Two weeks ago, Earth suffered a disaster in space.

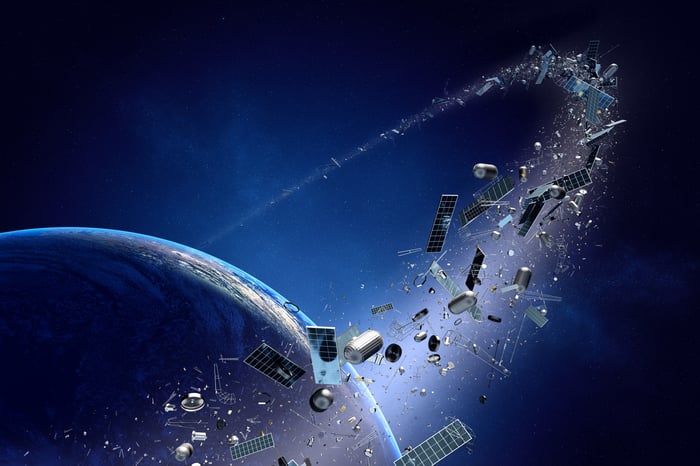

On Monday, Nov. 15, 2021, Russia blew up one of its defunct Kosmos spy satellites with an anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon. The in-orbit explosion transformed one two-ton hunk of dead satellite into a debris field spanning 1,500 pieces of "trackable orbital debris" -- and an untold number of pieces of debris too small to be easily tracked.

This "dangerous and irresponsible" destruction of a satellite, said the U.S. State Department, immediately endangered the lives of astronauts working aboard the International Space Station (ISS), forcing them to shelter in place multiple times as ISS passed through the debris field.

It also illustrates a danger to investors in space companies -- and an opportunity, too.

Image source: Getty Images.

A threat that could persist for decades

"All nations have a responsibility to prevent the purposeful creation of space debris from ASATs and to foster a safe, sustainable space environment," declared NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. And it's not surprising he's upset.

Two weeks after the test, the debris field remains so dangerous to space operations that NASA had to cancel a planned spacewalk outside of ISS this week. A threat assessment from the United States Space Command warns that the debris cloud will pose a continuing threat to space operations for "decades."

The test has already affected operations at private space company SpaceX, which was forced to change the orbits of some Starlink internet satellites to avoid collisions with errant satellite parts. China's space station, too, was apparently put at risk by the test, and in Europe, European Space Agency head Tim Flohrer warned that satellites orbiting "up to the 600-kilometer orbit" will henceforth have to adjust their orbits twice as often as they used to, to avoid the debris.

And the Russian ASAT test highlights one other, even more significant risk.

Big satellites make for fat targets

Consider what happened to space company Maxar Technologies (MAXR) in 2019 when its 2.5-ton WorldView-4 digital imaging satellite suffered a gyroscope failure. In an instant, the $2 billion company lost a $155 million asset, as well as all the future revenue that asset would have generated for the company -- $85 million a year, or about 4% of the company's revenue stream, according to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence.

It didn't take a rocket to kill WorldView-4. A simple parts failure was all that was required to cripple the satellite and to cost Maxar 31.5% of its market capitalization in a single day. But the loss of WorldView-4 illustrates the risk to corporations depending on large, hard-to-replace satellites for their business.

Consider: According to the Federal Aviation Administration, the entire United States GPS system depends on just 31 large GPS satellites built by defense and space juggernauts Boeing and Lockheed Martin. Similar in size to Maxar's WorldView satellites, these GPS satellites would make tempting targets in a time of conflict -- shooting down just a handful of them could cripple GPS capability around the world. For that matter, as providers of surveillance photos to the U.S. military, satellites like WorldView-4 could also be considered legitimate targets of ASAT weapons in a time of military conflict.

Even absent intentional, hostile action, large satellites could be rendered unusable accidentally if struck by space debris from an ASAT "test" such as the one Russia executed last month.

The risk to investors -- and the opportunity

But is there any way to protect critical satellite systems from destruction by ASATs -- or at least discourage the use of ASATs to target them?

In a word: Yes. And I think this is a solution investors in particular should be paying attention to.

The solution: Don't launch a handful of big satellites that can be easily targeted by a few ASATs. Do launch huge numbers of smaller satellites to build in redundancy, so that killing just one (or even a dozen) satellites won't significantly disrupt the constellation as a whole. And build small rockets that can launch quickly to replace any satellites that stop working (for whatever reason), to further harden the system. By eliminating the ability of ASATs to disrupt satellite operations, you dissuade countries like Russia from launching, or even testing ASATs -- minimizing the risk that such tests will leave behind debris fields in orbit like the one Russia just created.

I'm not the only one to stumble upon this idea, of course. Indeed, you can see the kernels of this idea in the "Launch Challenge" that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA -- the Pentagon's mad scientists division) announced in 2019 to promote "on-demand, flexible, and responsive launch of small payloads" for defense. You could also argue that part of the reason SpaceX has wanted to put thousands of small Starlink satellites into orbit, instead of just a few big broadband satellites, is to build redundancy into its system, so that the loss of a few satellites won't cripple the whole system.

The more this way of thinking gains traction at the Pentagon, the more I think you'll find that investments in companies like York Space Systems (which builds small satellites) and Rocket Lab (which launches them) will outperform companies like Boeing and Lockheed, which continue to focus on building and launching satellites so big that you can see them in orbit -- all the way from Russia.