A Roth conversion involves moving funds that are held in either a traditional IRA or a standard 401(k) into a Roth IRA. The benefit of doing a Roth conversion is twofold: a lower tax burden in retirement and no required minimum distributions (RMDs).

This conversion process is not as simple as it sounds. Before you count on the prospect of lower taxes and more freedom to hold money in your account, look at these six must-know facts about Roth conversions.

1. You must pay taxes on the converted amount in the year of the conversion

The contributions you make to a traditional 401(k) from your paycheck are pre-tax, as are most traditional IRA contributions. In return for that current tax deduction, you agree to pay income taxes on distributions from those accounts later on.

The Roth IRA takes a different approach. Your Roth contributions are made with after-tax funds, but then your distributions are tax-free.

In other words, a traditional IRA gives you a tax break now. A Roth IRA gives you a tax break later.

When you move 401(k) or traditional IRA funds into a Roth account, you're taking pretax contributions and putting them into an account that's designed for after-tax contributions. For that reason, you have to pay income taxes on the converted amount.

Say you decide to convert $10,000 of pre-tax contributions from your traditional IRA to a Roth IRA. The $10,000 will be added to your gross income for the tax year. If your marginal tax rate is 22%, you'd owe up to $2,200 on the conversion. But it could be more than that if the extra income pushes you into a higher tax bracket.

Plus, if you're younger than 59 1/2, you can't use any of the converted funds to pay these taxes since the IRS would consider that an early distribution. As a result, you'd be hit with a 10% penalty on top of income taxes, so you should plan on paying the taxes out of your cash savings.

If you're older than 59 1/2, you could pay the taxes out of the converted funds without incurring a penalty. But doing so would lower your invested balance and your future income potential, which isn't ideal.

Alternatively, you may want to pay these taxes out of pocket by making a quarterly tax payment. This allows you to reinvest the entire converted amount in your Roth IRA.

2. Roth conversions aren't right for everyone

Think of a Roth conversion as a strategy to prepay your retirement income taxes. You'd do this only if you think your tax rate today is lower than it will be in retirement.

You might be in the 12% tax bracket right now, for example. But thanks to disciplined saving, you expect to be in the 22% tax bracket once you retire. Or, you might feel strongly that tax rates generally will rise in the future, maybe pushing the 12% tax bracket to 15%. In either case, the conversion would enable you to pay a lower tax rate now, rather than a higher tax rate later.

On the other hand, if you expect your tax rate to be lower in retirement for any reason, a Roth conversion isn't the right move. You don't want to pay more today when you could pay less in the future.

