In the following video, 3-D printing specialist Steve Heller interviews Mcor Technologies CEO Conor MacCormack about the company's positioning in the 3-D printing space. Mcor makes 3-D printers that use ordinary copy paper as their primary material and cost significantly less to operate than competing professional 3-D printers. The company is headquartered in Dunleer, Ireland.

Topics covered include:

- An introduction to Mcor's business

- How much it costs to operate Mcor 3-D printers

- Mcor's competitive positioning in the marketplace

- Mcor's future plans for expansion in services

- How Mcor differentiates itself from 3D Systems (DDD 2.62%) and Stratasys (SSYS 0.66%)

- Mcor's plans to go public

A full transcript follows the video.

Steve Heller: Hey Fools, Steve Heller here. I'm joined today with Conor MacCormack, CEO of Mcor Technologies. Mcor is a very exciting company in the space; they are disrupting 3-D printing materials in particular.

I wanted to ask you, Conor, about your position in the marketplace compared to the competition, and what makes your product so unique.

Conor MacCormack: Thank you for the opportunity to speak here. Effectively, we have a very differentiated product. We looked at the industry almost 10 years ago, and we felt it was one thing that the price of the machines was coming down a little bit -- the capex -- but the running costs were going in the opposite direction.

Almost like, 10 years ago, you needed the same price per volume as gold; ridiculous things were going on then. So, we felt if we could build a machine that was really, really accessible, that anybody could load the material into the machine and almost have a zero running cost, that that's what everybody would want.

That was a challenge. We decided to build a machine that was very accessible, that was going to upset the status quo. We said, "What's the most readily available material, that anybody could get their hands on?"

