After suffering more than two years of declining or low oil and gas prices, the financial statements of energy companies have been absolutely ravaged. Cash flows have dried up, balance sheets have been ballooning with debt, and more than a few companies have filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Even the once-impregnable dividends of the integrated majors have looked more troubled than they have in more than 30 years.

Needless to say, in a cyclical industry like oil and gas, there are fortunes to be lost and fortunes to be made. The companies that can come out the other end of this major decline could have an immense opportunity to profit as declining investment in the industry could easily bring supply and demand in line once again.

Image source: Getty Images

With all of these key facts in mind, investors are likely to benefit from looking closely at the integrated majors. Their size, diversified business models, and propensity to pay a regular dividend in this boom-and-bust industry can make them intriguing prospects. As much as they are alike, though, there are subtle differences among them that investors should be aware of before diving in. Let's take a long look at these monolithic energy companies to determine which one is the best investment today.

The usual suspects

Typically the term "big oil" refers to companies that have a few distinctive traits: They have assets in every part of the oil and gas value chain; their production levels are measured in the millions of barrels per day; and their respective market capitalizations are huge -- we're talking $100 billion or more. Based on these criteria, there are always five companies that are mentioned: ExxonMobil (XOM +3.98%), Chevron (CVX +2.44%), Royal Dutch Shell (NYSE: RDS-A) (NYSE: RDS-B), BP (BP +2.90%), and Total (TOT +0.00%). For argument's sake, though, let's add one more integrated company into the mix, Italian oil producer Eni SpA (E +1.75%).

There are a couple other companies that we could add to this list, such as PetroChina and Petrobras, but they are a little harder to evaluate purely as investments because they have heavy investment from their national governments. In the best-case scenario, the interests of the state may not be 100% in line with those of shareholders. At worst, financial reporting from the company may be deliberately opaque and not completely reflective of the situation on the ground. Eni does count the Italian government as a major investor, but it hasn't employed some of the heavy-handed policies that the Brazilian and Chinese governments have on Petrobras and PetroChina, respectively

There are the typical metrics to look at when evaluating these companies -- margins, cash flow, returns, valuation, etc. -- but the current two-year low in oil prices isn't exactly normal times. So in addition to the typical signs you want to see in these companies, let's also take a look at how they have responded to the decline and how it might impact their future.

Margins and returns

| Company | Gross Margin (Current) | Gross Margin (10-Year Avg.) | EBITDA Margin (Current) | EBITDA Margin (10-Year Avg.) | Net Income Margin (Current) | Net Income Margin (10-Year Avg.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | 14.6% | 15.7% | 8.4% | 10.9% | (2.8%) | 3.5% |

| Chevron | 30% | 30.5% | 14.1% | 18.2% | (0.7%) | 8.2% |

| Eni | 17.7% | 26.3% | 12.3% | 22.4% | (20.2%) | 2.5% |

| ExxonMobil | 42.7% | 35.7% | 12.2% | 15.8% | 5.1% | 9% |

| Royal Dutch Shell | 15.2% | 16.4% | 7.4% | 11.3% | (2.1%) | 4.6% |

| Total | 33.6% | 32.7% | 14.9% | 18.3% | 2.5% | 6% |

Data source: S&P Global Market Intelligence.

There is no way to look at these results without having to hold your nose, but then again, that is what is going to happen when oil prices steadily decline for more than two years. The past 12 months have been some of the most brutal for any company with exploration and production assets. While all of the companies here are integrated companies that have assets in production and refining, the fact of the matter is that all of them were generating the lion's share of their profits from production over the years.

Some companies have fared better than others, though. As the table above shows, both ExxonMobil and Total have managed to maintain positive net income margins over the trailing 12 months while the rest have dipped into the loss column. Total, in particular, has offset the declines in prices with a huge uptick in production from lower-cost sources such as its operation contract with the Abu Dhabi Company for Onshore Oil Operations (ADCO).

ExxonMobil, on the other hand, has mostly kept on doing what it has done for decades. It avoided some of the unprofitable pitfalls that others succumbed to because the price at which the company assessed new projects was much, much lower than the price its peers used. As recently as 2014, Chevron, Shell, and BP were building their capital budgets with oil around $70 a barrel, while ExxonMobil's budget was based on oil at $55 a barrel. Staying conservative then is clearly helping profits now.

