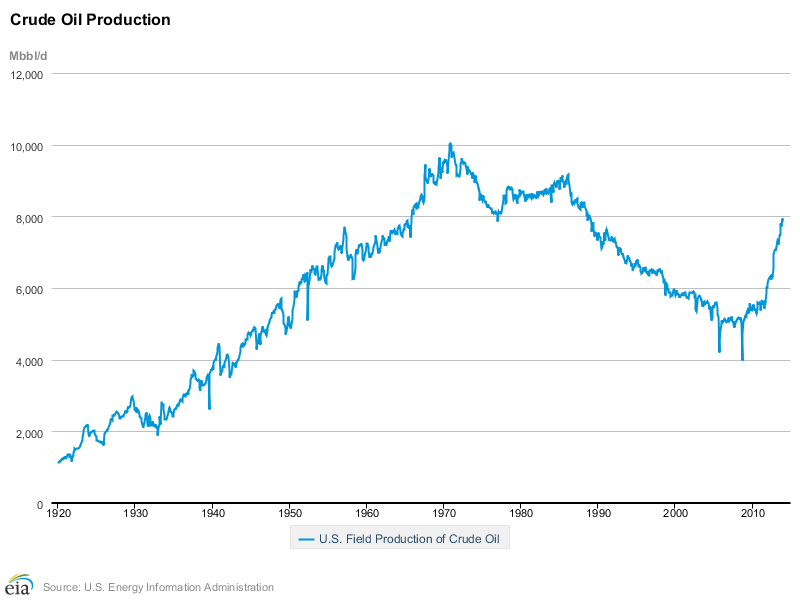

Even if you don't follow the energy industry, there is a good chance you know that the United States is producing more oil than it has in a quarter century. This chart showing domestic oil production since 1920 pretty much sums it up:

Americans haven't seen this much oil coming up from our own soil since the 1990. So why does the well-respected head of an investment firm with more than $100 billion in assets think it's a waste of time? Simple: It costs too much.

Jeremy Grantham, founder and head of the global investment management firm GMO, has an excellent reputation in the investing community; his calls on the dot-com bust and the housing crisis lend themselves well to that sort of thing.

Beginning his career as an economist at Royal Dutch Shell (NYSE: RDS-A), he now exhibits some of the characteristics of an environmentalist. That said, he remains fiercely pragmatic, and his opposition to investing in oil is primarily a fiscal one. He writes in his most recent quarterly letter to investors:

Our remarkable 20% increase in output is only 2% of world production. The real oil problem is its cost -- that it costs $75 to $85 a barrel from search to delivery to find a decent amount of traditional oil when as recently as 15 years ago it cost $25.

The cost issue is what gave rise to our oil boom to begin with, as producers utilized special expensive techniques like horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing in the vast majority of wells drilled in shale plays like the Bakken and Eagle Ford. The cheap oil prices of yesteryear would never have supported the cost of those techniques.

Grantham again:

Photo credit: Joshua Doubek.

... Fracking is not cheap. The fact that increased fracking has been great for creating new jobs should give you some idea: it is both labor- and capital-intensive compared to traditional oil. Also, we drill the best sites in the best fields first, so do not expect the costs to fall per barrel (although the costs per well drilled certainly will fall with experience, the output per well will also fall).

A recent article in Bloomberg points out the sheer volume of capital needed to sustain production in the Bakken oilfields of North Dakota, an area that will require 2,500 new wells drilled each year to keep oil production at current levels. It is fine for now, because capital markets are loose and the price of oil remains high, but if either of those factors changes -- markets tighten or oil prices drop -- it could have a massive impact on the U.S. oil industry.

The cost issue is already a problem for global giants like ExxonMobil (XOM 0.51%), Chevron (CVX 0.64%), and Royal Dutch Shell. These behemoths are spending more and more cash to produce less oil, as the world's so-called "easy oil" is gone, leaving the oil majors with oil is that is expensive to find and even more costly to produce.

Consider this data from The Wall Street Journal that shows the rates of capital expenditures and production over the last five years at ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, and Chevron:

|

Oil Major |

Capex Change |

Production Change |

|---|---|---|

|

ExxonMobil |

51% |

6% |

|

Royal Dutch Shell |

39% |

1% |

|

Chevron |

89% |

(3%) |

Source: The Wall Street Journal.

Despite massive inflows of capital, results have yet to pan out. Even when you take into account the fact that these massive projects can take years to come online, expensive projects started a decade ago have fallen far short of expectations.

The Kashagan field in Kazakhstan is a perfect example of that. A veritable who's who of big oil companies started exploring the region in the 1990s, and to date, the field has delivered little oil and lots of problems. You can add Shell's decade-long $5 billion fiasco in the Arctic to the list as well, as that project, still in the exploration stages, is currently on hold.

Increasingly, Grantham isn't the only one expressing concern about the future of the industry. Consider this recent note on ExxonMobil from two Oppenheimer analysts:

[ExxonMobil], like the rest of its peers, is facing an uphill battle maintaining, let alone growing, its production, as the low-hanging fruit has already been picked. Higher capital spending, rising costs, and increasing government take have squeezed earnings and reduced returns.

The analysts go on to recommend the oil giant abandon production targets and instead work to improve per-share metrics. But is it already too late for investors? As Grantham writes, "Even when considering oil, with enough progress in alternatives and in electric vehicles one begins to wonder whether this year's $650 billion spent looking for new oil will ever get a decent return." It is certainly food for thought.