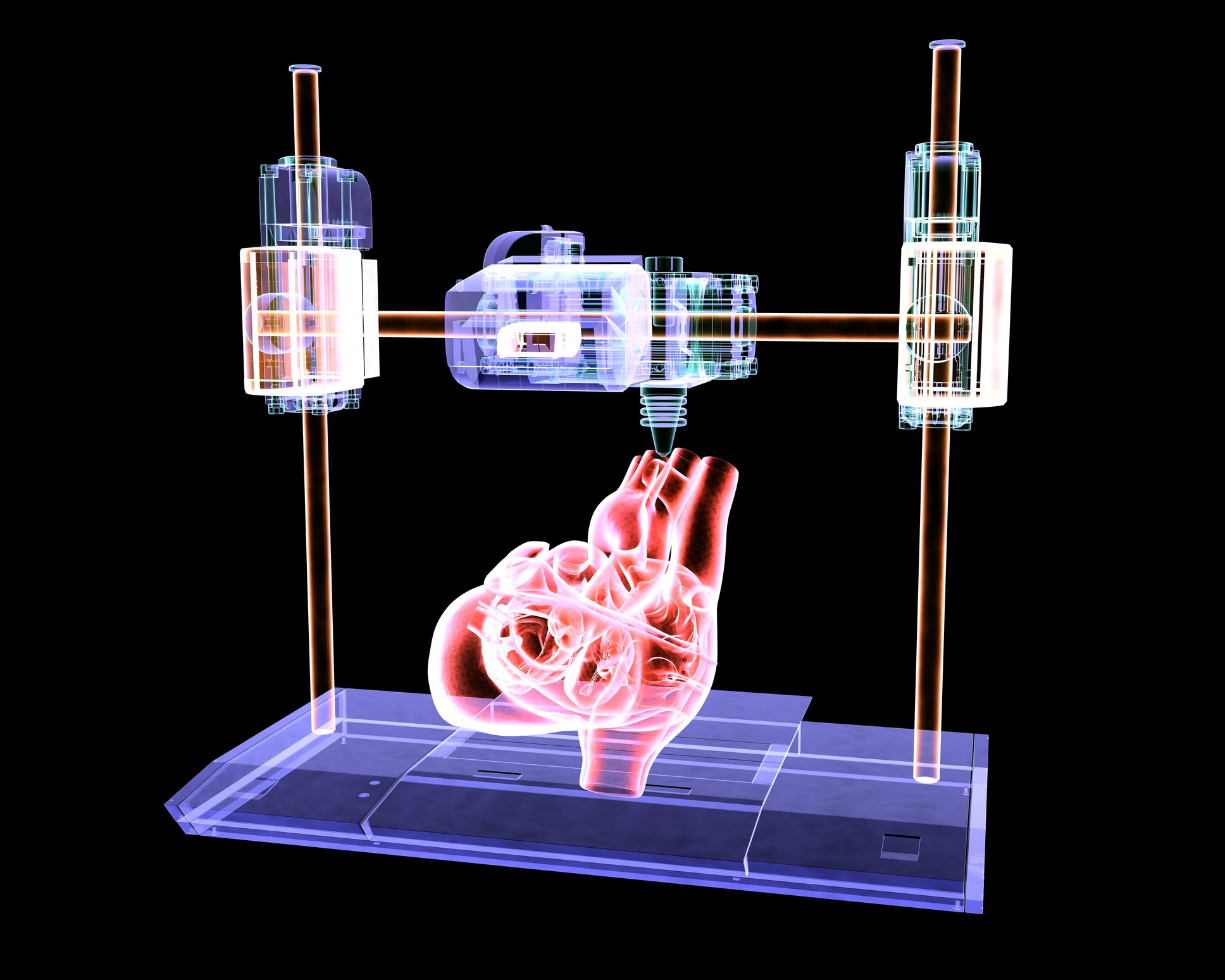

We said, paper. Everybody can go to the photocopier or go to the printer, pull out a couple of reams of paper, and load it into a 3-D printer, so we said, "Let's start at that point, build a paper-based 3-D printer that ran on a water-based adhesive," because in time we could always see these machines in schools and in universities, and maybe in time, even homes -- but we're not there yet.

We felt it couldn't have extraction fans, powders, really complicated chemicals. We just wanted to really keep it simple, but really build a machine that was going to upset everybody -- and that's what we did.

At the very basic level, you take three reams of standard photocopier paper, you add it to our Mcor IRIS printer, and you get full-color, robust and durable, eco-friendly 3-D printed parts.

We're very different from everybody else. Everybody else has a traditional razor-and-blade model. We almost have an inverted model -- which can be a challenge because in the investor community, they say, "These companies are making 40%-50% of their revenue on the consumables."

But the way we looked at it was, the penetration was so low the problem why we're not getting bigger penetration is because the running cost was so high. We just really made a very strong statement that said, "Let's have a very low running cost, and let's try and get more penetration of the machine into the industry."

Heller: How much cheaper, on average, is your product -- using it -- versus the competition?

MacCormack: It ranges, depending on if it's a full-color machine or if it's a part that you just put different colored paper in. It can range between five times up to 30 times.

Heller: Wow.

MacCormack: If it's a white part, or a solid color like a blue or a green, or layers of color, you can get that with just putting layers of colored paper into your paper tray, and it can be up to 30 times cheaper than plastic.

If you want a full bitmapped color, like if you're printing out somebody's face or a landscape, then you're around 5 times cheaper than the next color printer.

I think the waters are getting cloudy about what happens in color printers. People talk about true color plastic printers, but actually there's only two technologies out there that can print in full color.

The definition of "full color" is that, at any time when the head is moving around, it needs to be able to put down any color. It needs to be instantly changed from one color to another at any time. If your machine can do that, it's true color.

If it's blending plastics or doing something else, it'll be one color to another color, and it will slowly go from one to the other. Something like that could never print out somebody's face or some sort of a landscape, so there's a bit of a definition that needs to be done in the industry.

Heller: Right.

It sounds to me like your product is more geared toward the prototyping market. What kind of applications is your product best suited for in that market? What are you most excited about as an opportunity?

MacCormack: For us, when we had this idea, obviously it was running costs. We felt that was the problem. But when we started to build the machine, and people got a chance to actually hold the parts, people said, "There's a fantastic feel of these objects. They're very, very smooth."

People have built up kind of a database over the years of handling paper. There's a very nice tactile nature to the parts.

Our biggest use cases are really, as you mentioned, the early stages of the designer view. Prototyping -- a lot of people on Wall Street talk about, "Well, if it's not part of a jet engine or something that goes into a spacecraft, how would you use it?"

But the reality is, on the street, maybe 75%-80% of what people use 3-D printing for is non-functional. They want something that's a nice, low price point, high quality, and if you can get color in there, all the better.

Heller: You have a great proof of concept then.

MacCormack: We're going after the same markets as everybody else. You have product designers, you have architects, you have MCAD industrial design, you have GIS -- Geographical Information Systems -- all the usual suspects in the commercial side, we'll be going after.

But also, with our technology, we have access to the consumer. The consumer might not be buying our machine right now because of the price point, but the content out of the machine is very much a consumer-oriented product. It's high color, high quality, and that's going to happen, we feel, via retail.

Just like you would see in 2-D printing, where people would get their 2-D photographs printed in a local store, in high-quality printer in the back room, we believe that that's how consumers are going to get access to high-quality 3-D printing, via the retail. We are very well geared for setting that up, this year or next year.

Heller: Right.

You have something set up like that in the Netherlands with Staples, is that correct?

MacCormack: Yes.

Heller: How is that going for you?

MacCormack: It's going very well. As we said, Staples in the Netherlands and the Benelux region is looking after that. You can go to a website called "My Easy 3D," you can upload your content, and you can get your parts printed out exclusively on an Mcor product.

