For more crisp and insightful business and economic news, subscribe to The Daily Upside newsletter. It's completely free and we guarantee you'll learn something new every day.

Three years ago this week, U.S. energy prices collapsed as the pandemic triggered arguably the swiftest economic downturn the world has ever seen.

It now feels like eons ago, but you will surely remember: Sheltering in place. Lining up for toilet paper. Fighting over canned food in grocery store aisles like wildebeests. It was wartime, only our enemy was a virus, not another country. And this was a foe we could not see.

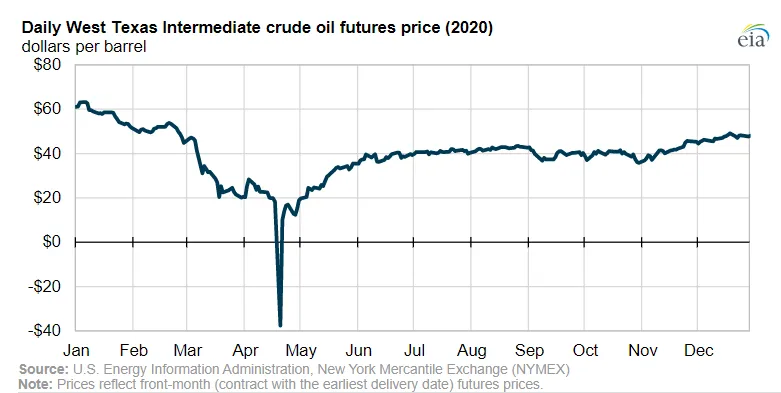

On Wall Street, energy prices across the board took a nosedive as economic activity came to a near-standstill. But none of those prices did what U.S. crude oil futures did – the cornerstone of the global energy market – when they fell below zero.

In the history of the world, this had never happened before, and it's not happened since.

The very first crude oil contract traded below zero at 2:08 p.m. ET on Monday, April 20, 2020. Traders, for those who don't already know this, tend to be very nostalgic about major market moves, particularly if they are responsible for them, so I have little doubt there is someone out there who kept their receipt of the world's first-ever zero oil trade as a memento for themselves. Perhaps we will find out who they are one day.

As soon as barrels of oil exchanged hands at zero, it touched off a firestorm. Over what became the final 21 minutes of frantic trading that day, traders around the world leapt into the abyss of subzero oil trading, driving oil prices to a never-before-seen nadir.

In the end, U.S. crude oil futures traded continuously lower until they hit negative $40.32 a barrel, the lowest intraday handle ever recorded by the most heavily traded energy contract in the world. Prices settled at negative $37.63 a barrel.

Many traders who bought oil at zero believing it would be an automatically winning trade, soon learned differently. "I am sure a lot of people thought, 'If I buy at zero, what can I lose from that?'" one big-name energy trader told me at the time. "Well, it turns out you can lose over $40 a barrel."

Traders who did not know any better lost millions that day. Unlike with the stock market, where, for the most part, the worst that can happen to you is losing your entire investment and any gains from it, futures trading runs the risk of infinite losses, as prices can go up – or down – without limit.

Fortunes were won and lost. Traders furiously burned up the phone lines speculating what would happen next. President Donald J. Trump, still in the White House, frantically called his chief economic advisor, CNBC's Larry Kudlow, to explain to him what was going on. (I have never told this story: One of my sources said Kudlow called him that afternoon, begging for an explanation as to what was happening and what he should tell the president.)

Tabulating the damage, a total of 14,913 crude oil futures contracts traded at negative prices that day. On average, sellers were so desperate to get oil barrels off their hands that they paid buyers to take it from them (instead of the other way around) at a rate of more than 30 million gallons a minute. Why? Because storing oil is very expensive. If demand for oil evaporates, it is nearly impossible to recoup your expenses if you can't sell it at a premium.

Immediately afterward, the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), the watchdog to the nation's futures market, proclaimed it would be "watching these markets closely," but didn't offer much of a solution.

