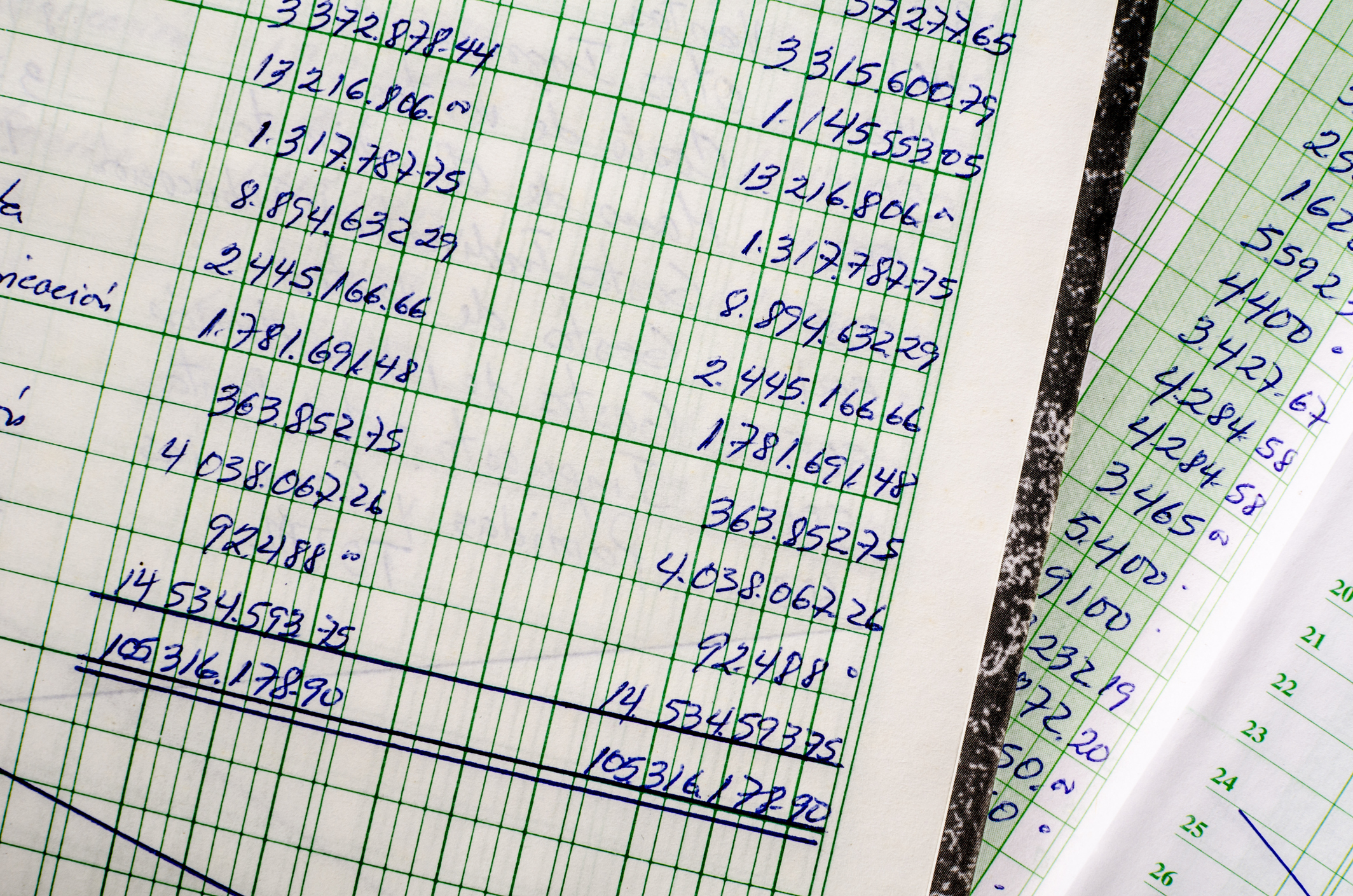

Mark to market (MTM) is an accounting method whereby assets and liabilities are recorded at their current market value. In other words, if a company had to liquidate its assets and pay off all its debts today, mark to market accounting would give you an accurate picture of how much it would be worth. It’s also used in valuing accounts holding financial instruments like futures and mutual funds.

How mark to market works

Mark to market will adjust the value of assets held on a balance sheet or in an account based on the current market value of those assets. Mark to market differs from historical cost accounting, which simply records the value of the asset as the amount paid. That value doesn’t change until the company decides to write down the value or liquidate the asset.

For example, let’s say a company decides to invest its cash in long-term Treasury bonds. If interest rates rise following that investment decision, the value of those bonds will decline. If those assets are marked to market each quarter, the company will show a value that’s less than what it originally invested. If interest rates fall, the value will go up, and the company can show an increase in asset value.

