Northrop Grumman (NOC -1.27%) could be as little as 18 months away from becoming a top space stock, on par with the likes of Arianespace, United Launch Alliance, or SpaceX.

Of course, Northrop already is a space company. When it bought Orbital ATK back in 2018, Orbital's families of Pegasus, Antares, and Minotaur rockets came along as part of the deal. Now in possession of Orbital (since rebranded as Northrop's "Innovation Systems" division), Northrop is responsible for making periodic supply runs to the International Space Station (ISS) using its Antares medium-lift rockets. But Antares' 8-ton payload isn't big enough to really compete with the giant Atlas V rockets operated by ULA or with SpaceX's Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy.

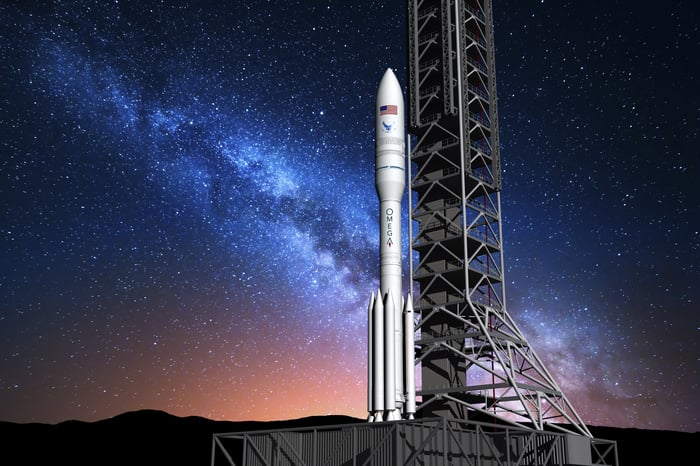

To do that, Northrop needs a new rocket. A bigger rocket. An OmegA rocket.

Image source: Northrop Grumman.

Whereas Antares can carry 8 tons of payload to a low Earth orbit suitable for supplying ISS, Northrop's new OmegA rocket, in its "heavy" configuration, will be able to carry nearly as much cargo to a much higher geostationary equatorial orbit, allowing it to compete with the likes of ULA and SpaceX for missions Antares could never fulfill. Of course, before OmegA can do that, Northrop needs to get its new rocket certified to perform these missions, safely, by the United States Air Force.

Last week, Northrop announced its first step toward doing just that.

Certification is step one

On Thursday, Dec. 12, Northrop announced that privately held, Colorado-based Saturn Satellite Networks has signed on to become its inaugural customer.

Sometime in the spring of 2021, OmegA's first launch will carry "up to two" of Saturn's NationSat small GEO satellites into orbit on its first-ever launch. Northrop didn't reveal what it's charging Saturn for this service -- but honestly, the price is almost beside the point of this mission.

More important is the fact that the launch will be the first step toward getting OmegA certified to perform "national security" missions for the U.S. government, such that Northrop will stand a chance of winning one of two multibillion-dollar Launch Service Procurement contracts that the Air Force will be awarding next year. With LSP-2 ordering launch missions for the 2022 to 2027 time frame, it's crucial that Northrop get its newest rocket certified as fast as humanly possible.

Will a 2021 launch be soon enough to accomplish this? Perhaps. Luckily for Northrop, the Air Force has recently become more lenient in its certification policy. Last year, the service certified SpaceX's Falcon Heavy to perform national security missions after just one launch. (To put that decision into context, SpaceX's Falcon 9 had to fly 18 missions before it won certification.) If this new risk-tolerant policy holds true for Northrop, it's possible that OmegA could win certification as early as next year.

OmegA's plan B

But what if it doesn't? Or what if despite winning certification, Northrop still doesn't win one of only two LSP-2 contracts up for bid next year?

Well, in that case, Northrop could be in something of a pickle.

Earlier this year, Northrop rival Blue Origin (which is also bidding on LSP) filed a pre-award protest with the Government Accountability Office, arguing, among other things, that while two of the four companies bidding on the contracts will certainly benefit from winning it, anyone who does not win an LSP contract would probably be shut out of government contracts for a term of five years or more. Starved of funds, such a company (be it named Blue Origin or Northrop) would have to find alternate markets for its rocket ship -- or go broke.

And this, in a nutshell, is why I think Northrop Grumman is making such a very smart move in choosing to fly a commercial payload on its first OmegA mission. In its inaugural launch, Northrop is laying down a marker and indicating its determination to seek commercial customers for its new rocket. In so doing, it stands in marked contrast to ULA, which, despite valiant efforts to attract commercial customers, has struggled to crack the commercial market and relies primarily on government contracts to this day. Northrop is also incidentally reassuring its investors that it plans to stick around in this space business for the long term -- with or without government contracts.

And perhaps best of all, Northrop is thinking long term, planning ahead, and preparing to survive in the event LSP-2 doesn't work out for it. I think that's a savvy strategy, and Northrop Grumman management should be commended for it.