The other big outlier here is Eni's ghastly net income margin. I'm sure that management wants to chalk that up to the $4 billion in asset writedowns it took over the past 12 months, but that doesn't tell the whole story as the company's gross profit margins have declined the most in the group. Since asset writedowns aren't included in the gross margin calculation, clearly there were some cost issues that have hampered the company lately.

Keep in mind, though, that profits don't always correlate with generating returns. So to double-check those profitability results, let's look at all of these companies on a return basis. Also, instead of being easy on them with a simple return-on-equity calculation, let's use the DuPont return-on-equity calculation to see if something fishy is hiding in those returns by breaking them down into their components and multiplying them together. This graphic describes the components:

Image source: Author.

Data source: S&P Global Market Intelligence. Chart by author

It's hard to evaluate a company when its EBIT margins (that is, before interest and taxes) are negative using this method. It throws off metrics like interest burden and tax efficiency. So for now, let's just look at the two companies with positive pre-interest, pre-tax margins: ExxonMobil and Total. While ExxonMobil does a slightly better job of generating sales from its assets and is less burdened by interest, Total's higher EBIT margins -- and a little bit of tax relief -- gave the company a slightly better result. That's no small feat considering that ExxonMobil has been the leader of the pack in terms of return on equity for decades and even has a bit of an unfair advantage in this metric because it has bought back so much stock over the years that its book equity value is well below its market value.

We can even double-check this win for Total with management rate of return. This is earnings before interest and tax, divided by total property plant and equipment -- net of depreciation -- and total working capital. It's a more accurate measure of how effectively management allocates capital.

| Company | Management Rate of Return |

|---|---|

| BP | (1.17%) |

| Chevron | (3.6%) |

| Eni | (4.14%) |

| ExxonMobil | 2.35% |

| Royal Dutch Shell | (4.65%) |

| Total | 5.67% |

Data source: S&P Global Market Intelligence,

We can see pretty clearly here that Total has arguably done the best job at managing this downturn. ExxonMobil is in second place as it is the only company that has been able to maintain positive margins and returns recently. The one company that has done a surprising job on this end is BP. This time last year, the company was the worst-performing of the group in terms of margins and returns, but that was in part because it was much more aggressive at writing down its assets and taking losses related to the litigation following its 2010 Gulf spill. With fewer writedowns and some pretty impressive cost-cutting measures, BP seems to be on the rebound.

1. Total

2. ExxonMobil

3. BP

4. Chevron

5. Royal Dutch Shell

6. Eni

Cash flow (or in this case, lack thereof)

| Company | Levered Free Cash Flow (Current) | Levered Free Cash Flow (10-Year Avg.) |

|---|---|---|

| BP | 2.6% |

2.6% |

| Chevron | (7.8%) | 0.2% |

| Eni | (0.7%) | 2.6% |

| ExxonMobil | 0.2% | 4% |

| Royal Dutch Shell | (2.2%) | 1% |

| Total | (2.3%) |

2.7% |

Data source: S&P Global Market Intelligence.

If 2015 looked bad from a cash flow perspective, this year looks downright atrocious. The big standout here is Chevron, the company that has struggled the most with cash flow over the past couple of years as it has been spending loads of money on its Gorgon and Wheatstone liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities. These two alone represent a significant amount of the company's total assets, and Gorgon just barely started doing test LNG cargoes this year.

The two that have changed the most over the past year have been BP and Shell, but for opposite reasons. Now that Shell has completed the acquisition of BG Group, it has also taken on its spending habits. As the company works through the integration process and divests some of the parts of the business it no longer wants, we can expect this metric to go down, but for now it has hit the company pretty hard. BP, on the other hand, has shown it took its cost-cutting and capital spending seriously. Part of the turnaround in cash flow had to do with the company's lowering its working capital obligations, either through completing projects or divesting them.

It should be noted, though, that some of those gains in levered free cash flow came from asset sales gains. If we look at operational cash flow as a percentage of capital spending -- a more accurate gauge of the company's cash-generating abilities from its continuing operations -- the one company that is still able to cover all of its spending obligations is ExxonMobil, with the rest going into significant cash-burn mode.

| Operational Cash Flow as a Percentage of Capital Expenditure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | Last 12 Months | FY 2015 | FY 2014 | FY 2013 |

| BP | 92% | 103% | 145% | 86% |

| Chevron | 56% | 66% | 89% | 92% |

| Eni | 91% | 104% | 141% | 101% |

| ExxonMobil | 107% | 114% | 137% | 133% |

| Royal Dutch Shell | 79% | 114% | 142% | 101% |

| Total | 80% | 79% | 97% | 96% |

Data source: S&P Global Market Intelligence. Less than 100% means more cash spent than generated. FY = fiscal year.