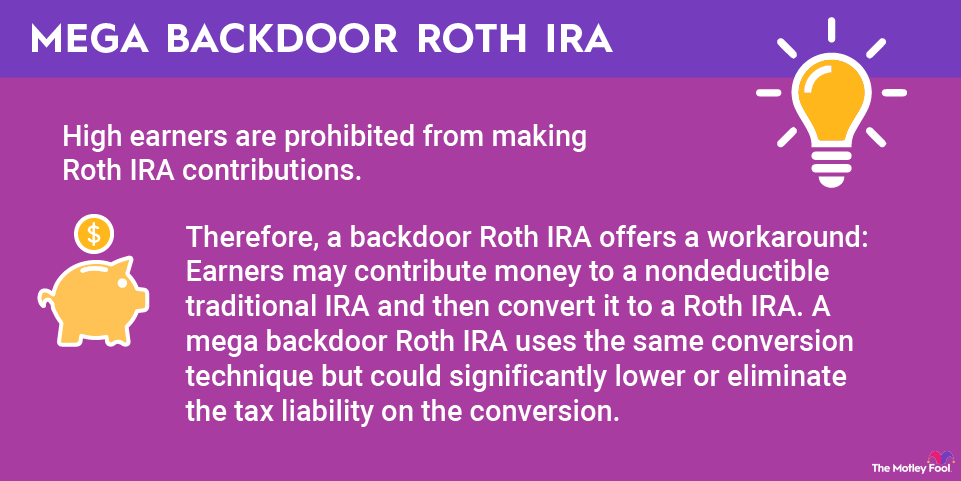

3. You can still do a Roth conversion even if you're over the Roth IRA income limits

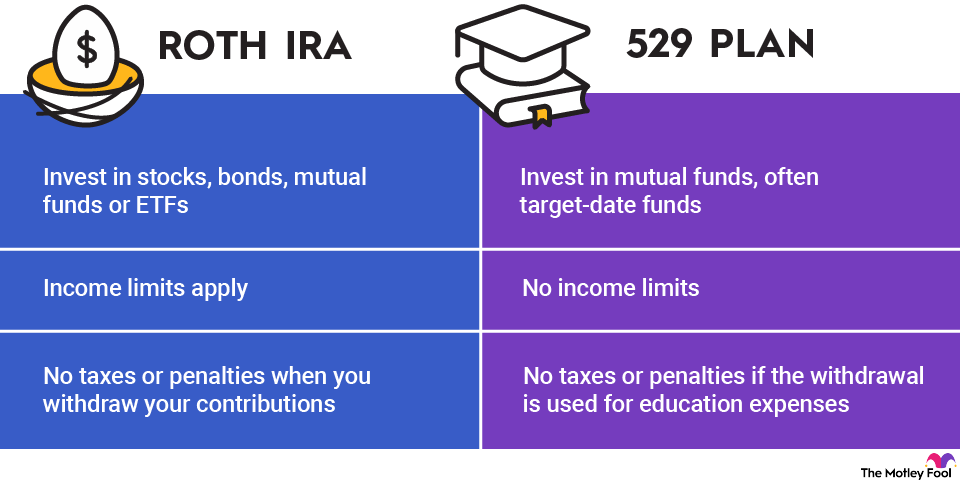

Each year, the IRS sets income limits on Roth IRA contributions. These limits may lower the amount you're allowed to contribute or prohibit you from making any Roth IRA contributions at all.

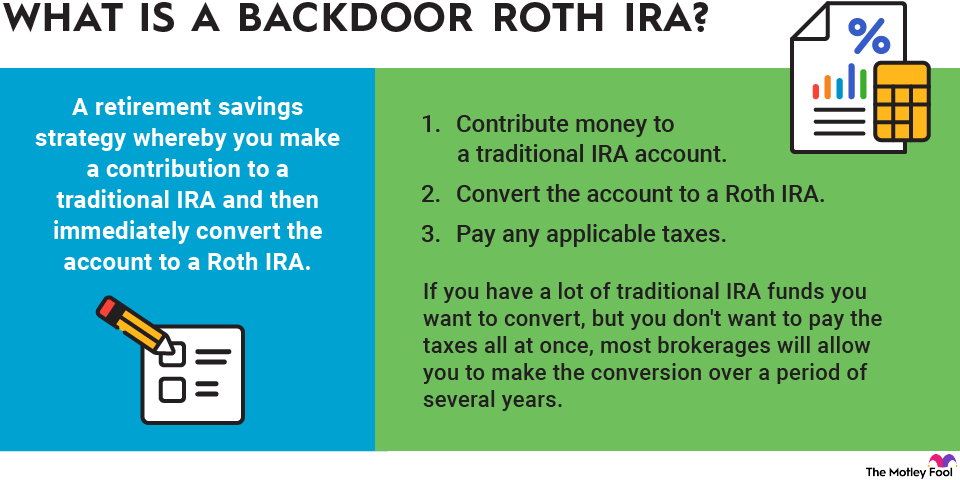

Interestingly, Roth IRA income limits don't apply to Roth conversions. So, even if you make too much to contribute directly to a Roth IRA, you could still contribute to a traditional IRA and then do a conversion. This is what's known as a backdoor Roth IRA. The end result is the same as a direct contribution, but you have to jump through a few more hoops to get there.

4. Conversions of nondeductible IRA contributions may be taxable, too

Don't assume you can make a nondeductible IRA contribution and then immediately convert it to a Roth IRA without tax implications. This only works if you have no other IRA balances funded with pre-tax contributions. Otherwise, the IRS assumes a portion of your conversion is taxable based on the composition of your nondeductible and deductible IRA balances. You don't have the option to convert only your nondeductible contributions, even if they're held in a separate account.

