USS Freedom (LCS 1), America's first Littoral Combat Ship. Photo source: Lockheed Martin

For America's defense contractors, it's all over but the crying -- and for two companies, the cheering.

Eight long months the U.S. Navy kept us waiting as it mulled improvements to the much-maligned Littoral Combat Ship -- a vessel famously criticized by the Pentagon's own Director of Operational Test and Evaluation as "not expected to be survivable in high-intensity combat."

At least four companies submitted plans to build a more robust replacement, but in the end, the Navy decided to go with the flow. Rather than build a new frigate for the 21st century, the Navy announced last month that it will stick with its original LCS designs, making only minor upgrades.

Result: Our new Small Surface Combatant will look a lot like our current Littoral Combat Ships. Either like the version from Lockheed Martin (LMT +0.28%), shown above, or like this trimaran variant from General Dynamics (GD 1.34%) and Austal (AUTLY +0.00%):

USS Independence (LCS 2) -- General Dynamics' answer to LockMart's design. Photo source: General Dynamics.

LCS: Version 1.0

"A lot like" -- but not exactly the same. The Navy originally designed the LCS to perform three missions: surface warfare, antisubmarine warfare, and minesweeping. And so that one ship could perform all three missions, the Navy built the LCS according to what I call the "Lego principle."

The LCS is like a Lego base plate, onto which can be fastened whichever "Lego bricks" (Mission Modules) are necessary to build a Mission Package (e.g., warship killer) to perform a given mission. So, for example, an LCS dispatched on a surface warfare mission might be outfitted with MK 46 cannons, surface-to-surface missiles, and an MH-60R Seahawk helicopter.

Later on, should this same LCS be tasked with minesweeping, the cannon and missiles might be swapped out for extra sensors and a squadron of unmanned mine-seeking robotic submarines...

LCS: Version 2.0 -- the Small Surface Combatant

Instead of this plug-and-play solution, future LCSes designated "Small Surface Combatants" will all receive a standard equipment package, permanently installed. According to the Navy, this will include:

- Improved radar, electronic warfare, and sonar packages.

- SeaRAM missiles for self-defense (built by Raytheon, SeaRAM is similar to the Phalanx Close-in Weapon System, but shoots down hostile missiles with its own guided missiles, rather than with "bullets").

- An over-the-horizon antiship missile, perhaps Boeing's improved Harpoon II, for offense

- Mk 38 25mm machine guns (for dealing with small targets such as gunboats)

- Improved armor for "vital" areas of the warship, to improve its ability to survive a direct hit.

Lockheed, General Dynamics, and Austal will build 20 such SSCs. Not together, but it's gotten more complicated recently. To untangle it for you: LMT will build 10. GD built 3 with Austal. The next seven of their ships will be built by Austal, with GD doing significant work on the systems that go onto the ships. They're still closely associated, though, but technically, the contract is Austal's. These will be in addition to the 32 LCS v.1.0 vessels already scheduled, which will largely be relegated to tasks currently performed by the Navy's current fleet of 26 minesweepers. Aside from the upgrades, the major difference between the two classes of warship is that the Navy says the SSCs will cost "less than 20% more" than the LCSes. That's convoluted grammar, but what it adds up to is that your average SSC could cost as little as $430 million, give or take a mil.

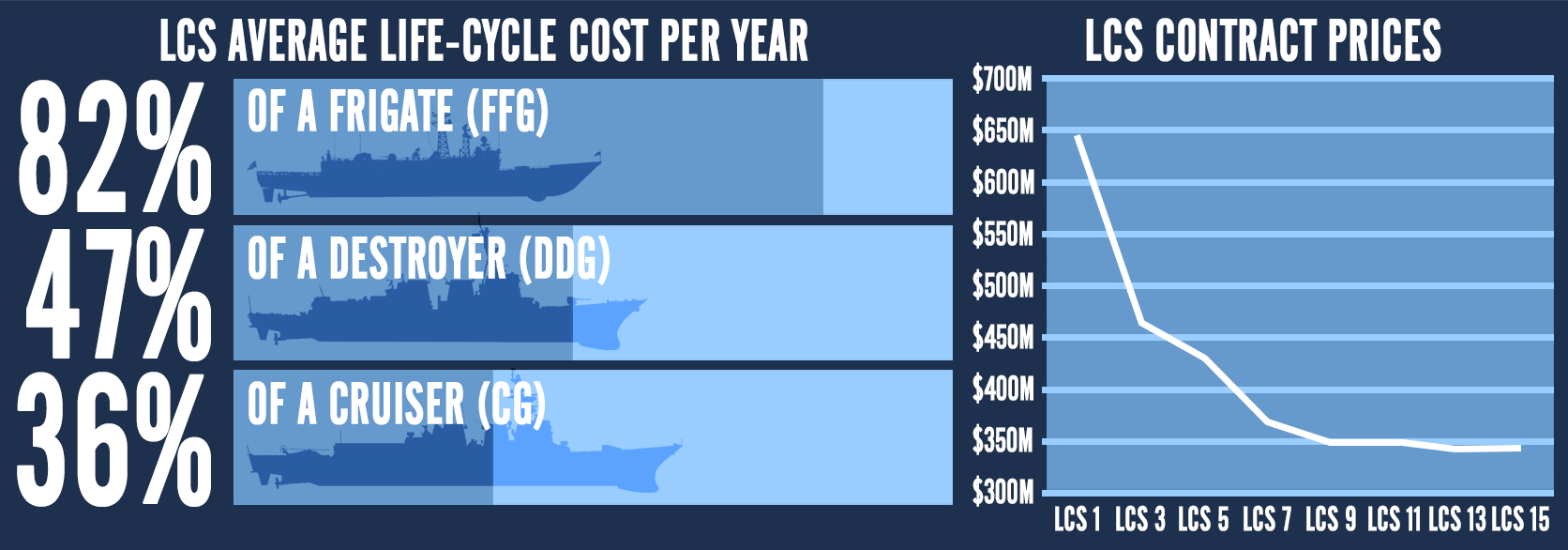

LockMart's estimate of an LCS's cost. Add 20% for an SSC. Source: Lockheed Martin.

What it means to investors

Here at The Motley Fool, we're as interested as anyone else in keeping up with developments within the military-industrial complex -- but what we really enjoy is figuring out how this kind of news affects investors' portfolios. So, what should we be looking for here?

First and foremost, the Navy's decision appears to dash Huntington Ingalls' (HII 0.05%) near-term hopes of "owning" any new classes of warship. Already, Huntington has been dropped from the competition to build the Coast Guard's new Offshore Patrol Cutters (a $12 billion contract, for which General Dynamics is currently the front-runner). Now Huntington has been shut out of the "frigate" market as well. That's a big blow for the company, which only took in $7 billion in revenues last year (according to S&P Capital IQ data), and would have sorely liked to win this contract.

In contrast, the winners here are the incumbent LCS shipbuilders: General Dynamics and its partner Austal, as well as Lockheed Martin. Together, these companies will not only get to build out the currently planned fleet of 32 LCSes (of which 20 contracts have already been awarded), but also 20 more new SSCs. Using Lockheed Martin's cost estimates as a basis for projections, this suggests these companies could end up splitting $8.6 billion in incremental revenues from SSC contracts. (Using independent third-party estimates of the program's cost, this money-haul might be as big as $16.3 billion.)

Precisely how much money will go to which specific contractors remains to be seen, as the Navy has not awarded actual SSC contracts at this time. Of the three, Austal, with just $1 billion in annual revenues last year, has the most potential to benefit from the Navy's decision to build its SSCs along the same lines as its LCSes. General Dynamics ($30.8 billion in trailing revenues) has the next most to gain, followed by Lockheed Martin ($44.6 billion).

But considering that just a few months ago, we weren't sure any of these three companies would get to build any of these ships at all, they all appear to be in line for a very nice cash windfall.

8 LCS's down, 24 to go before we see an SSC. USS Montgomery (LCS 8) is the most recent LCS v.1.0 vessel to have been christened by the Navy. Photo source: General Dynamics.