This is important because almost the entire value proposition of owning integrated oil and gas companies centers on their tendency to produce steady returns through their ability to pay solid dividends and buy back shares to increase per-share earnings results. With only Exxon able to even cover its capital spending, some question its ability to pay dividends. Shell, BP, and Total have all enacted scrip dividend programs that allow investors to take dividend payments in newly issued shares rather than cash to reduce cash outlays, and Eni even cut its dividend by 29% in March 2015 to preserve cash.

A lot of these cash woes go back to the budgeting assumptions mentioned earlier, and it's pretty clear from these results that ExxonMobil is doing the best of the group here. BP is certainly looking better lately and gets second place. Shell gets a bit of an incomplete grade because of the BG merger. Perhaps we can give this area a better look after the company has had a year to digest this acquisition.

1. ExxonMobil

2. BP

3. Eni

4. Total

5. Royal Dutch Shell

6. Chevron

Steps to preserve today...

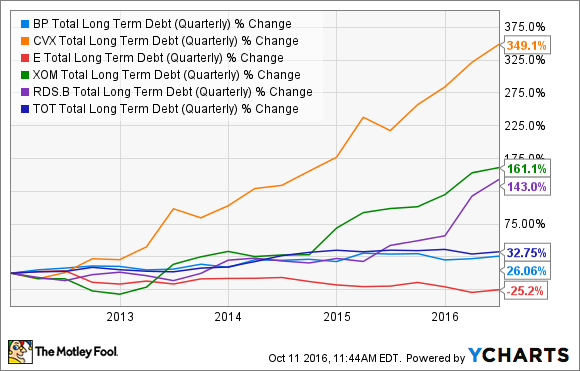

Just about every company here got caught off guard when oil prices started to decline. As the cash flow numbers suggest, all of them have had to do something to fill in the spending gaps. While some have relied more on asset sales (Eni, BP, Total), others have dipped into the debt markets rather heavily.

BP Total Long Term Debt (Quarterly) data by YCharts.

This approach, however, is in no way sustainable, and these companies have reacted by taking out the machete to their capital spending budgets over the past two years.

BP Capital Expenditures (TTM) data by YCharts.

This move has helped to a degree, but it hasn't been enough to heal all of these companies' wounds. The debt levels have put these companies a little out of their comfort zones, as most of them have seen their credit ratings take a hit.

There are two factors that can fix this: higher commodity prices or continued lower spending rates. Eventually, the former will happen, as production levels in the U.S. have declined, OPEC seems to be on board for a production cut, and demand continues to rise. Chances are, though, we won't be seeing $100-per-barrel oil again any time soon. So let's see what each company has in mind for its capital spending over the next few years.

BP

BP was actually one of the first companies to start really thinking about lowering its costs and being a little more selective about the types of projects in which it was investing. That decision wasn't because of management's foresight, though. Rather, it was in preparation for the high costs -- tens of billions of dollars -- related to the Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010. The company had to radically change the way it was spending on new projects. As CEO Bob Dudley put it at the time, the company needed to stop growing production for the sake of growing production and focus more on the returns for each barrel it took out of the ground. As a result, BP sold off several billions of dollars of assets, and that is why the chart below shows cash costs starting to lower in 2012.

One of the reasons that the company didn't really reap the benefits of this cost-cutting effort during the recent downturn was that it was still giving the green light for projects with some very optimistic outlooks for oil prices. As recently as last year, BP was assessing new projects under the assumption of Brent crude oil in the $80-per-barrel range with a "stress test" of $60 a barrel. Even more surprising was that it foresaw oil prices rising back to the $100-a-barrel range by 2020.

That line of thinking has been thrown out the window, though, and now the company is taking a more conservative approach, as the chart below shows.

Image source: BP investor presentation.

With a capital spending budget between $15 billion and $17 billion at least through 2017, the company is estimating that it can cover its dividend and capital spending needs with oil in the range of $50-$55 per barrel of Brent crude. With oil prices hovering around this level lately, BP should start to turn the corner in terms of profitability and build on the improved cash flow situation that it has shown in the past 12 months.

Chevron

Chevron has been one of the slowest companies to adjust its spending levels to the new reality of lower oil prices. The reason is that it has been trying to put the finishing touches on its Gorgon and Wheatstone LNG projects for several years now. These two megaprojects are unique because Chevron holds such a high working interest in them. In the long run, that could pay off as the company will get the lion's share of the profits, but today it means that Chevron is responsible for shelling out mountains of cash to build and complete the projects. In 2015, Chevron's management said that spending on Gorgon and Wheatstone was $8 billion a year, about one-quarter of all the company's spending requirements for the year.

