Renewable power, like solar and wind farms, has been a hot space in the utility sector. Companies from large regulated utilities like NextEra Energy (NEE +1.75%) to upstarts like Clearway Energy (CWEN +1.95%) have jumped into the space. One of the key niches here is selling power under long-term contracts to others, which has been assumed to be a safe business. But PG&E's bankruptcy suggests that may not be the case. Here's what you need to know and why at least one big industry participant has shied away from building renewable power for others.

A great idea

There's no question that renewable power is hot today. The global warming issue in the headlines is a big push. But also driving the shift toward renewables are increasingly stringent environmental regulations and government mandates for "clean" electricity production. It should come as little surprise that renewable power has been one of the fastest-growing sources of electricity in recent years. It's also projected to be among the fastest-growing sources in the future, too.

Image source: Getty Images.

That's backed by an investment boom in the space. On one side of the equation are giants like NextEra Energy. This utility has two sides to its business: a regulated utility operation in Florida that backstops its investments in its Energy Resources Division, which is where it builds renewable power projects. The power from those projects is generally sold under long-term contract to other companies, notably other utilities. The two divisions provide a modicum of balance to the company's top and bottom lines.

At the other end of the spectrum are relatively small companies like Clearway Energy. Basically, the main business here is owning renewable power assets and selling the power under long-term contracts to third parties. (It owns five facilities labeled as conventional, representing about a third of its capacity; the rest is "clean" energy of some sort.) The sanctity of its long-term contracts is all that underpins the company's future revenue and earnings. Historically, that hasn't been a problem, but it's still the early days in the push toward renewable power.

Which brings up Southern Company (SO +0.14%). Like NextEra, it owns regulated assets and a renewable power business. But during the company's fourth-quarter 2018 conference call, CEO Thomas Fanning and CFO Andrew Evans both expressed concern about the renewable power space. Essentially, Southern was pulling back from building renewable power for other companies because of increasing risks. That included contract-related issues (less desirable returns and protections) and counterparty-related risks (less desirable customers, financially speaking). This pair's statements didn't really make any waves at the time; it looked like a historically conservative company was just being, well, conservative.

What just happened?

That all changed in early June when a judge decided that bankrupt PG&E could reject contracts it signed for renewable power. NextEra (eight contracts) and Clearway (six) both operate renewable power projects that sell electricity to PG&E. The ruling is actually a little complex in that it technically stated that the bankruptcy court has jurisdiction over the PG&E bankruptcy process and that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) can't get involved in the contract issues here. But the effect is that FERC, which would prefer to see reliable and safe power markets, can't at this point stop PG&E from killing contracts with key suppliers. Rejecting these contracts could have the end effect of impacting grid reliability.

Here's the thing: Those contracts were signed at a point when renewable power was more expensive. They are, effectively, above market today. So, working through bankruptcy, PG&E is right to push back and try to lower its costs by reworking these contracts. Suppliers like NextEra and Clearway, however, have more at stake. There are only just so many customers to whom they can sell the power these assets generate, and accepting lower rates will hit their top and bottom lines. They are between a rock and a hard place.

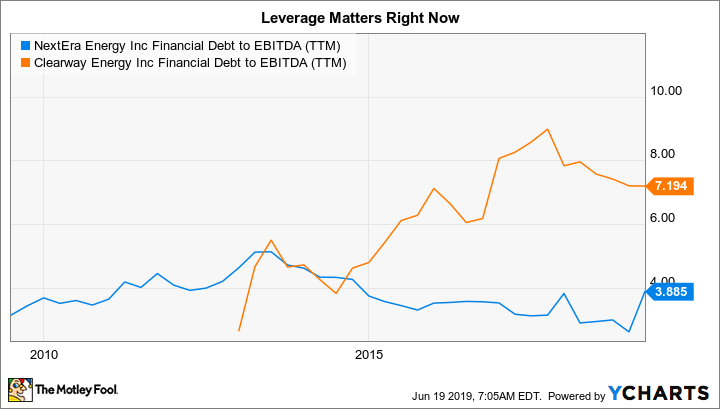

But, to paraphrase Warren Buffett, when the tide goes out you see who's not wearing swim trunks. And in this case, NextEra Energy's diversified business model is clearly the stronger one. Maybe it takes a hit on the handful of projects selling power to PG&E, but it can handle the blow because of its size, financial strength, and the large foundation provided by its regulated assets in Florida. It didn't even bother to make a public statement about the issue.

NEE financial debt to EBITDA (TTM) data by YCharts

Clearway is a completely different story. Renewable power projects are basically the core of its business. Add in a highly leveraged balance sheet, and the hit from PG&E's bankruptcy could be big trouble. To management's credit, it acted quickly, but shareholders may not be so happy. Even before the court ruling noted above came out, Clearway had announced that PG&E's bankruptcy had pushed it to trim its dividend by 40%. It's a good thing it acted in advance, since the worst-case scenario looks like it is unfolding and there's really no backstop to protect investors.

Is that a chill in the air?

Clearway isn't the only relatively small renewable power company out there, but it highlights the very real risks in the space that Southern has been noting. Small, focused renewable power companies have few options but to keep growing their renewable asset base, but the risks inherent to their business models are no longer hypothetical -- they are very real. What happens now is anyone's guess, but it's likely that increasing caution will be the norm in the renewable power industry. For investors, meanwhile, the outcome here highlights once again why taking a cautious, diversified stance can be so valuable. And that means sticking to giants like NextEra and Southern -- companies that have more to backstop their businesses (and dividends) than just renewable power contracts that may or may not be as safe as Wall Street thought they were.