Image source: Getty Images.

It may not get the same recognition as Social Security, which puts income in the pockets of retired workers on a monthly basis, but Medicare's importance is rapidly growing for the roughly 56 million people who are eligible to receive Medicare. Of these eligible people, approximately five in six are seniors aged 65 and up.

Medicare's importance is growing

According to a report published by the Urban Institute in September 2015, a male with average lifetime earnings who turns 65 in 2015 will receive an estimated $195,000 in lifetime benefits from Medicare, net of premiums. By comparison, the same individual is expected to receive $294,000 in lifetime benefits from Social Security. However, based on Urban Institute's far-looking projections, by 2055 the average-earning male turning 65 will receive a larger lifetime benefit from Medicare ($501,000) than from Social Security ($496,000). Medicare is growing in importance for seniors, and in just a few generations, it could prove more important than Social Security.

Unfortunately, Medicare shares the same issue as its peer program, Social Security: Its spare cash will soon be depleted.

Image source: Getty Images.

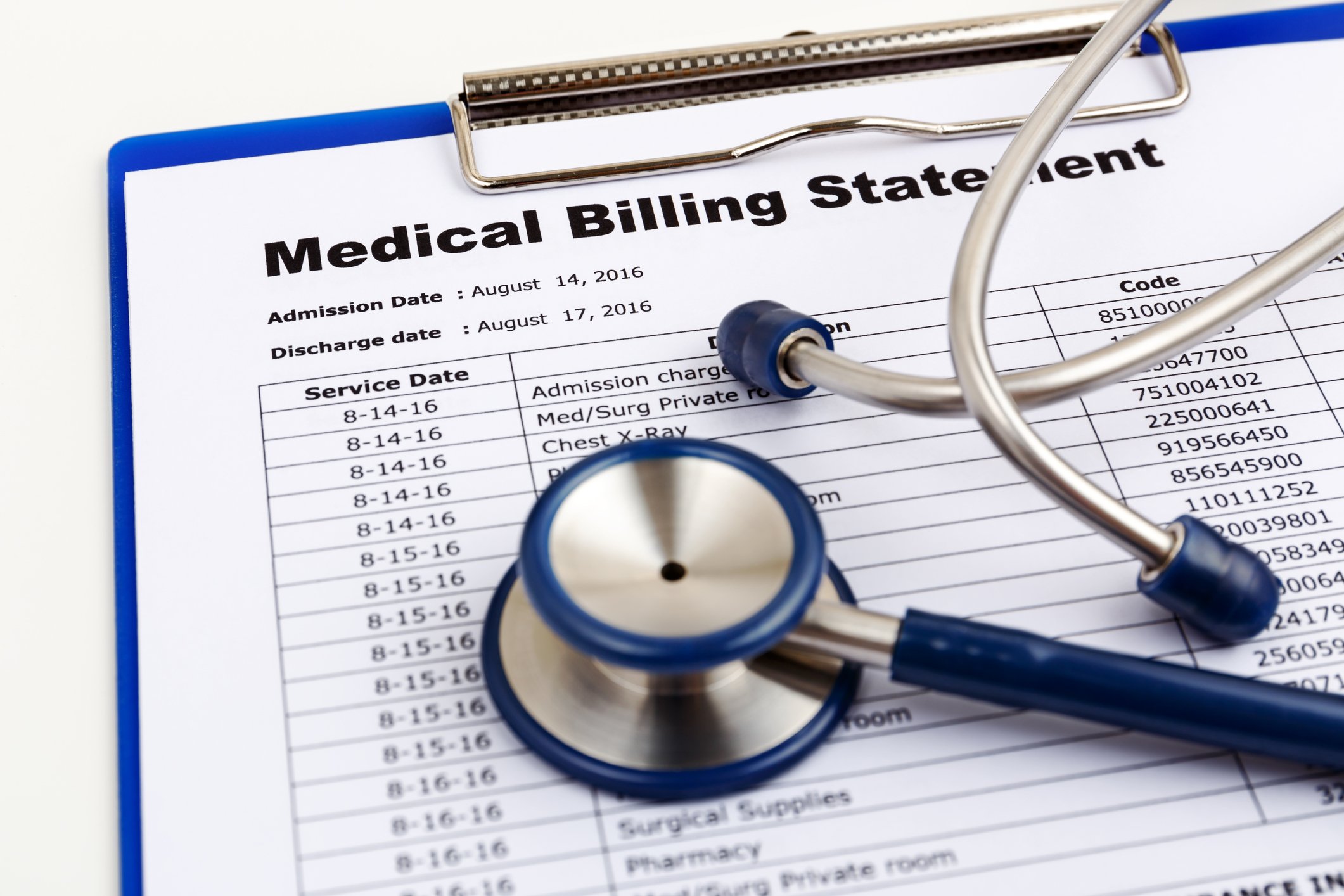

According to the Medicare Trustees Report for 2016, the Hospital Insurance Trust is expected to exhaust its spare cash by the year 2028. Should this excess cash be depleted, reimbursements to hospitals and physicians could drop by 13% as Medicare essentially becomes a budget-neutral program that pays out only what it receives in revenue. It's a terrifying forecast for a program that's become so vital to the financial and physical well-being of senior citizens.