Once those two facilities come on line, though, management is looking to make up for lost ground by drastically reducing its spending levels in 2017 and 2018 to around half of what they were in 2014. This is part of the plan the company has in place to become cash flow neutral in 2017, come hell or high water.

Image source: Chevron investor presentation.

It's hard to say whether Chevron will be able to make good on this promise. As recently as 2015, that cash-flow-breakeven promise was made with an assumption of Brent crude remaining around the $70-per-barrel range, so a lot of commissioned projects were built around the idea of much higher prices. Management has since revised that level down, but to do so, it plans to sell several billion dollars of assets to get there. If oil prices were to remain where they are today, then chances are Chevron's cash flow situation will remain rather tight for the coming years.

Eni

Eni has been in a unique position recently. Over the past five years, the company has found an immense amount of oil and gas in places like off the coasts of Egypt and Mozambique. While it would like to reduce spending as much as the other integrated oil and gas companies, some of these opportunities are simply too good to pass up. That is why the company decided to cut its dividend last year and commission large projects, like the Zohr project off the coast of Egypt, rather than cut capital spending to the bone and preserve its dividend.

There is another reason that Eni is using this tactic: It wants to monetize some of these massive assets by selling working interests in them. Zohr, for example, is 100% owned by Eni. At 30 trillion cubic feet of reserves, it is one of the largest gas discoveries in recent years, and field production is expected to be around 400,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day in dry gas production. The total price tag for the project is $12 billion today, something that will be hard for Eni to fund on its own. So it plans to sell a working interest in the project -- ExxonMobil is rumored to be interested -- that will bring in a large chunk of cash that can be used to fill spending gaps or even to pay down some of the debts the company built up during this downturn.

Image source: Eni SpA investor presentation.

Of the companies in this group, Eni is probably the one most focused on playing the long game. Its capital spending in relation to its size will be a little higher than those of the other companies on this list, but the payoff should be that it will be in a better place four or five years down the road with its suite of projects.

ExxonMobil

For decades, ExxonMobil has been known as the lighthouse in a stormy sea for oil and gas investors. No matter what part of the cycle the industry found itself in, ExxonMobil's management would keep its spending levels relatively stable throughout the cycle. That is what makes the company's plan for the next several years so surprising. Based on management's plan, capital spending for 2016-2020 should be about 40% of what it was in 2014.

Right now, it's hard to see if this is a radical change in the company's long-standing policy of consistent investment or if the last three to five years, during which it spent uncommonly large amounts of money, have been the exception. After all, management said in 2013 that it would be the year of the highest level of capital spending, and the company has pretty much followed that track all the way to this year's capital budget.

Image source: ExxonMobil investor presentation.

One example supporting the idea that the last few years were the exception is the company's chemical and downstream investment. Despite the rapid decline in overall spending, the amount going to downstream and chemical projects has remained surprisingly consistent.

One advantage that ExxonMobil has over the other companies discussed here is that the price level at which it has been assessing new projects over the past few years has been much more conservative than that of others. In 2015, management's breakeven-price assumption was in the $55-per-barrel range. As oil prices go up, ExxonMobil's upstream profits should start to recover relatively quickly as these lower-cost sources come on line. It also helps that the company hasn't had to tap the debt market as extensively as some of its peers over the past few years, so it should be able to get back on track much faster than some of the others.

Royal Dutch Shell

Shell is by far the biggest wild card when it comes to what it will do in the coming years. The addition of BG Group to its portfolio certainly gives the company lots of opportunities to spend money on new projects, but the reality is that it would be incredibly difficult to justify spending money on all of them. That is why Shell is in the middle of a large asset turnover that will involve selling $36 billion-$38 billion in assets between now and 2018. Basically, the company is acting like a chop shop for the two business portfolios, combining the overlapping and complementary businesses, and jettisoning the remaining ones. As a result of this plan, Shell's long-term planned spending will be lowered to $25 billion-$30 billion annually.

Image source: Royal Dutch Shell investor presentation.

