As we pass the halfway mark of 2017, the news that grocer Whole Foods Markets (WFM) reached an agreement to be acquired by Amazon.com (AMZN 3.45%) has been perhaps the biggest merger news of the year.

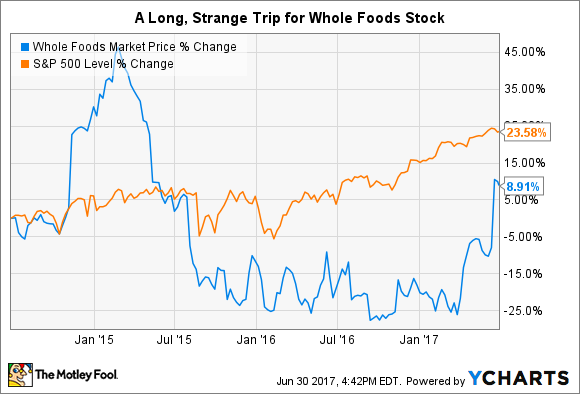

After struggling for some time, Whole Foods shares have since soared to near the $42 acquisition price.

However, the prolonged, multi-year slump in Whole Foods stock that preceded the buyout news is also worth considering, even as investors focus on the potential the merger might unlock.

It pays to consider the contrarian case for any prospective investment. So while I'm bullish on Amazon -- and now Whole Foods by extension -- let's review the potential risk factors and examine the case against Whole Foods as a part of Amazon.

Whole Foods and Amazon: A major minor step

Though the reactions toward the deal were generally positive, they could be overblown. Looking at a number of analyst reports since the news broke on June 16, it becomes clear that the deal isn't a magic bullet for Amazon in regard to its longtime interests in the grocery space.

The deal does give Amazon a toehold in the $647 billion market for U.S. edible groceries. But according to logistics consulting firm MWPVL International Inc., Amazon has only about one-tenth of the grocery-specific warehouse capacity of its chief retail rival, Wal-Mart (WMT 0.06%), and Whole Foods' relatively small footprint of 15 distribution centers does little to change the dynamic.

In fact, one analysis suggested Amazon would need to build at least 12 more distribution centers throughout the U.S. to meaningfully close the gap between itself and Wal-Mart. Moreover, each warehouse constructed for handling perishables is much more complex -- and expensive -- than Amazon's standard distribution centers are, requiring as many as six refrigerated areas. These specialized grocery distribution centers can also require FDA clearance in some cases. The upshot is that Amazon will need to undertake another round of substantial investment to scale out its long-term vision for Whole Foods.

In a similar vein, a research note from Wells Fargo analyst Zachary Fadem noted that Amazon will also need to invest in a fleet of refrigerated delivery trucks to bring grocery delivery to a mass-market scale. Furthermore, Fadem estimates that entering the notoriously low-margin grocery business will do little to help Amazon's profit margin or improve Prime membership growth.

So while buying Whole Foods helps Amazon move toward its goal of becoming the "everything store," it doesn't win the battle for online retail supremacy.

Image source: Amazon.com.

Playing the long game

At the same time, the Whole Foods acquisition is classic Amazon. It demonstrates Amazon's focus on winning over the long term even if it raises questions about the near-term impact.

For example, we already discussed the near-term investments necessary to scale Amazon's grocery efforts to a national level. That concern ties into a host of additional questions about the impact a new wave of major capital expenditures would have on Amazon's cash flow margin and returns on capital over the next several years. From this perspective, Amazon and its shareholders would seem to have been better served by passing on a struggling grocery retailer like Whole Foods.

But those sharing Amazon's long-term perspective would see the unappealing short-term effects as necessary steps toward strengthening Amazon's retail grasp. Like brick-and-mortar retail before it, the mass-market grocery retail business model hasn't undergone a paradigm shift since the rise of the supermarket, but emerging trends such as autonomous delivery drones and self-driving vehicles should help overcome many of the "last mile" pain points that have frustrated would-be innovators for years. By owning Whole Foods' brand, customer data, and infrastructure, Amazon inches one step closer to bringing these changes to fruition.