Netflix (NFLX +0.17%) is up to its elbows with Verizon (VZ 2.00%) trouble.

The old "Loading, please wait" notification in stalled Netflix streams are getting replaced by more specific notices about cramped networks, and Verizon was the first service provider to get called out. Big Red served Netflix with a cease-and-desist order, threatening legal action. Netflix said it was just providing more transparency for its users and continues to offer more detailed information.

What does this squabble mean for regular users? Let's look at how the digital video system works.

Follow the money

On the publishing end, Netflix sends digital video data to consumers. Netflix is paying for its bandwidth, and sometimes pays a bit more for high-quality feeds with fewer middlemen. Comcast (CMCSA 1.58%) is the classic example of this, but Netflix is also sending checks directly to Verizon these days.

On the consumer side, I'm paying Verizon top dollar for a reasonably fast connection to the rest of the Internet. Keep this fact in mind.

So there might be cases where slow Netflix connections are caused by the steps in between. At the handover from your local service provider's city-wide network to the long-haul Internet backbone. Or where that backbone connects back to a data center that hosts Netflix content. Maybe even inside that data center, where the pipeline to the rest of the world doesn't always have a straight shot to those Netflix videos.

Any or all of these hand offs may involve two companies that have worked out some sort of agreement on how to handle data transfers. For example, my path to viewing Netflix videos jumps from the local Verizon network to a Verizon-owned Alert.net link that drops me off in Miami. At the NAP of the Americas data hub, Alter.net hands it off to TeliaSonera at the door. Then it's time to reach a Netflix server in the building, and Telia doesn't own that one.

NAP of the Americas, an imposing city block in Miami that's packed to the rafters with servers and networking gear. Image source: Verizon Terremark.

The last few steps is where it gets complicated.

-

Who's paying who for what?

-

Who's responsible for building the networking infrastructure that makes it all happen?

-

Who's paying that bill?

In some cases, it gets down to how the network-building costs can get passed down to either consumers or content pushers -- maybe even both.

In the specific case of Netflix traffic to Verizon customers, Big Red already collects payments on both ends. Netflix-and-Verizon customers like myself expect a smooth connection in which Verizon itself doesn't become a bottleneck.

Many websites and online services fall far short of saturating my Verizon pipe, because their servers are simply not set up for high-speed data feeds direct to consumers. Netflix is not one of these, being among the Internet's highest-traffic content publishers that also pays extra for that special Verizon link-up. Indeed, the company runs its own content delivery network, with nodes sprinkled across the map, and will happily provide expertise and specialized hardware for free to ensure smooth video delivery.

So I'm paying for performance that even the highest-quality Netflix stream simply cannot saturate. Netflix is paying top dollar for high-speed services on the other side, including a direct connection agreement with Verizon itself. Money is flowing to Verizon from both ends ... and I still get network congestion in the middle of my House episodes.

But, but ... network equipment is expensive!

Let's be clear: It's not cheap to build, maintain, and operate a high-quality data network. That's especially true for networks spanning the continent, or in rare cases the entire planet.

But Verizon, Comcast, and other broadband providers knew this when they chose to pursue the Internet service business. And they're making a killing on broadband services.

Verizon sees FiOS fiber-optic Internet services as a growth opportunity for the long haul. FiOS helped Verizon's wireline division increase its operating income by 19% last year, even as copper-based voice and DSL subscribers continued to sign off by the busload. Fifteen percent of Verizon's DSL customers either switched to FiOS or left the company altogether last year.

The story is similar at other large-scale Internet service providers. Broadband is the name of the game, and often the best path toward sustainable growth.

Sounds like a business operation worthy of serious capital investments, right?

Unfortunately, that theory only works if Verizon faces serious competition in its end markets. But that's not the case. Not at all.

Well, how bad is it?

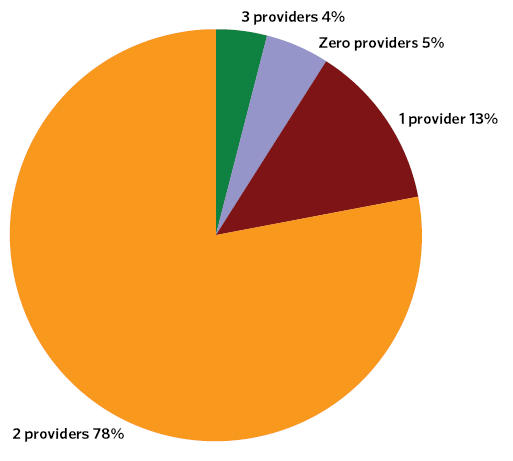

In most markets, American consumers must choose between the incumbent cable company or the dominant telecom in the area. A recent government report showed that 96% of Americans have at most two hardwired service options available. Most of the time, it's an uneven matchup between high-speed fiber (could be cable or phone wires) or sluggish copper (again, could go either way). "Whether sufficient competition exists is unclear and, even if such competition presently exists, it is surely fragile," the National Broadband Plan report says.

Source: National Broadband Plan.

Comcast CEO Brian Roberts doesn't deny this lack of competition. Speaking at a recent industry conference, Roberts explained that he doesn't compete with the second-largest cable provider at all.

"We don't compete with Time Warner Cable (NYSE: TWC)," Roberts said. "We have to start with that very fundamental point. They're in New York, we're in Philadelphia. They're in L.A., we're in San Francisco. You can't buy from Comcast in New York; You can't buy Time Warner in Philadelphia."

Of course, Roberts was trying to point out how his company's proposed merger with Time Warner won't lead to reduced competition. But the point stands across the two industries -- If you have more than one cable provider or more than one telecom option where you live, you're one of the lucky few. Moreover, Verizon will never cover its entire service area in FiOS goodness -- because that would mean competing against honest-to-goodness high-speed cable options in some markets.

These territories are as gerrymandered and separated as possible. Local monopolies on a national scale.

Competition is simply not an issue.

What it all boils down to

Which is why, say, Verizon isn't overly worried about disappointing its own customers with sluggish Netflix streams. In nearly every case, consumers just don't have any better options available. Where FiOS exists, the local cable monopoly is probably slow, expensive, or both. You can abuse a captive audience.

So Verizon has no incentive to provide excellent service. Not to Netflix, not to consumers, not to anybody. "Good enough" will do, even when it really isn't good enough. Why improve your network when you can get away with just pocketing the upgrade budget as profit?

This is what Netflix is raging against. The protest may not always be as clear as possible, and the larger points of a consumer-hostile competition policy can get lost in network neutrality noise.

On a more detailed scale, Verizon gets to say that Netflix is unfair when it isn't exactly the Verizon network that's at fault -- it's the connection between Verizon and the rest of the world, or some other link along the way between servers and video watchers. But it still comes down to Verizon's policies and choices, and every "buffering, please wait" prompt ultimately leads back to Big Red. Or to Comcast, or Time Warner, or whichever provider you might use.

In other words, Verizon has every reason to tell Netflix to shut up. The video service might run better if we decided to tune up our networks, but it's just cheaper to sweep congested connections under the rug. Nothing to see here, please move along.

And don't ask us to deliver the service you're actually paying for, on both ends of the connection.