It should be noted that Shell's spending plan is the largest among all the integrated companies. A lot of that has to do with the fact that Shell is making a large push into LNG. By the end of 2018, the combined portfolios of Shell and BG Group will produce 45 million tons of LNG per year, which is more than double the LNG portfolio of its closest peer, ExxonMobil. Shell estimates that when these facilities come on line, they will easily cover its capital spending and generate $20 billion to $25 billion of free cash flow from 2019 to 2021, with oil around $60 per barrel.

The biggest unknown for investors of Shell is how this whole asset shuffle plays out. Asset prices in the energy industry are still low, so it's questionable whether the company can generate that desired $35 billion in sales from the assets it wants to part ways with. This could be a determining factor in whether it can meet those free cash flow numbers.

Total

Like BP, Total has been one of the few companies that was able to get out in front of the decline in oil prices with declines in capital spending early. It was able to do this because a large portion of its projects under construction were completed in 2015 and the first half of 2016. This had the double effect of reducing capital spending and bringing on more production that was generating cash. I'm sure there is someone in management at Total patting themselves on the back for reducing spending at just the right time, but it's probably closer to the truth that the company got lucky as to when the bulk of its spending was coming to an end.

With a modest capital spending program slated for the rest of the decade, Total estimates that it will be able to generate considerable free cash flow with oil prices in the $60-per-barrel range out to 2020. While $60 sounds a little high by today's standards, it is reasonable to assume that keeping breakeven prices at or below that number all the way to the end of the decade should do rather well for the company. Contingent to meeting this goal, though, is Total's ability to start up its Yemen LNG facility. With civil conflict having unfolded there for several years now, it's hard to say whether that start-up is a certainty.

Image source: Total investor presentation.

Based on these management assessments, the ranking of the companies' appeal is going to come down to one's personal market outlook for the next several years. Shell and Eni are keeping investment levels higher, which means that they are more reliant on higher oil prices in the near future, whereas ExxonMobil, BP, and Total are taking a little more conservative approach over the next few years, which would be better-suited for a slower recovery in oil prices. Chevron wants to be in the more conservative camp, but it is still working on finishing up some legacy costs that will continue to keep free cash flow levels low for a while. I also can't give a final verdict on Eni since it is trying to sell off some working interest in some of its most lucrative assets. Once we have an idea of how much of its interest it sells and the sticker price it gets, then we can give it a better verdict

Personally, I'm in the camp that believes the recovery in oil prices is going to be slow, and that taking a slightly more conservative approach will be rewarded over the next three to five years, so I'm a little more attracted to the plans from BP, ExxonMobil, and Total. In all honesty, though, I still want to see more progress from Shell on its asset turnover before I issue a final verdict on this particular company

1. ExxonMobil

2. BP

3. Total

4. Chevron

5. Eni / Shell (incomplete)

...while keeping an eye on the horizon

The thing with capital spending is that when it gets cut, it is at the expense of longer-term opportunities. For all of these companies, a large chunk of cuts in their capital spending came from reductions in their exploration budgets. Over the next three to five years, this isn't a big deal, but it will really start to show further down the road. So as a countercheck to looking at each company's efforts to handle the downturn, let's also look at its asset portfolio and what kind of work it will have for the next decade and beyond to see if there is plenty of work to maintain or grow production.

BP

BP's production over the next several years is tied to three major projects: its Khazzan gas project in Oman, the Shah Deniz gas field in the Caspian Sea, and an offshore Egyptian natural gas field very similar to Eni's Zohr discovery. Between now and 2020, these three projects are going to represent the bulk of BP's production growth, which is projected to be 800,000 barrels per day of oil equivalent.

The biggest concern with having all its eggs in so few baskets is that there is some risk if there are any issues with any of the projects, and some of them have a very high degree of difficulty. For example, the Shah Deniz gas project is so complex that the budget includes building a pipeline through several countries, and even setting up welding schools to train local workers to meet demand.

Image source: BP investor presentation.

If we look further into BP's future, we see that much of its development over the years is very concentrated on a few projects that have massive potential. On top of those three projects that will be implemented in multiple phases over the next decade or so, the company also has some large finds off the coast of India that have great potential. Again, this is a pretty concentrated portfolio.

The one solace, though, is BP's equity investment in Russian oil giant Rosneft. Since it has an equity stake that gets an annual dividend, BP has no cash spending obligations on this investment. Rosneft's size and access to some of Russia's most lucrative oil and gas fields could be a very good thing for BP in the long term.

