Congratulations, American workers: You're more profitable than ever!

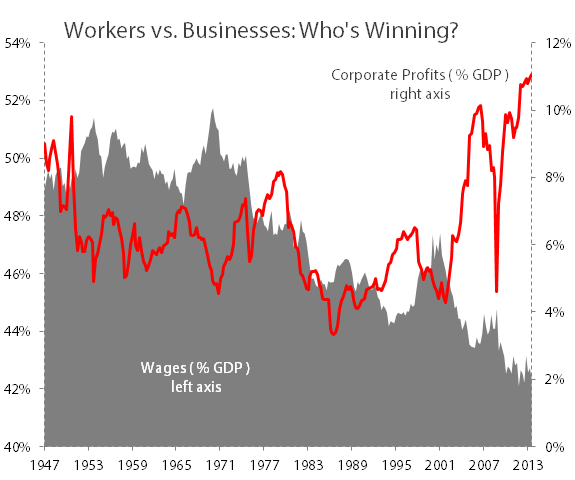

I doubt too many of you are applauding, and there's little reason why you should. After all, the flip side to record-high corporate profits is that the wages paid to American workers are lower than they've ever been:

Source: St. Louis Fed; corporate profits after taxes, without adjustments.

But wait! Aren't the insidious forces of globalization responsible for this huge surge in profitability? After all, as Bloomberg reported last week, America's largest multinationals now hold $1.95 trillion in foreign accounts, which if repatriated tax-free would be enough to send every man, woman, and child in the United States on a $6,200 shopping spree. Eight of the 10 companies with the largest offshore holdings are Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI 1.18%) components -- 13 of the Dow's 30 components held a third of the $1.95 trillion total, with $668 billion between them. Last year's foreign haul of $206 billion could have patched up almost a third of the U.S. budget deficit. Small wonder that a growing chorus of commentators is pitching another corporate cash repatriation holiday.

Let's take a look at how much money those Dow companies have, and how much they could conceivably pay out in one-time dividends per share if their foreign profits were repatriated at a 5% tax rate:

|

Dow Component |

Profits Held Abroad |

Maximum Potential Special Dividend per Share* |

|---|---|---|

|

General Electric (GE 1.54%) |

$110 billion |

$10.41 ... 41.2% yield |

|

Microsoft (MSFT 0.53%) |

$76.4 billion |

$8.84 ... 22.3% yield |

|

Pfizer |

$69 billion |

$10.27 ... 32.4% yield |

|

Merck |

$57.1 billion |

$18.58 ... 33.2% yield |

|

IBM (IBM 2.79%) |

$52.3 billion |

$47.77 ... 25.9% yield |

|

Johnson & Johnson |

$50.9 billion |

$17.09 ... 18.3% yield |

|

Cisco (CSCO 0.31%) |

$48 billion |

$8.85 ... 40.9% yield |

|

ExxonMobil |

$47 billion |

$10.34 ... 11% yield |

|

Procter & Gamble |

$42 billion |

$14.72 ... 18.7% yield |

|

Chevron |

$31.3 billion |

$15.57 ... 13.5% yield |

|

Coca-Cola |

$30.6 billion |

$6.59 ... 17.3% yield |

|

JPMorgan Chase |

$28.5 billion |

$7.20 ... 12.4% yield |

|

United Technologies |

$25 billion |

$25.95 ... 22.8% yield |

Monstrous, isn't it? If you stop counting all of this foreign cash, American businesses might not seem so historically powerful -- after all, what's the point of tallying up profits if corporations can't actually use them in this country? Narrowing our focus to look only at domestic profits should show us a more modest level of corporate profitability.

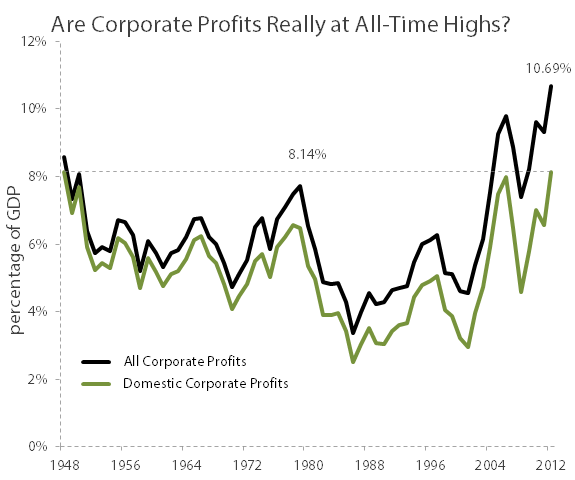

But this conventional wisdom is wrong, at least to a rather large extent. Overall corporate profits are at all-time highs as a percentage of U.S. GDP; even when you strip out the foreign component of corporate profit, businesses still earned about as much profit as a percentage of GDP in 2012 as they did during their old glory days during the early postwar years:

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis and St. Louis Fed; after-tax profits.

