Things sure are more expensive than they used to be. A gallon of gas was once less than $1. A newspaper could be gotten for $0.05. But on the other hand, your house is probably worth three or four times as much as it was a few decades ago.

Remember the $0.15 hamburger?

Source: Democratic Underground.

Prices rise all the time, whether in response to high demand or to account for the costs of doing business. But when prices rise across an entire economy, it's called inflation, and it can make a huge difference in both your standard of living and the health of the economy in which you participate.

If you've been wondering how inflation works and how it's measured, you've come to the right place.

What is inflation?

Inflation is what happens when prices across a large range of goods and services increase at the same time. While this seems intuitive to anyone who has lived through decades of rising prices, inflation has been far from constant in the past, and economies around the world have actually suffered extended periods of falling prices, which is known as deflation.

During times of inflation, a dollar loses its purchasing power -- that is, one dollar buys less in goods or services than it did before. Thus inflation and deflation measure how far consumers can stretch a dollar in their pockets over time.

For example, when people say the minimum wage isn't worth as much as it used to be, they don't mean that people used to get paid a higher minimum wage -- at $7.25 an hour, the national minimum wage has never been higher -- but rather that an hour of minimum-wage work used to allow people to buy more in goods and services than they can get from working that minimum-wage hour today.

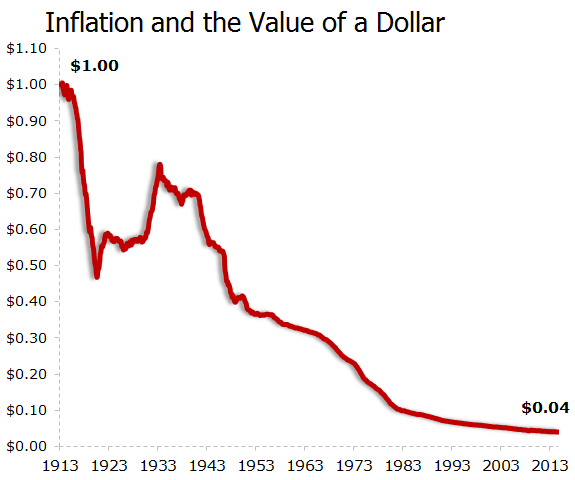

Over time, the purchasing power of a single American dollar has plunged, as you can see in this chart of the purchasing power of a consumer dollar from 1913 to the present day:

Source: Federal Reserve of St. Louis.

A century ago, your dollar bill could have bought a dollar's worth of stuff. Today, that same dollar can only buy the equivalent of $0.04 worth of stuff. In nominal terms -- that is, before adjusting for inflation -- you have the same dollar today that you had a century ago. In real terms, which are adjusted to account for inflation over time, that dollar is only worth $0.04 -- or 96% less than it was worth a century ago.

To some people, this graph looks like an economic catastrophe. But it shouldn't, because inflation isn't the only thing that influences your purchasing power. We'll explore the benefits and the drawbacks of inflation later in this article, but first, let's try to understand why inflation actually happens.

What causes inflation?

There are two primary types of inflation: demand-based and cost-based. When demand drives inflation, more money is chasing the same amount of goods and services. The economy can't produce more stuff, but it can spend more on the same amount of stuff, so consumers bid up prices.

When inflation is driven by costs, it means the stuff that goes into producing goods and services, whether employees (due to rising wages) or raw materials (due to limited supplies), is costlier than before. As a result, the price of goods and services rises as businesses seek to maintain profitability in the face of rising costs.

Source: Flickr user AgentAkit.

Events like the oil price shocks of the 1970s are highly visible examples of cost-based inflation, but they're less common than demand-based inflation, because the latter can be influenced by central banks, like the U.S. Federal Reserve. A central bank controls interest rates across the financial sector, and the goal of adjusting interest rates is often to keep inflation within certain boundaries -- usually at or below 3% per year.

Lower interest rates, like the rock-bottom rates of the post-crisis era, encourage consumers and businesses to borrow and spend, which puts more money into the economy. High interest rates, like the record-high rates implemented in the late '70s and early '80s to combat oil-cost-driven inflation, discourage borrowing and make it more appealing to save, which reduces the money that flows through the economy.

Central banks can also "create" money by buying up financial assets or lending to financial institutions, which puts more money directly into the economy. No new money is actually created in this case, but the total money available in modern economies is only loosely connected to the amount of coins and bills in circulation. This "money-printing," as it's often (and incorrectly) called, does run the risk of causing excessive inflation if too much new money reaches public hands all at once; but the Federal Reserve and other central banks have so far been adept at managing the money supply.

What are the pros and cons of inflation?

A modest amount of inflation is good for an economy. If consumers and businesses expect prices to be higher in the future, they're more likely to spend money in the present to get a better deal.

Inflation also reduces the real value of debt. If you took out a $100,000 loan 10 years ago, you're probably paying the same monthly amount toward that debt now that you were 10 years ago, and you'll probably be paying the same monthly amount 10 years from now. But thanks to inflation, you're (probably) earning more money every year, even if you're not going anywhere in your career, making it progressively easier to pay off your debts over time.

It's worth noting that the minimum wage is actually higher now than it would be had it simply tracked inflation from the very beginning. It's also worth noting that the average American worker's hourly wage has risen from $2.50 in 1964 to nearly $21 today, which actually means that hourly wages have been more or less flat after accounting for inflation for 50 years. Make of that what you will.

Too much inflation, however, is very dangerous. If prices rise too quickly, wage earners will usually find that their paychecks can't keep up, resulting in shortages of critical goods. If a nation's money supply explodes, money itself can soon become worthless, and the national economy can fall apart as people lose confidence in their currency.

This runaway inflation is called hyperinflation, and the worst episode ever recorded took place in post-World-War-II Hungary, which wound up with so much worthless money that its citizens wound up sweeping them into the sewers to keep the streets clear of banknotes. This doomsday scenario is unlikely to happen in modern developed peacetime economies, but it remains a persistent danger in the minds of some monetary extremists.

World War II propaganda poster. Source: U.S. National Archives.

Too little inflation, which can soon tip over into deflation, is also dangerous. Just as people spend when they expect prices to rise, they're also likely to hoard money when they expect prices to fall. This can quickly devastate an economy as millions of people hold out for better deals at the same time.

Deflation seems great on the surface for lenders, who wind up with debts that become worth more over time as the value of a dollar rises. However, debtors suffer terribly in deflationary episodes, as they not only have to pay off the same debt with smaller paychecks, but they also find that the value of whatever secured that debt has become worth less than the debt itself.

This unfortunate phenomenon, called being "underwater" on one's debts, is what happened to millions of homeowners during America's financial crisis when the prices of their properties tumbled. Because so many of these underwater debtors simply default rather than continue to carry the weight of an unsustainable loan, deflationary episodes tend to drive many financial institutions out of business.

Inflation is like water to an economy. A healthy body needs water to thrive, but too much or too little of it can kill. For the past 30 years, inflation has been remarkably stable in the United States. The rate of annual inflation has only risen higher than 6% for four months out of those three entire decades, and the economy suffered through a modest (by historical standards) seven-month deflationary episode only in the aftermath of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

In contrast, inflation grew by double digits -- 10% or more -- from early 1979 through the end of 1981, and the Great Depression produced more than three straight years of deflation, with all but the final month of 1932 enduring double-digit price declines. Policymakers now make every effort to avoid the extremes of the 1930s and the 1980s, which is why the chart above looks so smooth once it hits the 1980s after decades of violent swings. With enough skill and a little luck, they'll be able to sustain only modest levels of inflation for many years to come.