Chevron

Over the next half-decade or so, Chevron's production growth is going to be rather modest. The company estimates 0%-4% production growth annually between now and 2020. The wide range of projected production growth is due to Chevron's plan to make a significant pivot from large megaprojects to developing its portfolio of shale oil and gas. The economics for shale wells have improved drastically over the past several years, and it helps producers like Chevron that the time from when the drill bit hits the ground to when oil or gas begins to flow is very short.

Since it takes so much less time to bring these shale gas wells to fruition, Chevron is leaving itself quite a bit of wiggle room in its production rates to respond to oil and gas prices. If prices rise quickly, then the company will likely go full steam ahead with its shale assets across North America and Argentina, which will lead to more rapid growth. The rest of its portfolio, on the other hand, is larger-scale projects that will take some time to develop. With the lead time on some of those projects, it's difficult to see how much they will be able to contribute to growth.

Two projects that are really worth keeping track of are its Tengizchevroil Future Growth Project-Wellhead Pressure Management Project, in Kazakhstan, also called TCO FGP-WPMP on its investor presentation (really, Chevron, that was the best name you could come up with?), and its Kitimat LNG facility, in Canada. As with Gorgon and Wheatstone, Chevron holds a very high working interest in the two high-sticker-price projects. It just gave the green light for the $37 billion TCO project and is still evaluating Kitimat. Investors may want to keep a close eye on these two to make sure that Chevron avoids the pitfalls it faced with its most recent megaprojects.

Image source: Chevron investor presentation.

Eni

Eni has the highest-risk, highest-reward portfolio out there. The risk for the company is that many of the places where it has plans to explore for oil over the next several years don't exactly have reputations as politically stable (Libya, Nigeria, Pakistan, Myanmar), don't have great relations with the West (Russia), or have very limited oil and gas infrastructure in place (Mozambique, Pakistan, Ghana). If there were to be a political unraveling in any of these countries, then much of Eni's asset portfolio would be untouchable for many years to come.

The upshot for Eni is that many of these potential assets are massive fields that could sustain production growth for decades. Its Zohr project I have mentioned a couple of times is just one example of some of the large finds.

Based on its capital spending budget now, Eni will be able to grow production at a decent clip of 3% or better annually. That rate of growth -- plus some injections of cash from farming out interest in some of these longer-tail projects, as well as rising oil and gas prices -- could be a pretty strong cash flow platform from which the company should be able to invest heavily in these new places. Again, though, much of that potential could come crashing down because of the higher-risk nature of its portfolio.

Image source: Eni investor presentation.

ExxonMobil

Of course ExxonMobil has the largest platform of potential projects over the next several years because, well, it's the biggest integrated company out there. According to its most recent analyst day presentation, Exxon had a potential resources portfolio of more than 90 billion barrels, enough to provide it with a couple of decades' worth of production. Granted, not all of those potential resources will make it to the development stage, but the company still has plenty of irons in the fire.

Image source: ExxonMobil investor presentation.

Like Chevron, ExxonMobil is leaving quite a bit of wiggle room in its production rates over the next several years, and its final moves will depend largely on the economics of shale oil and gas. The actual production growth rates between now and 2020 are rather modest -- 400,000-600,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day -- but the big thing Exxon is looking to do over this time frame is to replace production from some of its sources with lower rates of return and upgrade them with higher-return projects. An example is its recent acquisition of some very lucrative natural gas fields in Papua New Guinea that will allow it to expand its existing LNG facility there and its 2-million-plus acres of shale assets in the Permian Basin and Bakken formations in the U.S.

Royal Dutch Shell

It is hard to judge Shell over the long term because of all the asset sales that are going to take place. If it were to keep its existing portfolio in place, then its growth plans would be the largest in the business, with 1.2 million barrels per day in growth as well as 15 million tons per year in LNG. However, much of those gains will be used to offset the company's asset sales.

Image source: Royal Dutch Shell investor presentation.

Beyond that, Shell is also keeping a large quiver of development projects in play that will give it plenty of resources in the future. Unlike Chevron and ExxonMobil, though, Shell is focusing heavily on deepwater projects with an emphasis on the Gulf of Mexico and off the shores of Brazil. On the surface, this would be a good thing because it ensures that Shell will have plenty of new production over the next decade or more. One thing to keep in mind, though, is that Shell doesn't exactly have a reputation as a high-return company. For years it had a reputation as the company willing to take on the risks of exploring and developing higher-cost projects. Its high-risk approach was one of the reasons that it was one of the last companies to cancel its Arctic exploration program. Many of Shell's new assets are in places where marginal costs are higher, and making the economics of the projects work requires finding massive fields.

