A couple months ago, a video depicting the (very short) flight of a new Portuguese Navy drone began circling the Internet. I'll pause for a moment and let you take a look:

Okay, now you'll understand what I mean, when I say that...

Europe's drone program is like Portugal's, writ large

For years, America has had a near-monopoly on the use of advanced unmanned aerial vehicles in combat. Sure, other countries have "drones" -- mostly small, reconnaissance birds that have more in common with a hobbyists model airplane than with a General Atomics' Predator.

But for real-world surveillance work in hostile environments, Europe generally has to buy drones built by American companies. Britain, for example, flies Global Hawks from Northrop Grumman (NOC +1.60%). France recently announced the purchase of Reapers from General Atomics. Germany leases Heron unmanned aeriel vehicles from Israel (aside from the U.S., the only other manufacturer of really high-quality drone aircraft).

General Atomics' Predator drone. Easily the most recognizable drone aircraft in the world. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

But as DefenseNews.com reports, there's great interest in Europe developing a homegrown drone-building program "to add reconnaissance and strike capability at lesser cost and risk to service members." Italian company Alenia Aermacchi, a subsidiary of Finmeccanica (FINMY +1.70%), has argued that a "European made UAV" is essential for "European operational sovereignty and independence in the management of information and intelligence."

And at last month's ILA Berlin Air Show, both Dassault and Airbus (EADSY +0.94%) announced a plan to collaborate on developing a medium-altitude, long-endurance, or MALE, drone similar to General Atomics Reaper and Predator drones. According to news reports, the new drone will feature long endurance and good maneuverability, and will emphasize reconnaissance capability over the ability to carry weapons. Their target date for first flight is 2020.

How to get to there from here?

The problem is that these three companies hail from three different countries -- Italy, France, and Germany. (Airbus is traditionally viewed as a French-German company, and S&P Capital IQ reports that even after its recent reorganization, the governments of both France and Germany own stakes in Airbus). And so these companies are asking three different governments to help build their drone.

Sources suggest that development of the drone could cost $68 million in just the first two years of the project, and potentially as much as $1 billion -- and that's just the development cost. Actually buying drones would cost even more money. Unfortunately for the companies, their host governments don't seem eager to foot this big of a bill. As German Defense Minister Ursula von der Leyen said, "At the moment there is no pressure to make a decision."

Too many irons in the fire

Further complicating matters, one of the corporate coalition's three members, Dassault, is already trying to build an unmanned combat drone in cooperation with Britain's BAE Systems (BAESY +1.62%). Given that it's already financing half the cost of building one drone "on spec," Dassault may not relish the thought of anteing up a third of the development costs of a second drone -- with no certain buyer. The more so, given that Dassault is under financial pressure after repeated failures to find international buyers for its Rafale fighter jet.

What it means for investors

If all of this makes it sound like Europe will have a hard time getting a homegrown drone program off the ground... well, that's my read on the situation, too. (Remember that poor Portuguese drone?)

This is good news for investors, though. It means that we can continue to focus in on the leaders in drone technology, and know that at least for the time being, U.S. firms such as Northrop Grumman and General Atomics will continue to dominate the drone space.

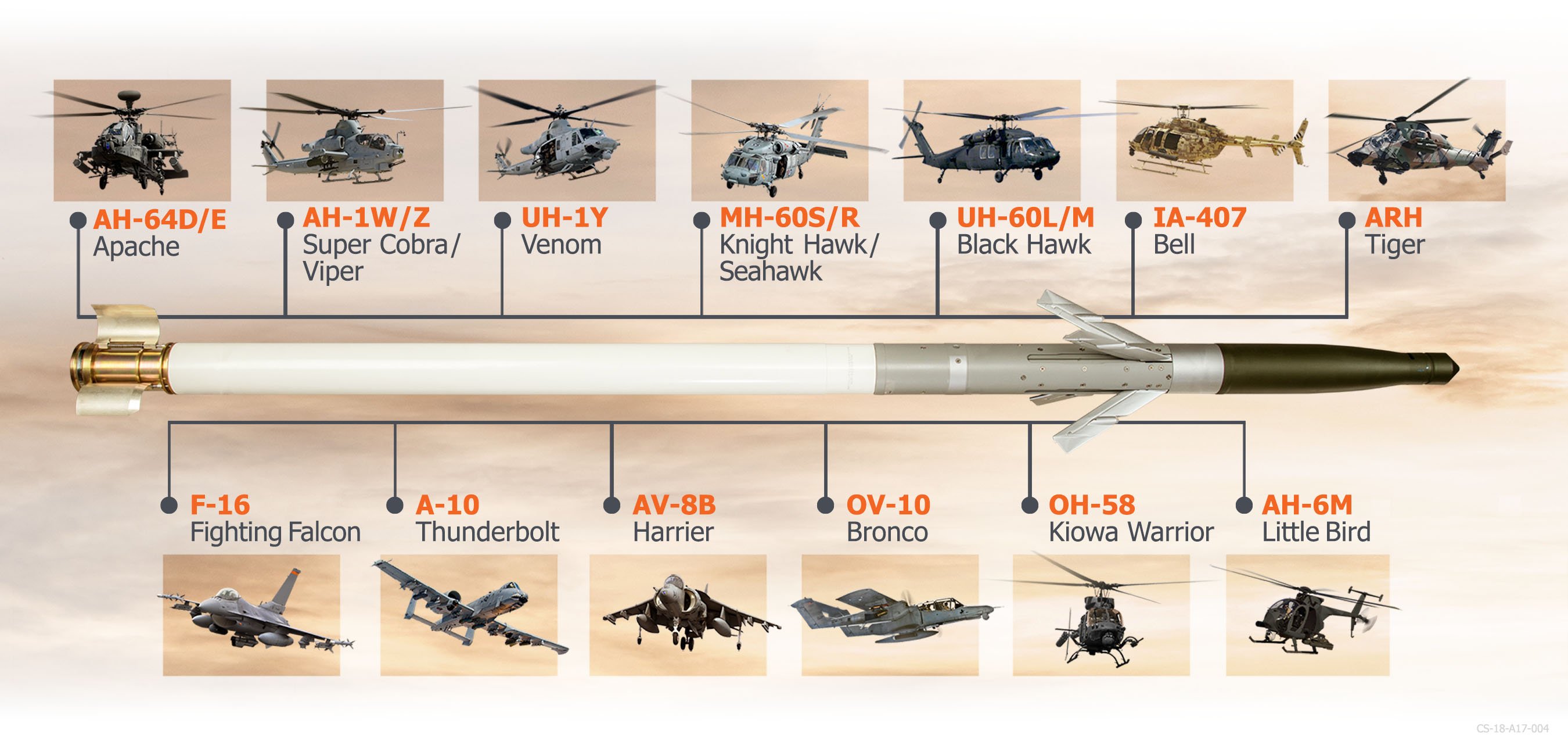

In fact, they might do even better than that. Reportedly, President Obama is currently considering signing a bill that would ease U.S. export restrictions on drone technology -- and in particular, on drones capable of being armed with air-to-surface missiles such as the Hellfire. To date, these restrictions have hobbled U.S. drone-makers, making it difficult for them to capture all of the market share worldwide that their superior drone technology would ordinarily win for them.

Industry analysts estimate that the global market for drones could exceed $60 billion in value over the next seven years. If President Obama approves expanded drone exports before Europe gets its drone building act together, I'd give good odds on U.S. companies winning a large portion of those sales.

General Atomics' Reaper drone is silent, deadly -- and profitable. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.