For more crisp and insightful business and economic news, subscribe to The Daily Upside newsletter. It's completely free and we guarantee you'll learn something new every day.

A high-stakes meeting was held in July at the headquarters of the United Nations' International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Jamaica. Countries were arguing over whether mining companies should be allowed to start reaping rare earth minerals 5,000 meters (just over three miles) under the ocean's surface. The clock was ticking. A legal loophole discovered by Canadian mining business The Metals Company, in partnership with the Micronesian island nation of Nauru, meant that the ISA was supposed to decide how companies could get cracking on deep sea mining that same month.

While some nations, including China and Norway, were keen to commence open season in the deep sea, others, like Germany and France, fought for a moratorium, arguing it could cause untold ecological damage. In the end, they managed to delay the decision until the next ISA board meeting in July 2024, but the countries anxious to start mining are unlikely to sit on their shovels until then.

So, pop your scuba suit on as we dive into the murky waters of deep sea mining.

Potato Farming

The minerals at issue come in the form of potato-sized nodules scattered along the deep seafloor. Dr. Helen Czerski, a physicist and oceanographer at University College London, told The Daily Upside that the nodules take millions of years to form as sediment drifting down through the ocean at an unbelievably slow pace accumulates around objects like bits of bone and sharks' teeth. "A nodule the size of your fist has taken around 2 million years to grow," she said.

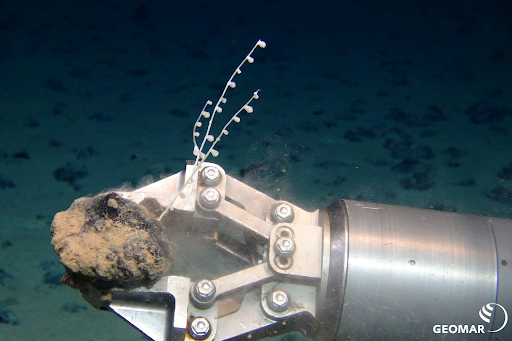

Mining companies want to collect these nodules using machines that are lowered onto the seabed and then crawl along the seafloor hoovering up the nodules. The metals contained within these precious potatoes -- like cobalt, nickel, and manganese -- are crucial to building batteries, so mining companies argue that deep sea mining is essential to manufacturing electric vehicles and, therefore, to the future green economy.

Nations already have authority to grant sea mining licenses in their waters, but large tracts of seabed don't belong to any one country, and they hold an untapped reserve of nodules, as the metallic potatoes only form at depths of more than 3 kilometers.

(Photo credit: ROV-Team/GEOMAR under CC BY 4.0)

Divvying Up the Sea

In 1982, the UN introduced the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to safeguard mankind's common heritage over the oceans. The conventions established which parts of the sea belonged to specific countries, and which parts were shared by the world. Economist Guy Standing, author of the book The Blue Commons: Rescuing the Economy of the Sea, told The Daily Upside that the convention ended up as a "messy set of compromises."

Every country with a coastline was granted ownership of 200 nautical miles from their coast -- a system which disproportionately benefited former colonial powers:

- France was granted the largest swath of ocean to various islands it claims to own that are left over from its colonial past, receiving 12.7 million square kilometers.

- The US, by comparison, was apportioned 12.4 million square kilometers.

- The UK received 6.8 million square kilometers of ocean, an area 27 times larger than the island of Britain itself. "It was a neo-colonial trick, really," Standing said.

These areas are known as exclusive economic zones. Beyond them, the sea is not owned by anyone. The ISA regulates mining outside the economic zones and set up a mechanism so that any finanical benefits that came from deep sea mining outside EEZs would be shared among the countries of the world -- including those without a coastline.

China's White Whale: Despite its size, China was granted only 900,000 square kilometers of seabed under UNCLOS, a fact that remains a source of tension as China is now one of the countries leading the charge for deep sea mining. As a result, Beijing has slightly changed its tune. While China lobbied in favor of a sharing mechanism in the 1980s, in July it resisted a call from 45 African nations to impose a blanket 45% levy on deep sea mining activities. "The China of today is a very different proposition from the China of 1982," Standing observed.

License and Registration, Please

While companies are not supposed to mine outside the exclusive economic zones just yet, that doesn't mean they have to stay out entirely. The ISA granted 31 "exploration licenses" to companies, and according to Standing, the line between exploration and outright mining is fairly fuzzy. The Metals Company, a frontrunner in the race to start commercial mining, raised 3,600 tons of nodules in the three months leading up to the end of 2022, Standing said. "3,600 tons is a lot, you can make a lot of money from that."

20,000 Leagues Underfunded: Standing argues that the ISA doesn't have enough power to regulate the companies that want to get a crack at the undersea minerals, partly because of a budget that's just $10 million per year. To put that into perspective, every license that the ISA grants comes with a $500,000 payment from the applying company -- a cash injection equivalent to 5% of the regulator's annual budget. He added that the ISA doesn't have deep enough pockets to conduct its own ecological assessments, meaning it's reliant on the good faith of mining companies to submit their own impact reports.

Last October, the ISA investigated a sediment plume by a subsidiary of The Metals Company. While it said the accident did not breach ISA rules, it did criticize the company for failing to meet its own risk management procedures.

The exact ecological impact of a sediment plume is hard to know at this stage, Dr. Czerski said. What's certain is that mining in the deep sea is quite different from mining in more coastal waters -- and the ecosystems there are vastly different. "These environments are incredibly calm for these nodules to form," she said, adding that the wildlife in the deep sea is extremely diverse, highly specialized, and not at all used to sudden changes. "These nodules [...] they've been there for literally millions of years, just sitting there not doing very much. And so it only takes a little bit of sediment to completely cover that over, and then your habitat is completely different," she added.

Mushy Stuff: Metallic nodules are not the only resource that might ratchet up geopolitical tensions. The next big gold rush could be marine genetic resources. "The sea contains vast amounts of organisms that can be used for technological breakthroughs; in medicines, in chemicals in many, many ways," Standing said, adding that 13,000 organism-related patents have been filed since the UNCLOS mandate.

"Potentially, those patents are mind-blowingly profitable," he said. Three countries own the rights to 76% of patents filed: Germany, the US, and Japan. So buckle up, fighting over the high seas could get even more dramatic.