Start-up Carbon, previously known as Carbon3D, commercially launched its much anticipated first 3D printer, the M1, on April 1. The printer targeted at enterprise customers is powered by the company's potentially game-changing Continuous Liquid Interface Production (CLIP) 3D-printing technology, which has been demonstrated to be super-speedy and can reportedly produce production-quality polymer parts.

One of the most unique things about this launch is that the M1 will be available to customers via a subscription-pricing model -- a 3D printing industry first. After giving some background, I'll talk about why this pricing model is a brilliant move that could help Carbon capture business in an environment where the industry's largest players, 3D Systems (DDD 4.45%) and Stratasys (SSYS 4.22%), are struggling.

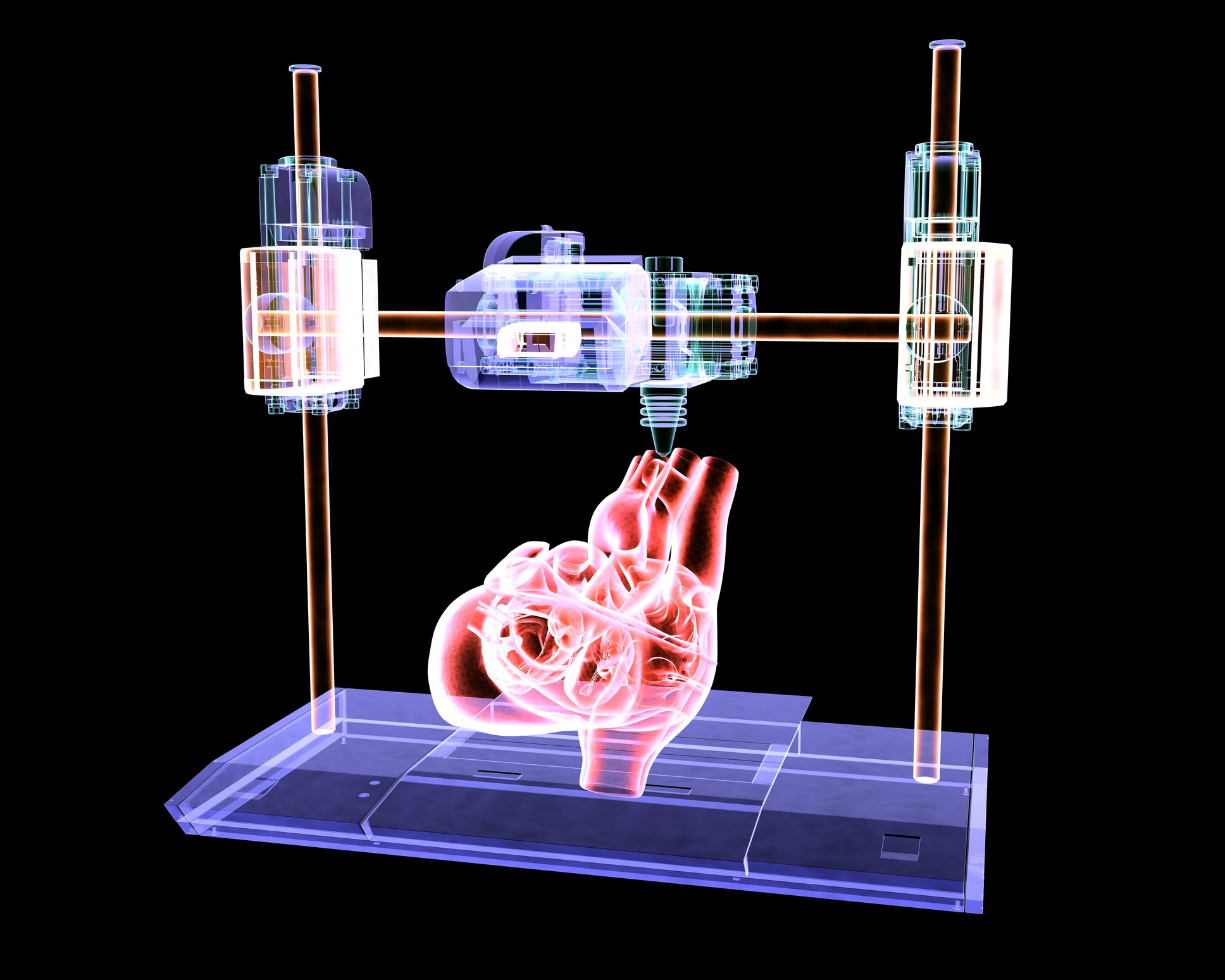

Image source: Getty Images.

Carbon and CLIP

Carbon, founded in 2013, wowed the tech world last March when co-founder and CEO Joseph DeSimone unveiled and demonstrated CLIP at the 2015 TED conference. Things have since moved fast, with the company's total funding now over $140 million. Backers include top venture capital firm Sequoia and big-name tech players Google Ventures (Alphabet's venture capital arm) and Autodesk. Early customers include Johnson & Johnson and Ford, with former Ford CEO Alan Mulally joining Carbon's board last spring.

CLIP was reportedly 25 to 100 times faster than the leading 3D-printing technologies PolyJet, selective laser sintering (SLS), and stereolithography (SLA) when tested last year to produce the same 51-millimeter-diameter complex part. This speed advantage results from CLIP "growing" polymer parts continuously, via harnessing UV light and oxygen, whereas other commercialized 3D-printing techs pause briefly after each layer is printed. Just as important, CLIP reportedly has immense materials possibilities, can produce objects with smoother surface finishes than conventionally 3D-printed parts and, thanks to its continuous production process, with structural consistencies on par with injection-molded ones.