That’s regardless of whether or not the company intends to hold those Treasury bonds until maturity, at which point they could be redeemed for the full face value. But using mark to market accounting can give investors a full picture of how market conditions have affected a company’s investments.

Mark to market accounting gives shareholders and potential business partners a better understanding of a company’s current balance sheet.

If a lender makes a loan, it ought to account for the possibility that the borrower will default. If it can’t collect on the loan, the loan has no value. Therefore, a contra asset marked as an allowance for bad debt can ensure the balance sheet is marked to market.

Wholesalers use mark to market accounting when they need to adjust the value of their accounts receivable asset. Many wholesalers will offer discounts to purchasers if they pay sooner. Depending on the percentage of customers likely to accept a discount for shorter payment terms, a wholesaler will need to mark down its accounts receivable to the market value using a contra asset account.

Mark to market accounting in investment accounts

Market to market accounting shows up in investment accounts in two ways.

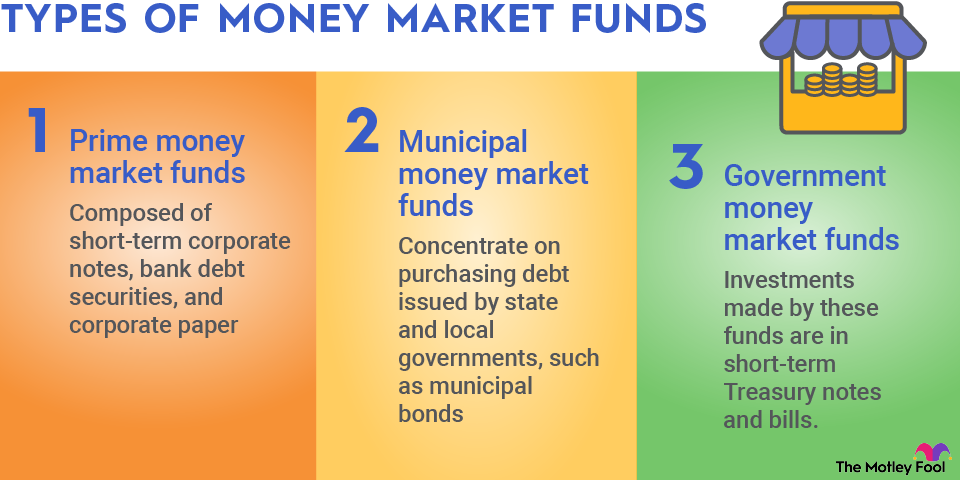

The first way affects many retail investors. If you invest in a mutual fund, the assets held by that mutual fund are marked to market at the end of every trading day. This is known as the mutual fund’s net asset value, and it’s the price you’ll pay for shares or receive when redeeming shares. Note that mutual funds’ prices do not fluctuate during the trading day, and purchases and redemptions happen only at the end of the day after the funds assets are marked to market.

The second occurrence is in futures trading. When you open a futures position, you’re not actually buying anything. You’re simply entering into an agreement to buy or sell a commodity at some point in the future. In order to ensure you can settle that contract, your broker will require you to hold a certain amount of cash, typically a relatively small percentage of the contract’s value.

At the end of every day, the broker will mark to market the value of the futures contract. If the total value of the contract increased, it’ll add cash to your account. If it decreased, it’ll deduct cash from your balance. If the value of the futures contract declines too much, you may fall below the margin requirements set by your broker, which will force you to liquidate your position or add cash to your account.

Related investing topics

Examples of drawbacks in mark to market accounting

While mark to market accounting may give a better snapshot of what the assets on a company’s balance sheet would be worth if it had to liquidate them today, that can have some negative consequences.

Mark to market accounting can accelerate a recession. As an economy is crashing, businesses will have to mark down their assets and investments, leading to a snowball effect and additional bankruptcies.

Bankruptcy

In boom times, mark to market accounting could artificially inflate balance sheets. That could lead businesses to take on more risk than they should, given the backstop of their inflated assets. But a drop in asset values could expose that risk. We saw that play out in 2008 as mortgage-backed securities increased in value, leading to looser lending decisions from banks.

A bank intending to hold a Treasury bond or other debt with extremely low default risk until maturity may not mark to market the value of that security. If the market price is lower than face value, it may indicate the bank doesn’t have enough assets to cover its deposits. But if it simply holds those securities to maturity, it’ll be able to pay out all depositors.

The information provided by mark to market accounting can be very valuable to investors and other stakeholders, but it should be taken within the context of the overall market and the company’s plans for those assets.