Terrence Duffy, chairman and chief executive of the CME Group, the Chicago-based parent company of the New York Mercantile Exchange, where U.S. crude oil is traded, appeared on television with some choice words for traders. "Futures contracts have been around for hundreds of years, and I will tell you, since Day 1, everybody knows that it's unlimited losses in futures," he said. "So, nobody should be under the perception that it can't go below zero."

His remarks left many market participants financially destroyed by the events of April 2020 with the distinct impression that their losses were solely their own fault.

Yet an examination of the CME's anonymized, tick-by-tick trading data shows traders piled on to liquidate larger positions as oil prices crossed the zero mark. As a self-regulatory organization, the CME had a responsibility to be closely troubleshooting to protect market participants.

To this day, the CME, which has access to real-time, non-public trading information in its markets, has remained silent on whether it believes any one group of commodities traders was responsible for the bottom falling out of West Texas Intermediate light, sweet crude oil futures -- what it calls "the most important commodity contract on the planet."

Meanwhile, the CME's government regulator, the CFTC, released an interim report in late 2020, but it was utterly inconclusive.

In sum, those in charge of overseeing the U.S. energy market did not offer a clear explanation to the public, who also were rattled by whipsawing prices.

Toothless regulation has long been an issue in the nation's Rabelaisian energy markets, but even those within the CFTC's own ranks blasted the agency's response as "incomplete and inadequate."

Enter Robert Mish, a septuagenarian and rare coin expert, who was holding ten oil contracts as prices turned negative. Instead of taking the net loss of $92,490 when he sold his position April 20, Mish filed a class action lawsuit – which, three years on, is slowly heading for trial.

The lawsuit, spearheaded by Mish's Menlo Park, Calif., trading company, Mish International Monetary Inc., accuses a small group of London traders at Vega Capital London Ltd. of manipulating U.S. oil prices – and profiting off it to the tune of more than $600 million.

Since the case was filed in 2020, the traders in question, who deny they were to blame, have been boldly featured on the pages of the London tabloids splurging on Ferraris, mansions, race car hobbies, art galleries – and even starting up an international polo team.

The British press have dubbed the group "the Essex Boys," in a nod to the fact that many of them traded from London's outlying county of Essex.

According to lawsuit filings, reviewed by Power Corridor, the London-based traders "built up substantial net selling pressure" in the U.S. oil market, then "engaged in a frenzy of selling, which greatly increased their sales per minute and caused their percentage of the entire market's sales to exceed 30 percent in this worldwide market."

How would this allow them to profit? The suit goes on to explain that by placing automatic trades to buy crude oil at the market's settlement – priced at more than $30 a barrel below zero that day – the traders were, in effect, getting paid to take the oil contracts, earning hundreds of millions of dollars. If the contracts had instead continued to be priced in positive territory at settlement, the London traders would have had to pay for them.

In all, the London traders sold 16,205 U.S. crude oil contracts, while getting paid to take 16,268 contracts at the negative settlement price notched April 20 – profiting enormously from both and realizing a single-day profit of $632,814,390, according to the legal filings.

Market manipulation suits are notoriously challenging to prove, as the plaintiff must show "scienter," defined by the U.S. Supreme Court as "a mental state embracing intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud." Reckless or highly unreasonable conduct representing an extreme departure from the standards of ordinary care may also satisfy the scienter requirement.

In seeking to prove this, the Mish lawsuit cites private communications among the London traders "in which they coordinate trades" and "track what one another was doing," with the alleged goal of hammering oil's settlement price, resulting in their outsized profit.

Details of the lawsuit are jaw-dropping. Internal messages among the London traders belonging to a WhatsApp group called "Legends XXX" appear to show them egging each other on. "Just keep selling it every 5 points," one of the messages said. "You just got to keep selling," another urged. "Everyone is going to be short and have ammo," said another. One message read, "F--ing mental. I wanna' see negative WTI [West Texas Intermediate] prices."

After the sell-off, a trader wrote, "We pushed each other so hard for years for this one moment...And we f--ing blitzed it boys."