But before we can even think about fixing Medicare's Hospital Insurance Trust budgetary shortfall, we should understand how the program is funded in the first place, so let's take a closer look.

How Medicare is funded

To understand how Medicare is funded, we first have to recognize how its three working parts obtain their annual revenue. Medicare's three critical components are Part A (hospital insurance and long-term skilled nursing care), Part B (outpatient services), and Part D (prescription drug plans). In 2014, Medicare revenue totaled just shy of $600 billion, with $261 billion being spent on Part A, $260 billion spent on Part B, and $78 billion on Part D.

Image source: Getty Images.

Part A

Here's the funding breakdown for Part A, with data courtesy of the Kaiser Family Foundation:

- Payroll taxes: 87%

- Taxation of Social Security benefits: 7%

- Interest: 3%

- Premiums: 1%

- General revenue: 1%

- Other: 1%

As you can see, payroll taxes provide the vast majority of funding for Part A. The Medicare portion of taxation involves a flat 1.45% tax on all earned income for working Americans, assuming they're employed by someone else. If they're self-employed, workers are responsible for the entire 2.9% Medicare tax to fund the Hospital Insurance Trust.

However, as part of the Affordable Care Act, there's also a Medicare surcharge tax of 0.9% that applies to employees who earn more than $200,000 in income. This 2.35% Medicare tax rate kicks in once an individual's income crosses the $200,000 barrier. Prior to that point, they would owe 1.45% on earned income like everyone else.

Note also that just 1% of funding comes from Part A premiums. The reason is that anyone who's earned 40 lifetime work credits qualifies to receive Part A with no monthly premium. Only people who've not earned 40 lifetime work credits are typically required to pay a Part A premium.

Image source: Getty Images.

Part B

Next, we'll take a look at the funding breakdown for Part B, which covers various outpatient services:

- General revenue: 73%

- Premiums: 25%

- Interest: 1%

- Other: 1%

You'll quickly see that Part B is funded very differently than Part A. General revenue, which is money that's primarily derived from federal income taxes, makes up nearly three-quarters of the funding for Part B. The remainder is made up almost entirely of Part B premiums, which all enrolled members pay.

However, there can be quite a bifurcation in monthly Part B premiums costs. For instance, longtime Medicare enrollees who are also enrolled in Social Security have their monthly Medicare premiums automatically deducted from their Social Security benefits. This group of individuals, which makes up about 70% of Medicare beneficiaries, is also protected by a clause known as "hold harmless." The hold harmless clause ensures that Part B premiums don't rise at a quicker rate than Social Security's cost-of-living adjustments. With no COLA in 2016 and just 0.3% in 2017, many seniors will be paying just a fraction more for their Part B premiums in 2017.

On the other hand, new enrollees to Medicare, persons who aren't enrolled in Social Security, and those who choose to be billed directly are set to face a monthly Part B premium that's risen about 15% year over year. This remaining 30% of Medicare enrollees often faces the bulk of annual price increases in Part B.

It's also worth noting that members with high incomes -- in excess of $85,000 for individual filers and $170,000 for joint filers -- pay a surcharge on their Part B premiums.

Part D

Finally, Part D, the prescription drug plan, relies on a somewhat similar breakdown as Part B for its revenue:

- General revenue: 74%

- Premiums: 15%

- State payments for dual eligible people: 11%

Image source: Getty Images.

A majority of Part D's funding comes from federal revenue, while a slightly smaller portion than Part B is derived from the premiums consumers pay. Also like Part B, high-income taxpayers with more than $85,000 in annual income, or $170,000 in joint-filing income, owe a Part D premium surcharge.

The big difference in Part D is the 11% of funding that comes from a small percentage of the population that qualifies for both Medicare and Medicaid (aka the "dual eligibles"). State Medicaid agencies have an obligation to pay Medicare cost sharing for most dual eligibles, and in most cases providers are prohibited from charging dual-eligible consumers for prescription drug costs.

Tying it all together

Here's what all three components of Medicare look like when they're melded together (figures don't add to 100% due to rounding):

- General revenue: 41%

- Payroll taxes: 38%

- Premiums: 13%

- Taxation of Social Security benefits: 3%

- Interest: 2%

- State payments from dual-eligible people: 1%

- Other: 1%

Image source: Getty Images.

As you can see, federal income tax revenue is the most critical component of Medicare funding, but the Medicare tax working Americans pay into the system is a very close second. Furthermore, it's worth pointing out that whereas Social Security derived 10% of its annual income from interest in 2015, Medicare generated only 2% of its annual revenue from interest in 2014.

With Medicare set to burn through its excess cash by 2028, the most effective way to tackle its impending budgetary shortfall could be to raise payroll taxes. According to the Medicare Board of Trustees report, the long-term actuarial deficit in the program is 0.73%. In layman's terms, it means the 2.9% cumulative tax in Medicare would need to be raised to 3.63% to eliminate any shortfall. Since this total is often split down the middle between employers and employees, we're talking about a 0.365% tax increase to the average working American.

While President Donald Trump has stated his unwillingness to alter Social Security or Medicare, change will more than likely be coming to the program at some point over the next decade.