It's been a few weeks since U.S. forces captured former Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro, with that geopolitical event stirring optimism in the commodities complex that the country with the world's largest petroleum reserves will finally be open to Western oil majors.

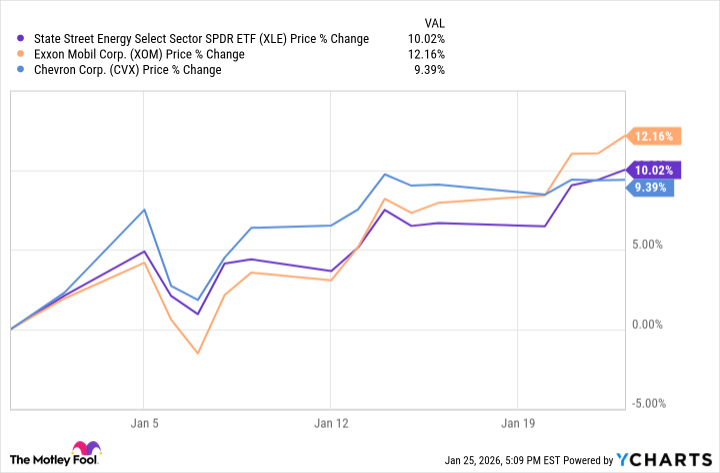

That enthusiasm is proving palpable. Just look at the State Street Energy Select Sector SPDR ETF (XLE +1.36%). One of the bellwether exchange-traded funds (ETFs) dedicated to energy stocks, that fund is up 10% year to date. ExxonMobil (XOM +1.80%), a stock that accounts for 24% of that ETF's roster, has done even better, gaining 12.2% since the start of 2026.

ExxonMobil may not be the exciting Venezuela play some investors are hoping for. Image source: Getty Images.

Logically, some investors are apt to attribute some of that bullishness to events in Venezuela. Still, market participants need to be careful when betting on Exxon as a beneficiary of regime change in the South American country. Let's get into why that's the case.

An ExxonMobil/Venezuela bet may not pay dividends

Answering the question, "Can Venezuela boost ExxonMobil's long-term cash flows?" is easy. The clear answer is, "yes," and it would potentially be a good thing, too, because when the company reports full-year 2025 results, it's likely to mark the third consecutive year in which free cash flow (FCF) declined.

However, investors cannot afford to leave it at that. Currently, Chevron (CVX +1.43%) is the only Western integrated oil major with existing operations in Venezuela. ExxonMobil hasn't pumped petroleum there since 2007, when its assets were seized by then-president Hugo Chavez, marking the second time the company endured such a situation in that country.

To the credit of Exxon management, they're not chastened by that ominous history. At the White House earlier this month, CEO Darren Woods overtly said there's opportunity in Venezuela, which is a member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

But investors shouldn't interpret those remarks as an opportunity set to come to fruition imminently. Even if the company signed Venezuelan leases today, which isn't going to happen, it could be at least several years before it's consistently pumping oil in the Orinoco Belt.

ExxonMobil investors may want the company to avoid Venezuela

To reiterate, if ExxonMobil enters Venezuela, it could be supportive of long-term cash flow, with "long-term" being the operative phrase. It could be years before Venezuela exposure delivers benefits to this company's shareholders.

In fact, those investors may be just fine if ExxonMobil avoids Venezuela altogether because the country's value proposition for oil producers isn't as attractive as some market participants might assume, and that's true even when accounting for the possibility of a new, U.S.-friendly regime taking power there.

Simple math confirms why Venezuela may actually be more risk than reward for ExxonMobil. The company can break even at around $35 per barrel at its Guyana project and $48 per barrel in Texas's Midland Permian Basin. However, that latter figure may decline due to some new technology. In Venezuela, the estimated break-even price for any producer is $42 to $56 per barrel, and in the Orinoco Belt, it's north of $49.

Said another way, the math is better in lower-risk locales, and that's not lost on ExxonMobil. It shouldn't be lost on investors, either.