton of business acquisition deals. From the bank’s perspective, multiple and DCF analysis have a place in the writeup, but they’re useless for credit purposes. What we needed was assets.

If we lent you $500,000 to buy a business that only had $100,000 in assets, there would not be enough collateral for the loan. So we’d have to get a second lien on your house, and if that wasn’t enough, we’d use a Small Business Administration (SBA) guarantee as a backstop.

There are two ways to approach asset valuation: from a purchase perspective and from a liquidation perspective. When you’re buying or selling a business, it makes sense to give at least full credit to most assets.

You should expect to receive all accounts receivable and sell all inventory. If a business has failed, and it’s going to liquidate (this is the bank perspective), the inventory will probably only sell for pennies on the dollar, and the ARs will have to be sold to collection companies.

Let’s look at how we’d value Target from both perspectives.

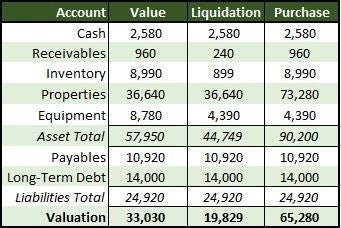

Target’s asset value is less than its DCF or multiple value. Image source: Author

The Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) require us to list assets on the balance sheet at their cost. For liquidation value, we don’t care about the cost. We only care about what we could get for the asset now in a fire sale. For purchase value, we care about replacement cost, or what the cost would be to replace the assets now.

All of the liquidation value adjustments are downward. Receivables get 25% of their value since they will be sold off to a collection agency. Inventory gets only 10%.

One bank where I worked started to give inventory zero value after a frustrating summer trying to sell 8,000 branded fish T-shirts that no one would ever want. Equipment is discounted by a flat 50% in this example. In real life, you can get a desktop appraisal of equipment for a few hundred dollars and use that amount.

Cash and properties stayed steady. In all likelihood, there is no exchange of cash in a small business sale. The selling business would just distribute it all to the owner before the sale. Properties retain their value over time, and, depending on location, typically increase in value. To be conservative, we kept the book value in this example.

When you’re selling your business, you want full value for the real estate. We used double the value for simplicity, but in the real world you would get an appraisal.

Notice that the asset value, even when using the more aggressive purchase methodology, is substantially less than the other two valuations. This is because of goodwill, which is the intangible value of the business. In accounting, you back into a goodwill number by subtracting the asset value from the purchase price.

For Target, this value comes from its brand and from loyalty to the business earned from people using its app, its credit card, and simply enjoying the in-store ambiance.

It’s a lot more rare to be able to sell a buyer on intangible value in a small business. Small businesses are more a reflection of their owner. If some random person came in and took over your business tomorrow and kept the brand name, would it be worth the same? Of course not because they wouldn’t have years of experience learning the industry and working with customers.

This is why you’ll often see small business sales come in at around the adjusted asset value and why multiples for small businesses are far lower than they are for massive billion-dollar corporations.

What you can get

While you can use each of the models to figure out what your business is worth, in reality it’s only worth what you can get from a buyer. Keep that in mind when you’re doing the analysis. And when you want to buy a business, it helps in negotiations to think from the current owner’s perspective.

Alert: our top-rated cash back card now has 0% intro APR until 2025

This credit card is not just good – it’s so exceptional that our experts use it personally. It features a lengthy 0% intro APR period, a cash back rate of up to 5%, and all somehow for no annual fee! Click here to read our full review for free and apply in just 2 minutes.

Our Research Expert

We're firm believers in the Golden Rule, which is why editorial opinions are ours alone and have not been previously reviewed, approved, or endorsed by included advertisers. The Ascent does not cover all offers on the market. Editorial content from The Ascent is separate from The Motley Fool editorial content and is created by a different analyst team.

Related Articles

View All Articles