Shell CEO Ben van Beurden has said that the company is trying to shed this reputation and focus heavily on better returns, with a target of 11% return on average capital employed for its new production. The recent decline in oil prices helps in that Shell is getting much more favorable contract rates for some of these projects, which will increase returns over the long run. However, this hasn't historically been the norm for the company, and investors will want to see results to back up management's claims.

Total

For all of the winding down of spending at Total over the past 18 months, the company still has quite a bit of production growth left in it for the rest of the decade. Management estimates that production will grow 4% annually between now and 2020. Beyond that, things will start to slow down, with growth in the 1%-2% range post-2020. But take any such long-term production projections with a grain of salt, because the changing dynamic of oil prices could also result in a change in spending habits.

The good thing is that the company has a decent portfolio to work off of over the next several years. A lot of it is levered to LNG, with investments in Yamal LNG in Russia, Ichthys LNG in Australia, and a potential LNG terminal in Papua New Guinea that Total has been mulling over for years.

Image source: Total investor presentation.

The big critiques for Total's future portfolio are, first, that it's a bit concentrated on a single area, with a large development platform in offshore West Africa; and second, that those potential sources carry higher costs. Total has offset some of these higher-cost sources lately by bidding on -- and winning -- commission contracts with Middle Eastern countries to develop their reservoirs, which provide lower-cost, low-risk additions to the portfolio. If it can continue to offset its higher-cost production portfolio with lower-cost commission contracts, then it should be able to achieve growth levels that are better than its projected rates. The one thing to consider, though, is that there is an "if" statement in there that can really change things if things don't go Total's way.

All in all, there is actually a lot to like from this group. Chevron and ExxonMobil probably are in the best position because they have the most options in the future between shale and their plethora of other projects. The rest of the companies in the group are a little more levered to the success of offshore and LNG projects -- endeavors with a longer development cycle and higher cost. If Chevron were to lower its working interest in the Kitimat LNG and bring the TCO project to fruition on time and on budget, then it might get a little lead over ExxonMobil because of its massive shale resources. However, Chevron's execution on these megaprojects hasn't been top-notch, so the company gets a little deduction there.

Eni probably has the most upside, but it is important to remember that there is a lot of risk there. Royal Dutch Shell's options look pretty attractive, but its prospects are contingent on the company's ability to get better at lowering costs over the long term and on receiving a little help from higher oil prices because of the higher-cost nature of its projects. The one beef with BP is that its portfolio is so concentrated that if one of those projects gets nixed, it would result in a major setback. The only thing that offsets that danger is the massive possibility with Rosneft. Total gets knocked down a few points because its future portfolio success is contingent on winning those commission contracts. If other major players here were to start aggressively going after these contracts as well, Total's long-term future would suffer a decent-size dent.

1. ExxonMobil

2. Chevron

3. Eni

4. BP

5. Royal Dutch Shell

6. Total

Valuation

It's one thing to buy a stake in one of these companies, but it's a whole other thing to buy shares at a price that will actually generate a return for you over the long term. Oil and gas is a cyclical business, and as many of us learned in 2014, it can take a long time to recover from a poorly timed position in this industry. Also, in the context of a cyclical industry, valuation metrics might not tell you the entire story. You have to look at the valuation as well as where in the cycle this business is.

For example, a company at the top of the cycle might trade at low earnings-based valuation metrics as investors start to anticipate a decline in earnings. Conversely, a higher-than-average multiple at the bottom of the cycle doesn't necessarily mean that a company is expensive, because it's poised for a rapid increase in earnings. So let's keep this in mind when we look at the valuations for all of these companies.

| Current Valuation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | Total Enterprise Value/Sales | Total Enterprise Value/EBITDA | Price to Normalized Earnings | Price to Tangible Book Value |

| BP | 0.8 | 8.6 | N/A | 1.82 |

| Chevron | 2.2 | 12.7 | N/A | 1.36 |

| Eni | 1.1 | 9.9 | N/A | 0.97 |

| ExxonMobil | 2.0 | 13.3 | 48.3 | 2.12 |

| Royal Dutch Shell | 1.2 | 14.1 | N/A | 1.17 |

| Total | 1.1 | 6.9 | 19.7 | 1.34 |

Data source: S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Aside from the absolute lack of earnings-based multiples, shares of these companies look relatively cheap. The group's enterprise multiple (enterprise value to EBITDA) ranges from 7 to 14, which tells us some of these companies are great deals, relative to the broader market, and some have middle-of-the-road valuations. However, integrated oil companies typically sell at a discount to the broader market. So instead of looking at these valuations in a vacuum, here is each company's 10-year historical valuation, as a more apples-to-apples comparison.

