Last week, a few of my family members emailed me, very concerned about the stock market. They said:

- "My retirement can't afford another 2008-2009."

- "Is this 2008 all over again? Or is it worse?"

- "You work on stocks every day; should I be selling?"

I'd wager that many of you have similar concerns. We all do. It's human nature to feel fear when huge sums of money -- some of it being our own retirement funds -- vanish over a few short weeks.

My response to my family is the same as my response to you today: Don't panic. If your investment horizon is longer than three or five years, I think the best move is simply to do nothing. The market chaos this year is being driven by short-term phenomena and fear, not a major problem with the economy that could do serious damage to your portfolio.

This is not 2008 all over again...not even close

In a recent newsletter from stock and bond fund manager Cumberland Advisors, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer, David Kotok, shared what I think is a perfect drop of wisdom for investing in the market today. He said: "Hope is not a strategy. And fear provides the entry signal."

In my view, what's been going on so far this year is nothing remotely close to what happened in 2008 and 2009. That financial crisis -- emphasis crisis -- was the result of a once-in-a-generation de-leveraging across both the consumer and business economies.

In 2008, credit contracted, everyone de-leveraged, spending stopped, and the economy fell off a cliff. The economy today isn't seeing this same phenomenon. In 2016, banks are still lending, people are still borrowing, and the gears of the credit markets are still turning.

Banks have far stronger balance sheets today, central banks around the world have much better crisis-prevention systems in place, and businesses and consumers carry far-less debt than they did eight years ago. For all these reasons, I feel comfortable saying that this is not 2008.

Jack Bogle, investing legend and founder of Vanguard, advised investors to "stay the course" in an interview this month. He said that "these moves in the market are like a tale told by an idiot: full of sound and fury, signalling nothing."

The three reasons the market is crashing

With the credit markets still functioning, it stands to reason that any headwinds that may face the labor market, productivity, or any other major economic measures in the U.S. will not approach the force of the problems in 2008. I'm not saying all is perfect in the world, but I'm quite confident we are not on the cusp of another crisis.

If you believe me that the world isn't on the verge of economic collapse, the next task is to figure out why, then, the markets are behaving wildly. I see three primary drivers.

The price of oil is ridiculously low, and that's creating some chaos

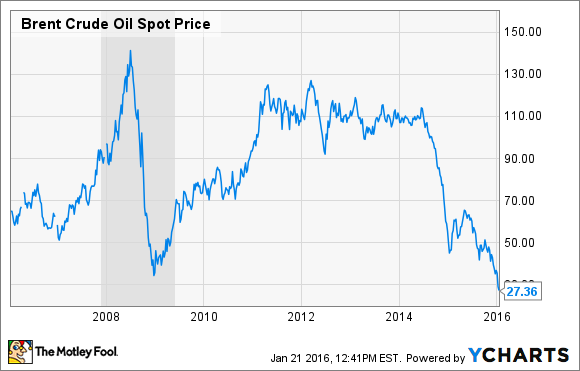

First, we have oil prices at the lowest levels in 12+ years, trading below $30 a barrel at the time of this writing. These low prices are wreaking havoc on the energy sector, and that stress is trickling through to some banks and other related industries. In supply and demand terms, the oil markets are reacting to a slowing China (more on that later), and a supply excess from new sources like the U.S., and unabated pumping from Middle Eastern players. Low demand and oversupply will always send prices lower.

However, experts have estimated that upwards of 40% of all oil-market trades are from speculators, not actual producers or consumers. This means two things. First, low prices from heavy speculation is not reflective of real world economic problems, and certainly not the type that could crash the economy like the credit crisis did in 2008.

Second, the speculation can exaggerate, or even disrupt, the true balance of supply and demand. We saw similarly wild swings in 2008 and 2009 as the world came to terms with the great recession. That drop in prices quickly recovered, essentially doubling over each of the next two years.

Brent Crude Oil Spot Price data by YCharts.

Could oil stay at these low prices for some time to come? Sure. Many smart analysts are predicting exactly that. But at the same time, I wouldn't be shocked if oil was back to $80-$90 a barrel by this time next year, or the year after. Recent history has shown that these kinds of reversals are possible, and with such high speculative interest, it seems quite plausible.

Making sense of slower growth in China

Second is the slowing growth and market volatility in China. The world is accustomed to 8%-10%+ growth rates from the Chinese economy. Now, however, it looks like expectations going forward should be more like 4%-6%. The latest official growth rate was 6.9%.

Markets do not yet fully understand the implications for a slowing China. High growth in China has been a constant for the last 30+ years. It's a big change for the global economy to swallow.

I think the reality is that China's economy is simultaneously changing from an export-driven model to a consumption-driven one, while also dealing with a serious demographic problem (it's no coincidence they eased the one-child policy last year). You'd expect some hiccups when the world's second-largest economy goes through such a big structural transformation.