That all sounds messy and complicated -- because it is. Know that if you want to convert nondeductible contributions and you have other IRA assets, it's smart to consult with a tax advisor before making any decisions.

5. You can't reverse your decision

Prior to 2018, you could "recharacterize" your converted Roth funds back to pretax contributions. That was the action you'd have to take to undo your Roth conversion. Today, recharacterization of converted Roth funds is prohibited by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. In other words, there's no going back once the conversion is done.

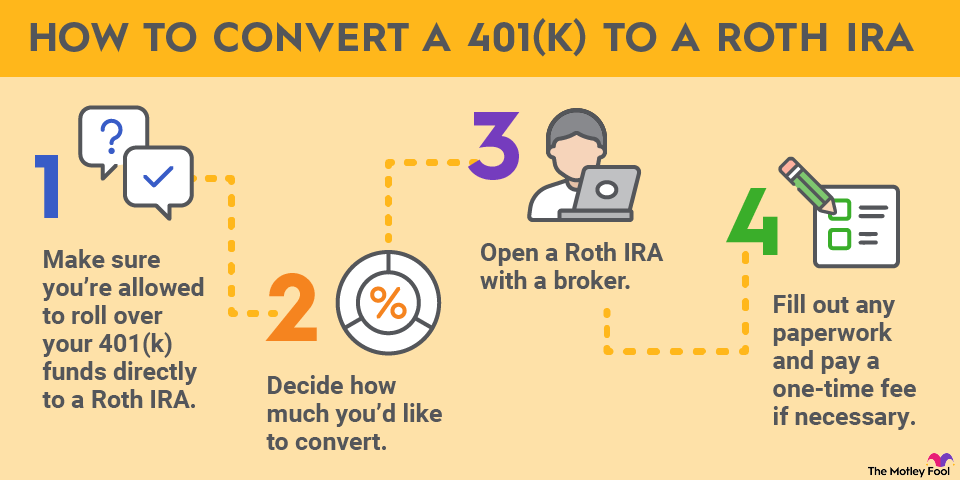

6. Roth conversions are available for 401(k)s, too

Roth conversions aren't just for your traditional IRA balances. If you've left a job and still have funds in your former employer's 401(k), you can convert some or all of that money to a Roth IRA. This is an alternative to the conventional, nontaxable 401(k) rollover that would move your savings into a traditional IRA.

A 401(k) Roth conversion is taxed in the same way as an IRA conversion. You'd owe income taxes on pretax contributions plus any earnings.

As with an IRA, if you have any nondeductible contributions in your 401(k), the taxation gets more complicated. Generally, you'll incur taxes for converting the pro-rata share of pretax funds in your account. If you don't have nondeductible contributions, things are more clear-cut. You'd simply pay taxes on the entire converted amount.

Is a Roth conversion right for you?

A Roth conversion lowers your tax bill in retirement, but it's not the right move for everyone. Before you move forward, it's important to carefully weigh the costs today against the expected benefits in the future.

Your costs today will be the tax on your converted funds, which you'd ideally pay from your cash savings. The future benefits you receive from a Roth conversion are tax-free withdrawals and the elimination of required minimum distributions.

To quantify the value of tax-free withdrawals in the future: Estimate your tax rate in retirement relative to your tax rate today. On paper, the conversion makes sense when your expected tax rate in retirement is higher than your tax rate today.

To quantify the elimination of RMDs: Forecast the longevity of your retirement funds. If you expect to use almost all of your savings on living expenses in retirement, RMDs may be irrelevant since you'll be withdrawing the funds anyway.

Conversely, you might expect to have a surplus of funds that you could leave behind as an inheritance. In that case, avoiding RMDs lets you keep your money invested and growing tax-free, which should create a larger legacy for your loved ones.

Take your time on this cost/benefit analysis. Move forward only if you feel reasonably confident that you have the cash on hand to pay the taxes and that your tax rate in retirement will be higher than it is today.