You may not have noticed it, but it's now been a little more than a year since oil prices started their decline from more than $100 per barrel to the $40-$50 range, where oil is trading today, depending on the market's mood. Based on the amount of money that has fled the entire energy market, it appears that a lot of investors have changed their minds about investing in this space over the long term. Perhaps we all got swept up in the thrill of America's oil boom, or maybe we were still looking at investing in energy through the "peak oil" lens. Either way, something is decidedly different today.

So we asked three of our energy contributors to share a lesson they learned over this past year and how it has shaped their investment theory going forward. Here is what they had to say.

Matt DiLallo: The most important lesson that I've learned is that oil companies tend to be way too bullish on oil prices. This has clouded their judgment and led to some really detrimental decision making.

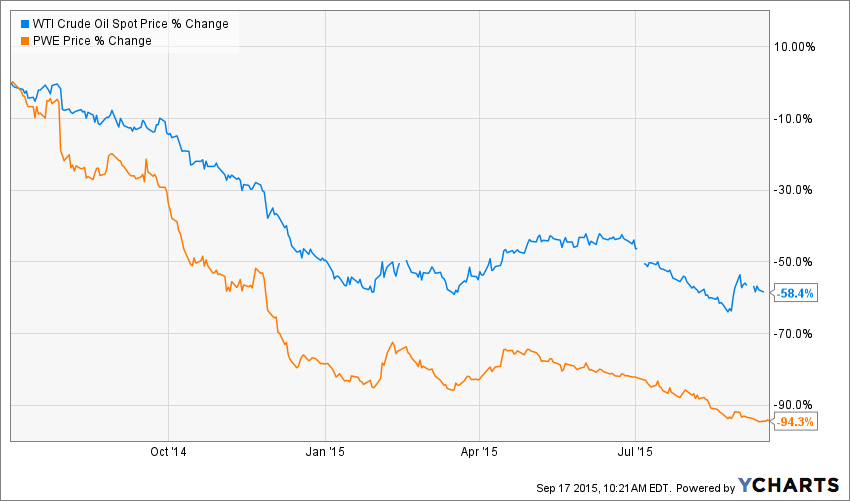

One of the most spectacular examples of this is Canada's Penn West Petroleum (NYSE: PWE). Last summer the company said, "As of July 1, 2014, we are now participating fully in the currently strong crude oil price environment with the last of our WTI hedge positions expiring on June 30, 2014. This allows us to immediately realize 100% of current market pricing, which currently exceeds our 2014 budget assumption by approximately $10 per barrel."

However, in an attempt to capture 100% of the upside to oil price, the company also exposed itself to 100% of the downside. And boy, was downside ahead:

WTI Crude Oil Spot Price data by YCharts.

Making matters worse, the company never accounted for the potential for oil prices to really crash after they started sliding. Later on in the year its CEO admitted, "Penn West's business model assumes a conservative long-term commodity price; however, the recent downturn falls outside our lowest probabilistic expectations." In other words, it never even thought a deep drop in the oil price was possible. By leaving that option off the table, it led the company to feel more comfortable with its ability to pay a high dividend and use debt to fund growth.

Penn West is far from the only company that was blinded by its bullishness. It wasn't alone in employing meager hedges, or taking on lots of debt to fund growth. Those decisions, however, really burned those oil companies and now they're struggling to survive.

This has taught me a valuable lesson, which is to be wary of oil companies that need high oil prices to maintain their operations. This means avoiding companies that use a high degree of leverage to fund growth. Instead, I'll focus my attention on companies that limit their use of debt and instead not only fund growth within cash flow but actually generate free cash flow.

Jason Hall: The thing people often ignore with the oil industry is that it's cyclical. The music eventually stops on every boom, and a lot of people look up and realize there are no chairs left:

WTI Crude Oil Spot Price data by YCharts.

The cycles don't always correspond with recessions (gray bars above). Because of this, it's not a "set it and forget it" industry to invest in, especially with companies that are heavily exposed to oil prices. This includes oil producers, drilling contractors, and other suppliers that get cut off when producers start slashing costs. The short-term pain can be really bad, and casual investors can get crushed.

Don't get me wrong: Almost nobody saw this sharp or long-lasting of a collapse coming, but the people who invested in the industry with the understanding that booms and busts happen, and diversified so that a major collapse wouldn't lead to outsize losses, are the ones who have come through in the "least worst" shape.

Unfortunately, casual investors who took on too much risk at $100 oil are paying the price.

The saddest part? As the downturn plays out, there will be some phenomenal investing opportunities ahead, but many of those who made bad decisions at the peak won't participate in the eventual recovery.

Tyler Crowe: The biggest lesson that I have taken away from watching how this decline has affected the finances of companies is that the idea of "growing into one's debt load" is a business strategy that is destined for failure.

Prior to the oil price plunge, we saw a flock of companies all head out into the oil patch and try to ride the wave of $100 oil, cheap credit, and a new technology to extract oil and gas from shale wells. That 4.5-year stretch where oil prices didn't go below $75 a barrel was a great environment to foster the development of this emerging extraction method, but the drawback to it was that far too many companies used it to justify growing production at a breakneck pace without any regard for their ability to find it.

WTI Crude Oil Spot Price data by YCharts.

I'm not saying that companies that take on debt are setting themselves up for a decline. The energy industry is an asset-heavy, capital-intense business, and when debt can be secured at cheap rates, it's worth considering because it can lower the cost of capital. That said, this is still a cyclical commodity business that requires prudent management of budgets and smart allocation of capital during all parts of the cycle, and any company that sows its balance sheet with a lot of debt will likely reap a weak harvest.

So going forward, I'm going to be very wary of companies that emphasize growth and lean on heavy debt to achieve it. Instead, I'm going to look for the companies that strive for disciplined capital management. The real test of this principle will come when the energy market surges again.