CLIP has the potential to disrupt the manufacturing sector, as speed, materials capabilities, surface quality, and structural integrity are widely considered the top hurdles holding 3D printing back from moving beyond prototyping and select very short-run production applications into a greater array of manufacturing applications.

While the tech is garnering many accolades, there are skeptics. Terry Wohlers of Wohlers Associates, a top 3D-printing insights and consultancy firm, has expressed concerns about CLIP to Bloomberg and other outlets.These center around the tendency of plastic parts produced by the existing commercialized technologies that also use UV light in their processes (SLA and PolyJet) to degrade over time, particularly due to exposure to light. It's a legitimate issue about processes that use UV light, in general, but I'd not pay it too much heed regarding CLIP at this stage. CLIP is, indeed, a close cousin of SLA, though there are meaningful differences and technological advances can certainly occur in decades-old technology.

According to Bloomberg, "DeSimone says his unique processes help, not hurt, the finished product, especially the way Carbon mixes its plastics from distinct components just before printing. This makes them stronger, he says, because they finish binding together after they've been hit with the UV light." DeSimone is considered a leading authority on polymer chemistry. He's on leave as Chancellor's Eminent Professor of Chemistry at UNC-Chapel Hill and Distinguished Professor of Chemical Engineering at North Carolina State University, and held 150 issued patents at this time last year. This isn't to say there are any guarantees -- nobody can know for sure yet how these parts, which are being rigorously tested, will hold up over time. But this isn't a horse I'd bet against.

Carbon's M1

Image source: Carbon.

The M1 is an Internet-connected 3D printer with a build envelope of 144 w x 81 d x 330 h millimeters -- equivalent to about 5.7 x 3.2 x 13 inches. Carbon is touting the M1 as ideal for functional prototyping and low-volume manufacturing applications. Parts produced by the M1 reportedly have the mechanical properties, resolution, and surface finish needed for production applications.

The M1 is about software as much as it's about hardware, which will benefit Carbon and its customers. Offering Internet-connected printers allows Carbon to monitor more than 1 million data points produced by each printer in a day. If an issue is detected, Carbon can send out software fixes, just as it can send out software updates -- very Tesla-like. This model will help improve and speed up the development of the M1 and future CLIP-powered printers.

The company also launched seven novel resins, including a rigid polyurethane, an elastomer with spring-like properties, and a tough resin that can reportedly withstand temperatures of up to 426 degrees Fahrenheit.

Its speed relative to leading 3D-printing techs? Impossible to say. Carbon introduced proprietary resins that nobody else offers, so comparison tests aren't possible. The takeaways on speed, for now, are that CLIP has been demonstrated to sport a considerable speed advantage over leading 3D-printing techs and that the speed advantage will vary depending upon factors such as material and part complexity.

Carbon's industry-first subscription pricing is a great move

The basic M1 subscription package, including software and support, is priced at $40,000 per year, with a minimum three-year term. On-site installation and training is $10,000. The initial accessory pack (required, unless customers already own the items) will run $12,000. Customers get a huge deal if they subscribe to more than one build platform.

The benefit of the subscription-pricing model to customers, according to Carbon's website, is that it "reduces the overhead involved with capital equipment purchases and the complexity that often comes with the additional service agreements. It makes it possible for customers to leverage CLIP now, without losing the ability to upgrade as new products are released."

This pricing model is a terrific move -- at least initially. (It's possible some customers will eventually want to own their systems.) It should help increase adoption of 3D-printing tech among those companies that have been sitting on the fence due to the high initial upfront costs. It also removes what has likely been, in my opinion, one reason 3D Systems and Stratasys have experienced a significant slowdown in demand for enterprise 3D printers since the start of 2015: the reluctance among some companies to make huge capital expenditures for a 3D printer -- which can reach well into six figures -- because of concerns that it might too soon be outdated by newer technology.

It's impossible, of course, to be certain as to all the factors at play in this slowdown -- and their degree of importance. Stratasys has attributed the weak demand to overcapacity in the field due to the large number of printers purchased during the previous few years. It seems probable that this explanation accounts for the bulk of the slowdown, but it's possible -- even probable -- that at least some companies are delaying their buying decisions due, indeed, to concern that they'll be stuck with pricey tech that's not the best fit for their needs. It's been well known that Carbon and HP Inc. planned to launch 3D printers with reportedly compelling features in 2016, and other large companies, such as Canon, also plan to enter the space.

Final thoughts

While I believe Carbon's subscription-pricing model is a fantastic move -- at least initially -- we'll have to wait to see how it plays out. More important, we'll have to wait to see how satisfied customers are with parts produced by the M1 over the long term, though early customer feedback is very positive.

CLIP has disruptive potential. Even if it turns out to be a humongous winner, however, it's highly unlikely that one 3D-printing tech will ever be the best fit for all applications involving polymers. CLIP, for instance, cannot produce multimaterial objects, a capability that some customers will probably continue to desire for the final stage of prototyping. Stratasys and 3D Systems make printers with such capabilities, with Stratasys' Connex printers particularly favored in this space.

Carbon is moving fast, which isn't surprising given the combination of DeSimone's background (both technically and in putting together and leading teams) and its A-Team backers. If CLIP's promise is even just partially realized, 3D Systems and Stratasys will need to play at the top of their games with respect to innovation and execution if they want to remain the top dogs in the 3D-printing space.