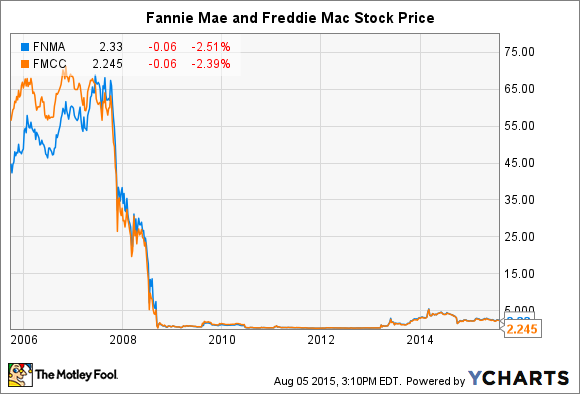

In 2008, the U.S. government intervened in the U.S. housing market in an unprecedented way. The government placed the two government-sponsored mortgage entities -- Fannie Mae (FNMA +0.00%) and Freddie Mac (FMCC +2.37%) -- into a conservatorship. Since then, many investors have been largely wiped out, new opportunists have raced into the stock, while others have fled in droves. It's been chaotic and downright confusing.

If you're interested in possibly investing in either of these mortgage giants, it behooves you to take a moment to understand these two critical facts before you click "buy."

Image source: Getty Images.

1. How do Fannie and Freddie actually make money? (Hint: Not by lending, exactly.)

Fannie and Freddie are both considered secondary market participants in the mortgage market. That means they don't actually make loans, even if they are the gorillas in the mortgage loan room.

Fannie and Freddie buy groups of mortgages from banks and originators all over the country. For the banks, this allows them to get cash quickly for their mortgages instead of having to sit on them for 10, 15, or even 30 years before profiting. That cash can then be used to originate more mortgages, which generates more available financing for Americans to buy homes. Banks win. Homebuyers win. It's a decent system, overall.

Once Fannie and Freddie own the mortgages, they take the groups they've purchased and bundle them together into even larger groups. These packages of mortgages, called mortgage-backed securities, are then sold to large investors all over the world. Fannie and Freddie guarantee the payments, removing credit risk from the equation of those large investors.

Profits come from transaction and guarantee fees charged for managing and servicing the mortgages, as well as earning interest income from the mortgages they hold on their books less the cost of their funding.

Fannie reported net income of $1.9 billion in the first quarter of 2015; Freddie reported $4.2 billion for the second quarter of 2015. Fannie had not release second-quarter results for 2015 at the time of this writing. For comparison, at the peak of the market before the crisis in the second quarter of 2007, they reported net income of $1.8 billion and $764 million, respectively.

In other words, now that the mortgage market has settled down after the crisis, Fannie and Freddie have essentially returned to form. Today, they're both producing profits very similar to historically normal levels. Why, then, are their market caps and stock prices as beaten and bruised as they are?

2. The biggest shareholder of Fannie and Freddie is Uncle Sam, and that's kind of a problem for investors.

Uncle Sam plays by his own rules. It's just the nature of the beast. It means that politics will play a huge role in his investment decisions. It means that shareholder interests don't necessarily come first (or second, for that matter).

To illustrate the problem with Uncle Sam as shareholder, we need to briefly jump back to the start of the financial crisis. In September 2008, the U.S. government bailed out both Fannie and Freddie and placed them into a conservatorship under the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

What was once an implicit backing from the Fed instantly become an explicit guarantee. Under the terms of that bailout, Fannie and Freddie individually issued new preferred shares to the Treasury that were to pay a dividend between 10% and 12%.

That's all well and good, except that neither Fannie nor Freddie could afford to pay the dividends for the first three years after the preferred shares were issued. That non-payment prompted the Treasury Department to change the terms of the shares.

Today, under the new Treasury requirements, Fannie and Freddie are required to pay 100% of their earnings to the Treasury as dividends. That, in turn, leaves 0% for shareholders.

Large, litigious investors like hedge fund managers Bill Ackman and Bruce Berkowitz think that this arrangement is not only unfair to shareholders, but it's also illegal. Ackman, Berkowitz, and others are suing to return the terms of the preferred shares back to the original terms. There have been at least 20 separate suits regarding these preferred shares over the past few years.

Ackman et al argue that the Treasury violated shareholder rights, overstepped the legal limits of the conservatorship, and perhaps even violated the Fifth Amendment, which states, among other things, that the government cannot take private property for public use without just compensation.

So far, the lawsuits have had mixed results. A U.S. District Court judge dismissed a group of about 10 lawsuits late last year, but other suits have found more favorable judges willing to hear the arguments in different jurisdictions. The outcome is anything but certain, but most legal and investing observers anticipate the Treasury will prevail.

What this means for shareholders

In this light, Fannie and Freddie present a tough conundrum for investors. On the one hand, they are a core piece in the U.S. mortgage market machinery, a market that is vast, profitable, and critical to many core American values. These companies have the potential to make a ridiculous amount of profit.

On the other hand, the U.S. government owns about 80% of the company, and history has shown that the government will wield that power without concern for the other 20% of shareholders.

Nothing captures this dichotomy better than the actual dividend payments themselves. Since 2012, the two GSEs have paid well over $200 billion in dividends to the Treasury, exceeding the $187 billion needed to bail them out in the first place. And yet, the 100% dividend requirement remains in place.

Several bills have been introduced in Congress over the past few years that could shape the future form of both Fannie and Freddie. Some bills sought to make it illegal for the firms' dividends to be paid to the Treasury. Most of the others, however, called for them to be dismantled altogether, one way or another.

There's no way to predict how the politics will play out, and that's why I view both Freddie and Fannie as speculative bets at best. Yes, both stand to make billions. And, yes, their stock prices today dramatically undervalue their economic potential. However, the political and legal risks are simply too uncertain.

In my view, the most prudent, best option for long-term investors is to simply sit tight and wait for the political and legal drama to settle. When the decision is once again about investing, and not Uncle Sam, then revisit the companies on terms we can more easily predict.