| 10-Year Avg. Valuation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | Total Enterprise Value/Sales | Total Enterprise Value/EBITDA | Price to Normalized Earnings | Price to Tangible Book Value |

| BP | 0.61 | 4.96 | 22.7 | 1.53 |

| Chevron | 1.02 | 4.92 | 14.4 | 1.81 |

| Eni | 0.90 | 4.02 | 14.6 | 1.50 |

| ExxonMobil | 1.15 | 6.17 | 14.1 | 2.78 |

| Royal Dutch Shell | 0.64 | 4.99 | 11.9 | 1.47 |

| Total | 0.81 | 4.14 | 8.5 | 1.94 |

Data source: S&P Global Market Intelligence.

As you can see, all of these companies are trading at big premiums to their 10-year averages, according to their sales-, EBITDA-, and earnings-based valuations. That is to be expected, though, because we are at or very close to the bottom of the latest oil cycle. The one metric here that provides a little more consistent gauge is price-to-tangible book value, as it is a measure of how the market values the underlying assets that generate the profits, rather than the profits themselves. So I'm going to give a lot of weight to price-to-tangible book value.

Based on this analysis, Eni actually looks like the cheapest stock: It's trading at a pretty significant discount compared to its long-term average, and with a price-to-tangible book value of less than 1, the market says that its assets are worth less than their liquidation value. Total comes in second thanks to a decent price-to-tangible book discount, and its TEV-to-EBITDA valuation isn't that far above its historical average. As you might expect, both ExxonMobil and Chevron are selling neither at a screaming discount nor a massive overpay. The one surprising takeaway is that BP is currently trading for a decent premium in just about every category. Perhaps that is an indication that the market likes its shorter-term plan on cost-cutting, or maybe the stock is just a little too expensive to touch right now.

1. Eni

2. Total

3. ExxonMobil

4. Chevron

5. Royal Dutch Shell

6. BP

Just to recap, here is how all of the companies ranked based on each criterion.

| Company | Margins and Returns | Cash Flow | Short-Term Plan | Long-Term Potential | Valuation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Chevron | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Eni | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| ExxonMobil | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Royal Dutch Shell | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

What a Fool believes

The performance of big oil stocks over the past couple of years probably has left investors wanting for a bit more, but that is the name of the game when it comes to these cyclical businesses. There are going to be long periods of underperformance from time to time. This recent decline might even be considered a "super-cycle." The emergence of shale as an economically viable source of hydrocarbons and its decline down the cost curve has opened up billions of barrels of new resources. That discovery was possible because we had a very long period of high oil prices that allowed companies to invest in these unconventional sources. The current situation is very similar to the late '70s and early '80s, when sustained oil prices gave companies the financial incentive to start producing oil from deeper water reservoirs.

Eventually, the market will adjust for these cheaper sources and their impact on the overall market. The effect may push out some higher-cost barrels of oil and gas, but it isn't enough to completely upend the entire market. These arguments suggest that the window for buying integrated oil companies is still very much open. The flat or modest declines in consumption from developed markets will more than be offset by rising demand from emerging markets for many more years to come, so there is still a long runway to invest in hydrocarbons. Also, at today's prices, you can still get some decent discounts.

Based on the data here, it looks as though ExxonMobil has regained the top spot as the best big oil stock to buy. It isn't the cheapest stock by any means, but its cash-generating abilities are head and shoulders above the rest. In addition, it has lots of flexibility in its long-term outlook, whereas most of its peers have to have at least one or two specific things go just right over the next decade to play out.

Total is closest in second place, with Eni and Chevron within reach. Each is very close to the others in the second to fourth place, each with a distinct advantage over the others in one or two categories. Total got the final nod for the second-best investment because of its valuation and its strong rates of return.

For the investor who has a big appetite for risk, Eni may actually be worth a look. Its current profitability looks a little tough, but the company is sitting on loads of great assets that could be monetized in a lot of interesting ways

It seems that the window for buying these stocks at decent prices is getting shorter and shorter. OPEC has made some rumblings that it wants to focus on preserving oil prices rather than market share. Chances are that the increase in oil prices will be a long and slow one over the next several years. While sobering, this likely outcome also makes the chances that oil prices will head south in another downturn look less and less likely. If you have been thinking about adding one of these stocks to your portfolio, then you may want to act sooner rather than later.