Source: US Geological Survey.

By now, you've probably heard of all the benefits that the U.S. shale boom has brought: We're importing less oil, production is supporting job growth, industries are coming back to the U.S. because of the energy savings, etc. I'm guessing you haven't heard this one, though:

Were it not for what's happened these last few years -- we'd be looking at an oil crisis. We'd have panic in the public. We'd have angry motorists. We'd have inflamed congressional hearings and we'd have the U.S. economy falling back into a recession. If it were not for the U.S. oil boom, we would be in a world oil panic and spiraling into another global recession.

Those aren't my words -- they are from Daniel Yergin, author of The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World, at the U.S. Energy Information Administration's annual conference. As bold as his statement may sound, there's a lot of evidence to back it up. Let's take a look at what has happened in the world oil markets during the past several years to fully understand and appreciate what oil production in the U.S. has done for the world.

The new "peak oil" theory

The theory of peak oil production is not a new one; it just comes and goes with time. The first scare was in the 1880s, when production in Pennsylvania, then the largest oil producing part of the world, was on the decline. So far, every time we've feared that geology would win, we have found more oil and gas, thanks to new technology and higher prices that make that oil accessible. In fact, if oil prices were considerably higher than they are today, then another trillion of barrels of other oil sources could open up right here in the U.S.

Instead of thinking of peak oil as a geology problem, perhaps it's an economic and political problem. As Total CEO Christophe de Margerie put it, the best way to think of our oil market right now is peak production capacity, because of the political constraints that have kept global oil production from reaching its potential. What does he mean by this? Let's simply look at what has happened since 2008, when oil was approaching $150 per barrel.

- War between Sudan and South Sudan has led to oil production being half what it was since then from the now separate countries.

- The Arab Spring has sent Libya into political turmoil, and production there has been cut by almost 1 million barrels per day.

- General malaise, and lack of investment at national oil companies in Mexico and Venezuela, have resulted in production of 900,000 barrels per day less from these two nations combined.

These events, and many others, have resulted in major losses in oil and gas production around the world. In fact, if we were to exclude production from the United States since 2008, global production has only seen a net gain of 500,000 barrels per day. To make matters worse, we are staring at a situation in Iraq that, so far, has not resulted in major oil production losses, but has the potential to disrupt the worlds eighth-largest producer and sixth-largest exporter.

Since 2008 -- and today -- demand for oil hasn't exactly slowed. Growth from Asia, South America, and Africa has increased consumption of oil by 5.1 million barrels per day. Even if OPEC nations were to open all of its spare capacity to meet this surge in demand, it could only potentially make up 1.5 million-2 million barrels per day more than what it's producing today. This inability for the world to meet growing oil demand would likely have seen prices continue to climb after the global financial crisis. It's not too much of a stretch so see the world remaining in the 2008 economic recession if oil prices were that prohibitively expensive.

The one place bucking the trend

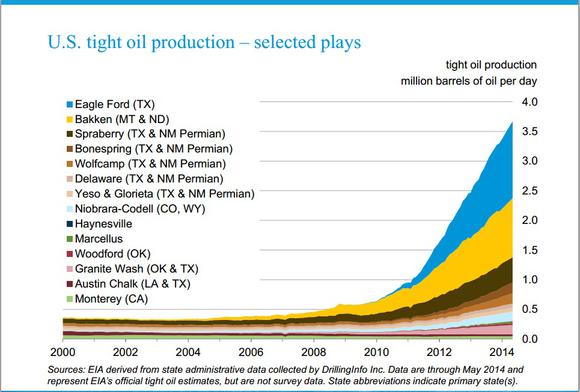

Fortunately, this situation never came to pass because, along the way, oil and gas producers discovered how to economically tap tight oil formations across the U.S. Today, production of tight oil from mostly the Eagle Ford, Bakken, and Permain Basin shale formations have added a significant amount of production in the U.S.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Admininstration.

This boost from shale has not only offset the declines from other production methods, but has been the driving force behind overall production, as well.

Source: U.S. Energy Administration.

From April 2008 until the EIA's most recent data, U.S. net production has surged by 3.2 million barrels per day, the fastest increase in crude production ever in that amount of time. Also not to be discounted is the 1.1 million barrels per day reduction in oil consumption since that time, thanks, in part, to reduced overall driving, and in large part to increased vehicle efficiency. Combined, that's 4.3 million barrels of oil available to the global market, covering 82% of the world's increase in oil demand during that time frame. By covering our own needs for oil during this time frame, it has opened up those supplies to be shipped to other parts of the world, and kept prices relatively stable and in the $100-$110 per barrel range for almost three years, despite all of those aforementioned problems elsewhere.

What a Fool believes

Even though we are three years into the shale boom, we're still realizing the impact it's having here and abroad. According to the EIA, its most recent projection is that production will start to flatten again in 2015-2016, then start to decline by 2020. However, for the last three years, production has blown by the EIA reference case projections, and has more closely tracked its high resource case. If this trend were to continue, then we could see production increase in the U,S, well into the next decade, and grow production at least another 4 million barrels per day. If the amount of oil we have brought on in these past few years has saved us from a global crisis, imagine what future production will be able to do.