From 1969 to 1972, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration conducted a series of manned landings on the moon. They "planted the flag," played a little golf, and took some cool home movies. They also collected and brought back with them 842 pounds of assorted moon rocks for examination.

That's a lot of rocks, but now NASA wants more.

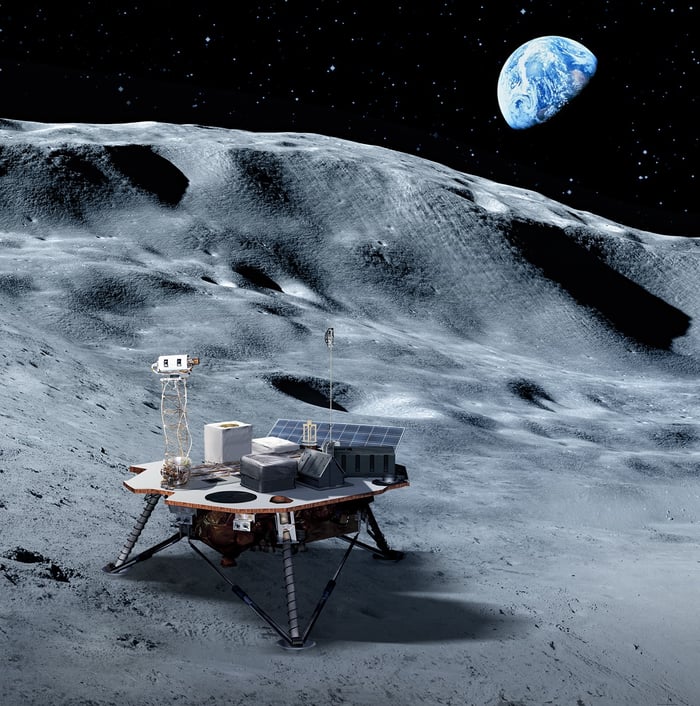

Image source: NASA.

Moon rocks wanted, no shipping required

Last week, America's space agency issued a "request for quotations" (RfQ) for the "Purchase of Lunar Regolith and/or Rock Materials from Contractor," supplemented with an explanatory note from NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine. Together, the two documents describe a novel plan to pay one or more contractors to collect and transfer ownership of moon rocks to NASA -- without ever bringing the payloads back to Earth.

Contractors, says the statement of work, will have complete freedom to determine how they will get to the moon, and how they will collect rock samples once they arrive there. The only fixed conditions are that contractors must collect between 50 grams and 500 grams of moon rocks by 2024, tell NASA where to find the rocks, send photographs of what they have collected, and transfer legal ownership rights to NASA in situ.

To be clear, there is no need for a contractor to bring the rocks back to Earth. NASA will travel to the moon to claim them itself.

As far as payment goes, NASA intends to pay 10% for the moon rocks upon award of the contract, 10% more once a contractor's mission to the moon launches, and the final 80% upon legal transfer of the title to the rock sample to NASA. 10%, 10%, and 80% of what, precisely, has not yet been determined. (NASA is asking contractors to name their best price.) What is curious, though, is this detail: The price "is not dependent on the quantity of Lunar material collected."

Curiouser and curiouser

Did you catch that? NASA doesn't necessarily care how many rocks a contractor collects for it. The agency isn't even requiring contractors to bring rocks back for it to examine. It may "determine retrieval methods for the transferred lunar regolith at a later date" -- or it may not.

NASA could just as easily decide to let sleeping rocks lie, and never collect them at all.

When read as a whole, this almost sounds like NASA doesn't care what contractors end up collecting. It kind of sounds like this entire project was built to encourage contractors to figure out a way to get to the moon and collect just about anything there.

And in fact, I think that is the point.

NASA's not-so-secret plan for solar system domination

What NASA is aiming for is to establish a framework and a market for "in-situ resources utilization." (Indeed, these are the very words Bridenstine uses to describe the project.)

In offering to "purchase ... Lunar Regolith and/or Rock Materials," what the space agency is really doing is trying to remove a bit of the risk factor from companies investing in the space economy, so as to spur growth in the space economy. It is assuring private companies that if they succeed in reaching a space object -- be it the moon, Mars, an asteroid, or anywhere else off-planet -- and they are able to find some sort of valuable resources there and collect them, they will find in NASA a ready buyer for their treasures.

Will NASA succeed in this?

That remains to be seen. It's still early innings in this latest space race, and we won't know which companies respond to NASA's invitation to offer "quotations" until the deadline for submissions arrives on October 9 at the earliest. And even succeeding in their bids, there will be the technical hurdles to overcome. Bidders will have to either be "space companies" capable of launching rockets of their own, or able to partner with companies such as United Launch Alliance, SpaceX, or Rocket Lab to do so. They'll need to possess the engineering know-how to build robots that can move around in a near-weightless environment upon arrival on the moon, and also mining know-how to extract their samples from the lunar surface too.

At the very least, it should be interesting to see who attempts to bid on the work, as this might give us an inkling of which companies have their eyes on future space endeavors such as mining asteroids for precious metal, or mining Mars for water in the years to come. In the nearer term, according to the instructions attached to the RfQ, contractors interested in fetching moon rocks for NASA must keep their bids open for 30 days after the October 9 deadline for submission.

Keep your eyes peeled to for NASA to begin naming winners in November.