You may hear economists and commentators on financial news networks referring to the purchasing power of money. While it sounds like a pretty straightforward concept, there are actually some big economic and personal finance implications when it comes to how much purchasing power your money has.

Definition

What is purchasing power?

The purchasing power of money is the amount of goods or services that can be purchased with a certain amount of money at a certain time. For example, if you have $20 and a gallon of gas costs $4, the purchasing power of that $20 is five gallons of gasoline.

Having said that, purchasing power is more often used as a general financial concept, as opposed to how much of a specific item you can buy. For example, you might hear about the purchasing power of the average American's annual salary, or how far $1 million in retirement savings will go.

Inflation

Inflation and purchasing power

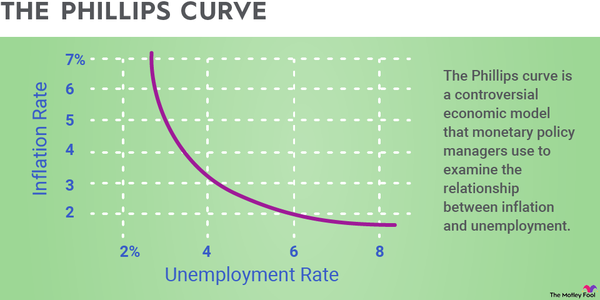

Purchasing power is closely related to the concept of inflation. In fact, the two have an inverse relationship. Inflation reduces the purchasing power of money over time.

As an example, let's say that a loaf of bread costs $2.00. If we have an inflation rate of 3% over time (roughly the long-term average in the United States), this means that the cost of a loaf of bread can be expected to be about $2.69 in 10 years. Currently, a $10 bill has the purchasing power to buy five loaves of bread. But in 10 years, the same $10 is likely to not be enough to buy four.

Why it matters

Why purchasing power is important in investing and saving

One of the central goals of investing is to achieve real returns -- that is, investment returns beyond the rate of inflation. In other words, you want the purchasing power of your money to increase over time, not be eroded by investing.

This is why putting money in a savings account (instead of investing in stocks, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), mutual funds, bonds, etc.) can be dangerous over the long run. Think of it this way. If the average inflation rate is 3% per year and your savings account pays you 2% interest on average, you're actually losing purchasing power over time. On the other hand, if you invest in an S&P 500 index fund, which has historically returned 9% to 10% annually over the long run, you're likely to keep pace with inflation and more.

Related investing topics

Example

Example of purchasing power of money

Let's say that you're 40 and want to retire at age 65 with $1 million. But you're thinking of this in the context of today's purchasing power of $1 million. In other words, what you can buy with $1 million today and what you'll be able to buy with $1 million in 25 years when you retire are likely to be two very different things.

So, we can use a hypothetical long-term inflation rate to figure out how much you're likely to need in 25 years to provide yourself with a "million-dollar retirement" in today's context. For example, $1 million compounded at a 3% annual inflation rate shows that you'll need to have about $2.09 million when you reach age 65 to have the same purchasing power of $1 million today.

Of course, nobody can predict inflation with perfect accuracy, and the inflation rate can vary significantly from year to year. However, a 3% long-term inflation rate has historically been pretty close over periods of decades.