Monster Beverage (NASDAQ: MNST) was the best-performing stock from 1995 to 2015. It increased 105,000%, turning $10,000 into more than $10 million.

But this isn't a retrospective about how you should wish you owned Monster stock. It's almost the opposite.

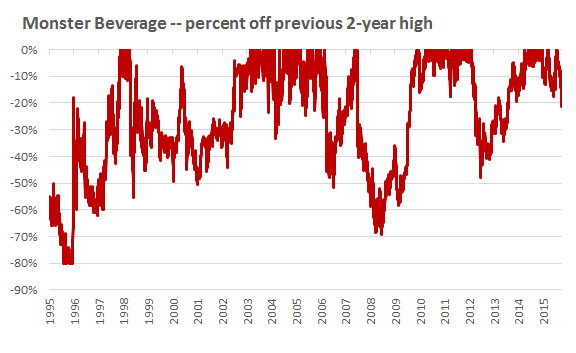

The truth is that Monster has been a gut-wrenching nightmare to own over the last 20 years. It traded below its previous all-time high on 94% of days during that period. On average, its stock was 26% below its high of the previous two years. It suffered four separate drops of 50% or more. It lost more than two-thirds of its value twice, and more than three-quarters once.

That's how the stock market works.

This chart shows when, and by how much, Monster stock was below its high of the previous two years. (Periods at 0% show when shares hit a new two-year high). Again, this was during a period when shares increased more than a thousand-fold:

It's hard to grasp how the best-performing stock of the last 20 years could spend the majority of that time with returns that would make you want to vomit. It's easy to think that the single-best investment to own is one that would make us smile every morning we woke up owning it.

But it wasn't. It never is. And it never will be. That's the nature of the stock market. On the way to making serious money, you spend a lot of time losing serious money. It's a reality anyone investing in stocks, no matter what you own, has to face.

I looked at the 10 best stocks to own over the past 20 years. These are all cherry-picked for their stellar returns, and the stocks you would probably choose to own if you had a time machine. On average they increased more than 28,000%.

But they all spent a majority of the time well below their previous high mark. They all had multiple declines of 50% or more. A few had multiple 70% drops.

Take Biogen (NASDAQ: BIIB). It was the second-best stock to own over the past 20 years, increasing 60,210%. But most of the time, shares have been in some stage of pure agony:

Or consider Gilead Sciences (NASDAQ: GILD). It increased 21,000% over the last 20 years. But shares spent more of that period down 30% or more than they did anywhere near a new high:

Here's how it stacks up for the 10 best stocks to own over the last 20 years. Basically, it's a disaster:

There are a few takeaways here.

Stories change, and nothing is perfect. It's easy to think of Starbucks over the last 20 years as a story of uninterrupted success. We know where it began and where it is today, so that story makes sense. But so much happened in between. Growth slowed, plunged, and spiked again. It fired a CEO. Smart people wrote it off with analysis that made sense. It had to reinvent its growth plans, struggled with the introduction of food, and had trouble expanding overseas. What now looks like a slam-dunk story was, at any given time in the last 20 years, an easy story to criticize. That's why shares were so volatile.

Investors underestimate how common and severe volatility is, especially among individual stocks. If stocks with the cherry-picked best returns spend a third of their time down at least 30%, you can imagine what the long-term losers look like. It's a horror show.

There are two ways to deal with that: Accept severe volatility as normal, or blunt it with mass diversification. If you're OK with it, you can't remind yourself enough that huge volatility does not preclude high returns over time. It is a normal, inevitable part of the process. Capitalism is fierce about denying you something for nothing, and higher returns tend to demand the mental agony of higher volatility.

Accepting this, even at the whole-market level, is the name of the game. In 2009, Charlie Munger was asked how concerned he was that Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK-B) shares — which made up most of his net worth — dropped more than 50%. He quickly interrupted the interviewer and responded:

Zero. This is the third time that Warren [Buffett] and I have seen our holdings in Berkshire Hathaway go down, top tick to bottom tick, by 50%. I think it's in the nature of long-term shareholding that the normal vicissitudes in markets means that the long-term holder has the quoted value of his stocks go down by, say, 50%.

In fact, you can argue that if you're not willing to react with equanimity to a market price decline of 50% two or three times a century you're not fit to be a common shareholder, and you deserve the mediocre result you're going to get compared to the people who can be more philosophical about these market fluctuations.

Sums it up pretty well.

For more: