So often we think there's no difference between stock trading and investing. But Warren Buffett wants us to think again.

The important insight

When discussing the changes to the Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK-A) (NYSE: BRK-B) investment portfolio in his 1996 letter to shareholders, Buffett began by noting, "Our portfolio shows little change: We continue to make more money when snoring than when active."

This continued a trend from the previous year, when Buffett remarked, "We continue in our Rip Van Winkle mode: Five of our six top positions at yearend 1994 were left untouched during 1995."

Image source: Getty Images.

And from a cost basis, the three largest positions Berkshire held at the end of 1996 -- American Express, Coca-Cola, and Gillette -- were unchanged from the year prior, meaning not a single share was either bought or sold.

You may be asking yourself, how Buffett could even think of doing such a thing? After all, when it comes to buying and selling stocks, isn't beating Wall Street at its own game done by trading on the news of the day?

And the short answer is simply: no.

Buffett goes on to say:

Inactivity strikes us as intelligent behavior. Neither we nor most business managers would dream of feverishly trading highly profitable subsidiaries because a small move in the Federal Reserve's discount rate was predicted or because some Wall Street pundit had reversed his views on the market. Why, then, should we behave differently with our minority positions in wonderful businesses?

As previously mentioned, Buffett encourages investors to always understand when they buy a stock, they aren't simply buying a number, instead they're buying a part -- however small or large -- of a tangible business and the future earnings it generates.

And when we view investments in stocks as tangible businesses we have an ownership stake in, exponentially more often than not, one headline or tough few months shouldn't change our opinion on the business itself.

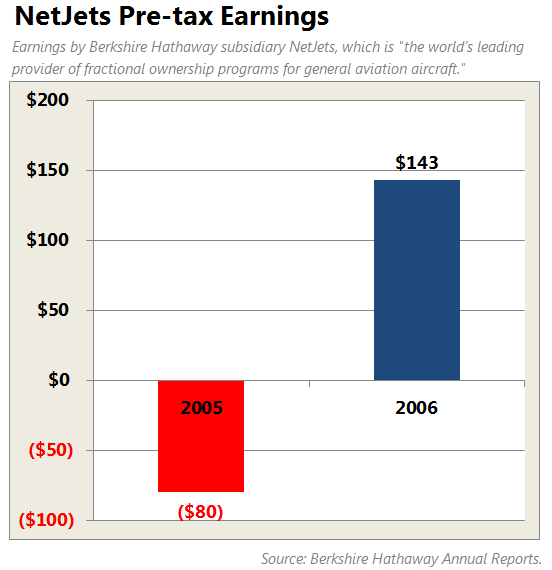

For example, Berkshire's own NetJets subsidiary incurred $80 million in losses during 2005 as demand for its services outpaced supply. As a result, it had to contract out its flights at higher costs (which it didn't pass on to customers). If it were its own company, news like that would likely send the stock price plummeting.

But did Buffett sell NetJets as a result of one bad year? Of course not.

Its fundamental business dynamics hadn't changed, and if anything, increased demand -- which led to the losses -- is a good thing.

So, what happened?

As shown in the chart to the right, thanks to the efforts of an outstanding management team, NetJets righted its ship (or in this case, its planes), and it delivered a profit of $143 million in 2006, a $220 million swing in the right direction.

Put simply, selling NetJets -- which was a wonderful business -- just because of one bad year would've been a disastrous mistake for Buffett.

How to make intelligent investments

So, with all that in mind, how does Buffett suggest we as individual investors actually figure out which businesses to invest in and whether or not we should sell them after the purchase? He goes on to say:

The art of investing in public companies successfully is little different from the art of successfully acquiring subsidiaries. In each case you simply want to acquire, at a sensible price, a business with excellent economics and able, honest management. Thereafter, you need only monitor whether these qualities are being preserved.

This is advice Buffett lives by himself. Remember, he didn't buy or sell any of Berkshire's stake in American Express or Coca-Cola in 1996. And he actually hasn't done so in the nearly two decades since then. Why? Because the fundamental core businesses and their capabilities to generate massive earnings haven't changed for these two titans of American industry.

So, what has this meant for how much those investments are worth? As you can see below, despite not buying or selling a single share, Berkshire's stake in AmEx and Coca-Cola has grown by more than $17 billion in value:

This means Berkshire has been able to turn $2.7 billion into $30.4 billion -- to say nothing of the billions received in the form of dividends over the last two decades -- through long-term investments in wonderful businesses.

The key takeaway

In a 2011 study of behavioral patterns and resulting investment performance of more than 65,000 investors from 1991-1996, Dr. Brad Barber and Dr. Terrance Odean found the 20% least active traders outperformed the 20% most active traders by an astounding 7 percentage points a year.

In other words, $1,000 invested in 1991 might've been worth $2,750 in 1996 for the "buy-and-hold investors" versus $1,900 for those investors who trade most actively, a difference of roughly 50%.

Buffett once said, "The stock market is designed to transfer money from the active to the patient."

Ultimately, we must see that stock traders are those who think they'll make money, whereas buy-and-hold stock investors may often be those who actually make the money.