I’ve often said there’s only one way to make accounting interesting: when it is finance in disguise.

In accounting, cash outflows for big asset purchases are called capital expenditures. Many business owners will determine if they can service the debt for the purchase and whether they think they’re getting a good deal before making the purchase.

When we bring finance into the equation, we get capital budgeting. In this article, we’ll go over the most frequently used methods for capital budgeting and a few best practices to keep in mind the next time you need to make a capital expenditure.

Overview: What is capital budgeting?

Most business owners are familiar with a typical business budget. You project revenue for the year and itemize the operating expenses it will take to reach that number.

Capital budgeting analysis is done for more specific instances where you need to budget for big investments, such as the purchase of new equipment or a new line of merchandise.

Capital budgeting decisions are not based solely on whether the capital investment will be profitable, but on whether it will be more profitable than the opportunity cost of making the investment now.

Types of capital budgeting methods

The first three capital budgeting methods we’ll go over build on each other and can be used sequentially. We’ll use the same example project and look at how to capital budget for it using each of the three types.

Mike’s Marvelous Merry-Go-Rounds is considering purchasing its 12th merry-go-round to install at a park. The new merry-go-round will cost $800,000 to purchase and produce cash flows of $250,000 per year.

Type 1: Payback period

The payback period of an investment is the time it takes to earn back the initial cash outflow. The payback period method is typically used by startup and fast growing businesses.

They need to know how long it will take to recoup the cash laid out for an investment so they can plow that cash into new investments. Mike’s time horizon for this investment is five years, so if the payback period is less than that, it passes this test.

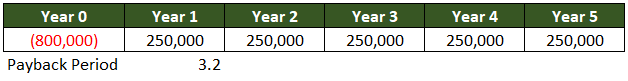

At $250,000 per year, it takes 3.2 years to recoup the initial investment. Image source: Author

In this example, the cash flow is the same each year, so the formula, 800,000 / 250,000, is easy. With uneven cash flows, calculate the cash flows after each year until you get to the correct number.

The payback decision rule tells Mike to move forward to the next method because the payback period of 3.2 years is less than his 5-year horizon.

Type 2: Internal rate of return (IRR)

The problem with using the payback period alone is that you don’t consider the time value of money. The principle of time value of money dictates that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in the future. Why? Because you can invest that dollar today to have more money later on.

The internal rate of return shows us the average annual return of the project. This number can ensure the project passes the time value of money test.

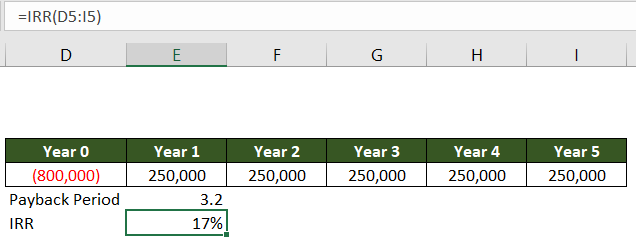

In Microsoft Excel, use the IRR formula to calculate the internal rate of return Image source: Author

For Mike’s project, the IRR is 17%. Compare this number to a hurdle rate, so called because the IRR must ‘hurdle’ it for the project to pass the test. A normal hurdle rate is somewhere around 12-15%, so Mike’s project passes the test.

Type 3: Net present value (NPV)

Taking it one step further, we calculate the net present value of the project. The NPV discounts cash flows by the same hurdle rate we compared the IRR to. It shows the total value of the project after all real and opportunity costs, which are represented by the discount rate.

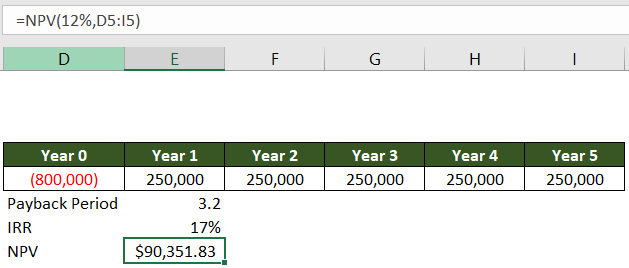

Use the NPV formula in Microsoft Excel to calculate net present value. Image source: Author

The NPV for the new merry-go-round, using 12% as the discount rate, is a respectable $90,351.83. Mike can make his investment knowing that projected cash flows provide a more than sufficient rate of return.

Capital budgeting best practices

Now that you know how the capital budgeting process works, here are a few best practices to remember.

1. Understand opportunity cost

The backbone of all finance is understanding opportunity cost. Every investment you make must be compared to what you could’ve earned if that money had been put to a different use.

This doesn’t mean you should fret about the differences in price between two brands of printer paper. However, when you make big investments, always keep opportunity cost in mind.

2. Don’t shoot from the hip

Constantly pursuing growth for its own sake will likely lead you to the poorhouse. Likewise, making knee-jerk decisions on expenditures that can make or break your business is a recipe for costly mistakes.

Carefully analyze all large investments to project revenue, expenses, and cash flow to determine if the project makes sense.

3. Always do autopsies

When I worked in the banking world, we analyzed big deals after the fact, in a process called the autopsy. Whether or not the deal worked out, we wanted to know what caused that result and how it compared to our projections going in.

Consider adding a cost category or department in your accounting software and tracking the actual cash flows related to the new investment. This is an easy bookkeeping change that will allow you to compare your projected numbers to reality and make better projections next time.

4. Consider using economic value added (EVA) analysis

Financial statements made using generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) do not include opportunity costs when calculating net income. There is an alternative approach, called economic value added (EVA), that does include these costs.

The formula is:

NOPAT - Invested Capital x WACC = EVA

We’ll go over each term and what the acronyms stand for individually.

Net operating profit after taxes (NOPAT) is your operating profit minus taxes paid. It is a way to remove other income and expenses from the calculation and focus on operations.

Invested capital is typically calculated as total assets - current liabilities. Capital includes all equity and the long-term debt used to finance the business.

Weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is the weighted average rate for debt and equity. Use the interest rate cost for debt and the hurdle rate established in the NPV section above to calculate the rate.

The EVA formula is effectively an NPV for the whole business. It discounts the income of the business by the opportunity cost of the investment from owners and debtholders. Applying this analysis to your business annually when you’re budgeting for the next year can help point you in the right direction.

Budget like the bourgeoisie

Now you’re prepared to whip out your spreadsheets and calculate a bunch of finance acronyms the next time you come across a big investment opportunity. Be conservative in your estimates, don’t forget about opportunity cost, and remember to do an autopsy of your projections after the fact.

Our Small Business Expert

We're firm believers in the Golden Rule, which is why editorial opinions are ours alone and have not been previously reviewed, approved, or endorsed by included advertisers. The Ascent does not cover all offers on the market. Editorial content from The Ascent is separate from The Motley Fool editorial content and is created by a different analyst team.