Is a Chinese market correction needed? I think so, and it looks like it's already well underway. That's natural, and not something to panic over. An economy can't grow forever at a constant rate, especially a double-digit rate. I see China's current problems as a normal growing pain, and short-to-medium term in nature.

The end of the near-zero interest-rate policy

The last big issue I see is the Fed finally raising the Federal Funds rate from its 0% target to a 0.25% target. The market has waited for this moment with great trepidation for several years now. Every time the markets got wind of a rate hike over the past two years, the major indices spiked lower.

Taking a step back, though, I think the market's fear is not driven by economic fundamentals. Inflation is well in check, the labor market is looking better and better, and GDP keeps on trucking slowly, but surely. Fundamentally, raising rates is a good thing -- it means that the economy is healthy enough to not need all this central bank assistance anymore. After eight years of a very dovish and accommodative stance, I think Yellen and Co. would be hard-pressed to raise rates unless they were supremely confident the economy could handle it.

In practical terms, December's rate hike was more symbolic than anything else. The jump from 0% to 0.25% is teeny tiny.

The bigger challenge for the Fed is managing expectations and group psychology. There are mega-sized investment funds trading everyday with borrowed money that carries a next-to-zero interest rate. They're playing with free money, essentially. These funds are looking at a future with higher rates and asking themselves, "What are we going to do without this free money to juice our returns?"

The broad concern is that, in a higher-rate future, these big players will sell their equity positions and put their capital in other asset classes. If that happens, the big-money selling would drive down stock prices. It's simple supply and demand. This is the "equity asset bubble" you'll hear about in the financial media.

I think there is a legitimate concern with this argument, and it's also true that higher rates will be a headwind to business investment, lending, and all the other credit-related economics that make the world turn. For example, the dollar has been strengthening against global currencies over the past 18 months as investors have been anticipating the rate hike. The strong dollar is hurting U.S. exports, and will probably start to show some impact on the bottom line for international megacorps that sell overseas

If profits dip at these companies, that could spook the market, and trigger a sell-off. That would be another short-term problem. As the economy continues to grow, the natural rhythm of interest rates and currency markets will eventually find balance, making the current issue a short-term hiccup on the long-term growth trend.

Again, this is not a big deal if your time horizon is more than a year or three.

These three reasons are a perfect storm for short-term fear

What does all that mean in terms of the S&P 500 dropping 10%+ thus far in 2016? I think that low oil prices have forced certain big-money funds to sell off equity positions, and that, coupled with the bad headlines from China and the concern over higher interest rates, combined to form the perfect storm. Markets tumbled, and fear replaced reason.

For example, Art Cashin, Director of Floor Operations at UBS, reported this month that large sovereign wealth funds have been forced to sell stocks because of the losses they are taking on the commodities and currency sides of their portfolios. He also reported rumors from the trading floor that hedge funds are doing the same thing -- selling their stocks to cover losses from their oil and gas speculative bets. Once the selling started, Cashin reckoned that automated trading systems likely triggered even more selling as their algorithms struggled to understand why the market was falling.

All of these drivers are mechanical, and don't reflect any underlying economic fundamentals other than the low oil prices that triggered some speculative losses. Should you panic because some hedge funds made bad bets on oil prices? I wouldn't, for what it's worth. None of these machinations should cause a major problem for the U.S. economy, broadly speaking.

The prospect of a U.S. recession, and what that means for your investing today

Could the U.S. be on the verge of a recession? Maybe. But who knows, really. It's been eight years since the last recession, which is a little bit longer that the average time between contractions since World War II. Based on history, the next recession will probably come sooner rather than later.

If the U.S. does dip into a recession, it shouldn't be a surprise by historical standards, and it also shouldn't cause panic. The economy will always have periods of contraction; it's a normal part of doing business.

U.S. Unemployment Rate data by YCharts.

For now, the economy fundamentally looks OK. The labor market keeps improving, albeit slowly, and the longer-term view of GDP is still in the "new normal" range.

If your time horizon is more than just a few years, I wouldn't worry. Before the financial crisis, the S&P peaked in the middle of 2007, at around 1,600. It got back to that pre-crash high around the beginning of 2013, five years later. Today, even after the market has fallen 10%+ so far this year, we're still over 15% above the 2007 high.

These returns since that 2007 peak aren't winning any awards, but they're still better than many other asset classes over the same period. The Case-Shiller Composite 20 Home Price Index is still 10% below where it was when it peaked in 2006, for example.

Case-Shiller Home Price Index: Composite 20 data by YCharts.

It's easy to forget in a fearful time that the S&P 500, by historical standards, is still knocking on the door of all-time highs. Since 2010, the market has been on an absolute tear, and it wouldn't be a horribly bad thing if the market did pause for a short-term correction. That's the way the markets have always worked, and there's no reason to think anything has changed now.

There's fear in the markets right now, but that fear is not based on anything scary for a long-term investor. If your investment horizon is longer than just a few months or a couple of years, I don't think you should be worried. If anything, today's fear may be your entry signal.