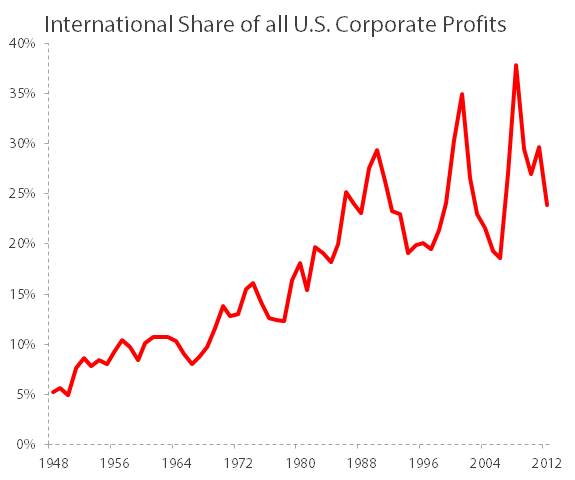

Keep in mind that after-tax corporate profits continued to increase in 2013, and when we examine the international component of U.S. corporate profits, it's easy to expect that the next annual update will show a new all-time domestic profit high:

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis and St. Louis Fed; after-tax profits.

International profits make up a larger slice of the overall profit pie during recessions -- successively higher peaks in 1974, 1990, 2001, and 2008 all correspond to recessions and market lows. Conversely, economic strength has brought the international component of corporate profits down to about 20% of all profits twice since the start of the "dot-com era" of modern automation (a subject I briefly covered yesterday). Absent the onset of an unexpected recession, it seems likely that we'll see international profits hit that level again.

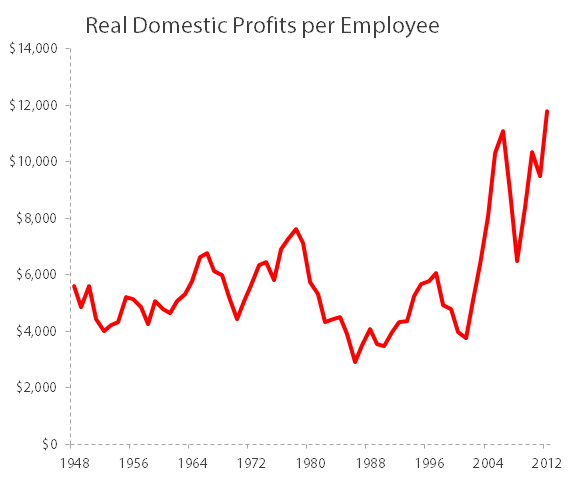

Globalization has affected U.S. businesses, but it's not the only reason why wages are down and profits are up. In fact, even when you remove international profits, the typical American worker is still about 200% more profitable to his or her typical American company today than he or she would have been at the turn of the century:

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis and St. Louis Fed; corporate profits after taxes, adjusted for inflation with CPI.

This is what really matters, and it's also an easy (though hardly comprehensive) way to explain the divergence between profits and wages. The number of private-sector employees has barely changed since the turn of the century because businesses don't need more employees to make more money. Despite the appearance of a long-term decline on the first chart, the wage share of GDP dropped by only 5% from 1951 to 2001, but it fell by 11% from 2001 to 2013. Wage earners have already lost more economic power in the 21st century than they did in the latter half of the 20th.

It looks like workers are more valuable, but what all of this really means is that each worker is a lot more productive with the tools at his or her disposal. Much of that is because the workers at the top -- the programmers at Microsoft and IBM, the network engineers at Cisco, the drug researchers at Pfizer and Merck -- can produce something that can be sold around the world in less time and with less of a support infrastructure than similar enterprises might have needed in the 1950s. The waiters and checkout clerks at the bottom of the workforce ladder are probably barely more efficient today than their predecessors, as the Bureau of Labor Statistics recorded a 15% improvement in productivity per hour and a barely there 4% improvement in productivity per person for bars and restaurants since 1987. In contrast, software publishers have experienced gains in productivity per person and per hour worked of about 1,800%! Services such as travel booking and job search that leverage the Internet for growth have experienced impressive productivity growth in even less time, as their tracking periods only begin in 1998, when the Internet began to take off.

American businesses are hugely profitable in the rest of the world, but they continue to make the lion's share of their money right here at home, using about 5% more private-sector workers than they employed at the turn of the century to make roughly three times as much on the bottom line. The major driver of corporate profits isn't globalization, it's automation-driven efficiencies -- and there's no reason why this trend must necessarily revert to any long-run "historical" average. After all, as I've mentioned earlier, businesses only need to hire when they're swamped with demand, and technology has made it easier than ever to manage business demand without bringing on new workers.