One trader also warned the group, "Please don't tell anyone what happened today, lads."

According to the suit, between 96.2 percent and 99.7 percent of the traders' trades were strongly correlated with one another, moving virtually in lockstep "in the same direction at the very same time."

U.S. district judge Gary Feinerman wrote in an order, "The content of their communications, along with the high degree of correlative trading among most of them, give rise to a highly plausible inference of an agreement among them."

Following the April 20 trading coup, the UK brokerage firm G.H. Financials Ltd., a clearinghouse that held the London traders' positions at Vega Capital, dropped Vega as a customer, noting the trades "set off multiple market alarms," according to the legal filings and press reports.

After repeated motions by the defendants to dismiss the complaint, Judge Feinerman ruled late last year that 10 of the 12 traders who stood accused would go on to trial, in addition to Vega Capital and its owner, Adrian Spires.

The traders' names, which previously had been concealed in court filings, have been unsealed: Paul Commins and his son, George Commins; Christopher Roase; Elliott Pickering; Aristos Demetriou; Connor Younger; James Biagioni; Henry Lunn; Paul Sutton; and Matthew Rhys Thompson.

The traders, as well as their firm, Vega Capital, and Spires, have vigorously defended themselves against the legal claims. "None of our clients did anything wrong by trading their own view of the market on April 20, 2020," said Evan Flowers, a lawyer at Dechert LLP in London, who represents the group of traders.

One of Mish's lawyers at Lovell Stewart Halebian Jacobson in New York told Power Corridor this week that the case will now move forward against 10 of the 12 accused traders, representing a near-total victory for Mish. But he added that the legal proceedings could stretch well into 2025 and beyond, as certifying the case as a class action is likely to be hotly contested.

It is not just Mish's case, but most market manipulation cases that tend to drag on interminably. One market manipulation case the firm is still working on dates back to 2012, the lawyer says.

What happens from here? Mish's case could go to trial – eventually – or it could be defeated by the London traders. Or it could settle. Either way, Mish is probably in for a long wait.

Whatever transpires, it should be noted that it is because of Mish, the rare coin dealer – and not U.S. regulators – that Americans and Wall Street investors have their best chance at learning why the nation's oil prices fell below zero.

Power Reads

Some of our favorite recent reads, for your weekend edification.

Why Fox News and Dominion Inked a Record Settlement

Neither side wanted to give in but, in the final analysis, Fox News and Dominion Voting Systems each had sacred cows they refused to slaughter. In this riveting report of the most expensive known defamation settlement in history, New York Times journalists Jeremy W. Peters, Jim Rutenberg and Katie Robertson reveal what mattered most to each side -- and why Fox News, when confronted with having to genuinely apologize for peddling lies about the 2020 U.S. presidential election or pay hundreds of millions of dollars, chose the latter.

How has DeSantis really governed Florida?

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has become a caricature of himself, even before making any grand announcements to run for president in 2024. But while he's starting up culture wars and fighting over banning books, transgender policies and immigration issues, what is he actually doing for the residents of Florida? Shouldn't we know if he wants to be our nation's next president? Author and journalist William Kleinknecht decides to find out. An excellent essay from Time pulling back the curtain on the human behind the chocolate-pudding-scarfing cartoon character.

Strategic breeding by 'elites' raises some old, thorny questions

The premise is simple enough: Many Americans don't feel they are able to have as many children as they would like to. There is a long list of reasons, from the unaffordability of child care (and life in general) to work demands making it increasingly harder to rear a healthy brood. And let's not even get into concerns about climate change and fears among younger generations of a dystopian future. But what to do about it? This is where it gets complicated. And not a little bit troubling. British journalist Io Dodds takes a closer look at a quiet trend that's been revisited for centuries, but has yet to be mastered.

*Power Corridor is the newest publication from The Daily Upside. Delivered twice weekly, Lead Editor Leah McGrath Goodman gives readers a unique view into the interplay between Wall Street and Washington. Sign up for free here.*