Staples in the U.S. and Staples in Europe are very different entities, but we do believe that that was a proving ground for us, as a company, to realize that this is a vehicle for Mcor to get access to the consumer.

We're already talking to very big global brands about doing something very similar, but on a global level. One of the biggest frustrations, especially in the U.S., was people saying, "Well, this is brilliant. I can go to my local Staples store," but it actually was only available to people in the Netherlands.

Now we're expanding that out with other companies, with the same kind of a business model -- where people upload their content or take a photograph and try and make that into 3-D, or use a scanner or a Kinect scanner, or whatever the easy ways to get 3-D data -- and walk into a store or go to a place where you get your 2-D photographs printed, and get that now printed out in 3-D.

That, we believe, is how the consumer segment is going to grow.

Heller: Yes. Mcor Technologies is coming to Shapeways hopefully, in the future, or taking on Shapeways. It sounds like interacting with a service center is going to be a bigger area of focus for you in the future.

MacCormack: Yes. For our company, we will see ourselves as an R&D company. We develop new products, and we bring these products to market. But we always see the opportunity here, and there's a huge opportunity here on the service side.

A lot of the big companies that we're up against will have their own service arms, but we get a lot of requests from people about doing service. We think that the consumer segment is a perfect vehicle for that to happen.

We have very good dealers globally, around the world, that sell our products on the industrial side. But on the consumer side, we need something a little bit different. As I said, some of the new products that we have coming out in the very near future are really, we believe, going to take the 3-D printing world by storm, again, like they did when we came out with our first paper printers, many years ago.

Heller: It sounds like you're playing in the same waters as the big players -- Stratasys, 3D Systems. You're more of a smaller company; a few hundred systems installed worldwide. How do you go about growing your install base and increasing awareness that your product is serving that same exact market and doing it great, for a fraction of the cost?

MacCormack: It's all about awareness levels. Going to a show like this is very important. We do a lot of shows in the U.S., a lot of shows across Europe. It's a lot of getting the information out via social media, all the social marketing that we do, so that's a big thing.

But you're correct; we do compete against these very big companies. My philosophy has always been, if you have a good idea, it's a good idea. If it's a good product that will stand up for itself, people will want to use it -- and it's starting to happen.

People are starting to say, "This is something very different." It produces a great part, extremely high color, very low price point, and the product stands up for itself. Really, it needs to be able to stand up for itself, but I think that's the way the future of 3-D printing has to happen -- like you go into a Best Buy and you see all the different types of mobile phones -- it has to get like that.

Heller: Sure, commoditize, yes.

MacCormack: Yes, because at the moment, if you're a dealer, you're locked into that.

Heller: Exactly, that agreement and that ecosystem.

MacCormack: Yes, you're locked into that system and just that one machine, or two, three, four machines of that particular company. I think for the future of 3D printing over the next five to 10 years, it has to become a lot more open.

Heller: Sure.

Final question for you today; I know you're doing very well. It sounds like the company is growing. Do you have any plans to go public in the future?

MacCormack: Well, we've made a decision. We're in the process of doing a very big funding round in the company, so we've made the decision to build the company up, to develop this new IP that we've filed, to bring these new products to market. Then we'll see what happens.

I think people are almost putting pressure -- "You need to IPO because the market's going to stay open" -- but if you have a very good product, and you have a very good company, I think the market will always be open.

We believe that we'll be in that situation this year or next year. We'll have a very well-established pipeline of dealers, very successful growth like we've seen over the last couple of years, and the new products that are about to come on the market.

It will be a very good story, and we'll see what happens then. My goal is to build this company up to be a multibillion-dollar company, in whatever way that happens -- if we can do it just by raising our own money, if we need to go IPO -- but the main thing is that we get these products out, and we get these new machines out and [unclear]. Whatever's the best way for that to happen.

Heller: Sure, so it's more about the best interests of your business. You're not thinking short side, you're thinking long term and how to strategically place your business to win over the future.

MacCormack: Yes. I think a mistake that a lot of people think in this industry is that all the innovation is done. They think that whatever 8 or 10 platforms, that there's no more innovation going on. Like that famous quote from the patent office, that you might as well close the patent office...

Heller: Exactly.

MacCormack: I know we are working on some stuff that's really ground-breaking. I know people throw that around a lot, like "the next revolution" and all, but we have some stuff that is really, really new.

I'm sure some of these other companies are doing the same, and if these pan out, who knows what's going to happen in the future? We really believe in our R&D's strengths, and we believe that these products will come to market, and we believe that Mcor can be a very, very big company in the future.

Heller: Great. Thank you so much, Conor, we really appreciate your time.

MacCormack: No problem. Very nice meeting you, Steve.