Lululemon logo from Lucky Luon headband. Image by Jason Michael under Creative Commons license.

One of the most difficult exercises in investing can be trying to determine if a formerly successful stock, having suffered an acute setback, has transitioned into a compelling value investment. Surely lululemon athletica's (LULU 1.31%) shares warrant some inquiry in this vein. After all, despite a rough 2013 plagued by consumer missteps and supply chain issues, and despite reduced earnings expectations for 2014, the company is still profitable, with a very strong financial position, and a new CEO who is aiming to push international expansion. So why is the market so pessimistic on these shares?

A cautionary tale for management teams: don't overplay your strengths

Lululemon became a public company in 2007 and has enjoyed eight years of growth, propelled by its yoga apparel, which sells at a premium to competitors' offerings. Lululemon's pricing power has enabled it to enjoy a higher gross margin than its peers: Its annual 53% annual gross margin is well ahead of competitors such as Nike, Gap, and Columbia Sportswear, which posted recent annual gross margins of 44%, 39%, and 44%, respectively.

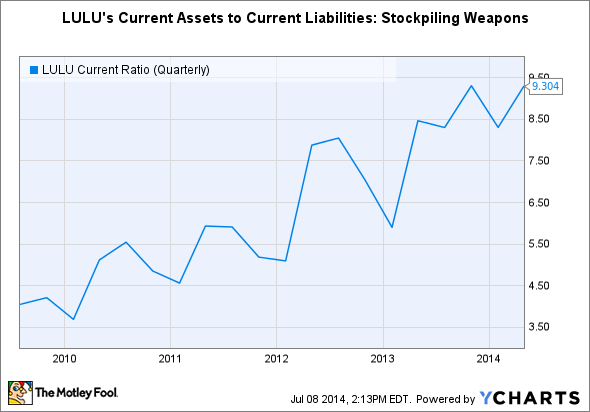

The relative comfort of its margins has enabled Lululemon to produce attractive earnings and cash flow. The company has an extremely strong balance sheet, with virtually zero debt and ample cash on hand. Just how strong is its balance sheet? Too strong, it turns out. Here's a chart of Lululemon's current ratio trend over the last five years. The "current ratio" is defined simply as current assets divided by current liabilities:

LULU Current Ratio (Quarterly) data by YCharts.

The idea that Lululemon can pay for its current obligations (due within one year) with current assets (i.e., cash and inventory) more than nine times over seems praiseworthy, doesn't it?

On the contrary, a high current ratio can reveal a company that doesn't invest its resources properly. A benchmark current ratio across industries is 1:0, meaning that at minimum, most corporations keep one dollar in current assets on hand for every dollar of current liabilities. A ratio of less than 1.0 is undesirable, as a company may not have enough ready money in its coffers to pay upcoming bills.

As a rule of thumb, a current ratio is optimal somewhere between 1.0 and 2.0 -- too much above 2.0 or 3.0 is a potential yellow flag that management isn't getting an appropriate return on the profits it converts to cash, or worse, that a company may not be investing in future growth. For Lululemon, this appears to be the case. The steep chart above demonstrates that as each year has concluded, Lululemon has stockpiled its cash.

Yet outside of this cash and inventory for its stores, the company doesn't have much in the way of assets to show for all its profits. Property and equipment at May 4, 2014 (Lululemon's fiscal 2014 first quarter-end) is only $271.3 million, net of accumulated depreciation, with the greatest part of this in land, office buildings, and leasehold improvements for stores.

Computer and software equipment is listed at only $107.8 million. This amount would include point-of-sale equipment in the company's stores, and software and computers at the company's headquarters and distribution centers. Compared to the size of the company's revenues, it seems a rather lean number. In addition, a note to the company's 2014 annual report relays that capitalized expenses for "software developed for internal use" is only $1.6 million.

This $1.6 million, a mere 1/1,000th of annual revenues, is a telling indicator of the company's technological prowess. Typically, such an item represents expenditures like payroll expenses, consultation fees, the cost of contract programmers, etc., that are added to the cost basis of the company's internally developed software. The spare investment in computer software and hardware in general, in combination with the tiny amount capitalized for customization and internal use software, reveals a company that may be woefully underinvested in the supply chain, inventory, and customer relationship management, or CRM, systems needed to keep pace day after day with worthy competitors such as Gap and Nike.

Perhaps this is why the company is spending $40 million on IT initiatives this year. New CEO Laurent Potdevin clearly sees that the company is lacking in crucial infrastructure. In the company's most recent earnings call, Potdevin readily admitted, on one of these fronts, that "[We've] never really used a lot of data in the history of Lululemon." Perhaps management formerly relied on its products' high demand and relative lack of competition, and didn't need the robust analytics that most companies in the fashion industry now see as a competitive necessity. Such is certainly not the case today.

Profits are what you make of them

Remember that high gross margin relative to peers? Lululemon's profits eventually made their way back to the company's bank account, as we've seen. But what if management had accepted a lower gross margin, hiring more specialists to oversee inventory and its supply chain? Perhaps better infrastructure in the way of technology and also people could have prevented the March 2013 recall of transparent black yoga pants, an event that proved to be a catalyst for present-day woes.

This is not to say that Lululemon has totally ignored investment in its future and the need to diversify revenue. The company launched its ivivva athletica line of activewear aimed at girls in 2009, and is selling an increasing amount of its products online. It's also ramping up international expansion in 2014 to spur growth outside of the company's core markets of Canada, the U.S., and Australia. But both ivivva and global growth are only in a nascent stage, while the company's same-store sales from its existing flagship yoga clothing and accessories are in decline. After more than four years, Lululemon has only 16 ivivva stores in operation, versus 247 under its Lululemon brand. And it will take another three years for the company to reach 20 total stores in Europe and Asia.

A recovery is possible, but not inevitable

Can CEO Potdevin execute a turnaround of Lululemon's fortunes? It's certainly possible, but Potdevin's success will depend on a number of conditions falling into place. The company will have to withstand potential pricing pressure from rivals. While expanding internationally and successfully growing ivivva, it will have to deliver on its technology investments and new product introductions to help turn around declining existing store sales. And Lululemon can't allow further blemishes from its supply chain that may again hamper the quality perception around its yoga apparel.

With 28.5% of Lululemon's outstanding share float sold short, one can surmise that short-sellers have also read the company's balance sheet and suspect that this emperor has no yoga pants. They are also particularly emboldened by a curious decision by Potdevin and the company's board to authorize $450 million in share buybacks over the next two years, an amount equal to 80% of the next two years' operating cash flow. After stockpiling cash for so many years, now is the time to actually keep dollars in the company coffers, both to invest in technology and store expansion and to be able to fend off any price challenge from competitors. The market's continued displeasure with Lululemon's shares probably indicates that it doesn't see the share buyback as a constructive use of resources.

To return to the question I posed at the outset, it's possible that at a 30%-plus discount from last year, Lululemon's shares represent a value investment. But risks abound, and a resurgence is by no means a given. If you're considering Lululemon as a value investment, a little patience and a review of next quarter's financials might be preferable to jumping in today.