I want you to imagine a world without Google (GOOG 0.07%). Right off the bat, at least half of you would have to imagine a different way to browse the Internet, either on a desktop or on a mobile device. You'd probably have to retrieve information on a different search engine, get directions from MapQuest or a stand-alone GPS device, and get your laughs from cat videos served up by something other than YouTube.

You could still do all the things that Google enables you to do today, but your experience would be ... different, and arguably worse, as each of the Google services I've just described are either the most popular options in their category, or very near to it. It's also quite possible that you wouldn't be hearing about things like Google Glass, the self-driving car, Google Fiber, modular smartphones, or any other of a host of Google-driven technologies.

Google's first server, from net neutrality days.

Source: Steve Jurvetson, Wikimedia Commons.

This world might see other companies step into the space Google now occupies, but it might very well not. You see, this world is one where consumer access to Google, and vice versa, doesn't flow as freely as access to other companies who started earlier and built up their war chests first. This is a world -- or rather, a United States -- that's never heard of net neutrality, where an Internet service provider, or ISP, can force data it doesn't like to pay a toll to get to its subscribers. In this world, innovation isn't the buzzword it is in ours, because real innovation is frequently stifled by de facto data monopolies that can afford to pay for a fast lane on the information superhighway.

Remember that phrase? It was pretty popular before dot-com boomed, and the state of the Internet in those days is not something to which we should want to return. But if Comcast (CMCSA +1.74%) and Verizon (VZ +11.81%) get their way, tomorrow's children might very well be using the same phrases for their online experience that we do with ours, because they won't enjoy the rapid change in connected technology that we now take for granted.

The Internet, which has been built on the principles of open and equal access for all legal businesses to all potential consumers, has generated so much change so rapidly in both our culture and its own industry precisely because all data was equal and all pathways were open. If the country's largest carriers get their way, this openness is likely to be replaced by a pay-to-play system that gives incumbents a locked-in advantage over savvy upstarts with better ideas for better services. At that point, what you end up with is not so much a culture of innovation as a system of sclerotic data monopolies -- a description that, quite unfortunately, already applies to America's major ISPs.

Neutrality in a broadband age

Net neutrality was not much a matter of public interest in the United States until after the turn of the 21st century, when consumers began subscribing to broadband Internet service in large numbers. Before broadband, you were lucky if you could download a single MP3 (those oft-copyrighted music files that got Napster in so much trouble) in 10 minutes, so there wasn't that much of a business impetus to promote data-intensive services online. Today, 70% of American adults can download that same file in a few seconds over their broadband connection. Today, the businesses that can serve up those files -- or videos, or social-media photo albums, or online game experiences, or anything else that depends on speed for an enjoyable experience -- most efficiently can stake a claim to a constantly growing pie worth billions of consumer dollars.

A relic of the dot-com Internet era.

Source: User NapInterrupted via Flickr.

ISPs have been fighting back against net neutrality for far longer than you might think. The Federal Communications Commission promulgated its first official net neutrality policies in 2004, and it took less than a year after that announcement for the agency to drag an ISP to court for data discrimination against a voice-over-IP service. As early as 2007, lawmakers were raising the specter of stifled innovation on a pay-to-play Internet. That year, Sen. Byron Dorgan (D-N.D.) pushed the Federal Trade Commission to take a more active role in policing against ISP data discrimination, using much of the same language I've used at the start of this article:

Larry [Page] and Sergey [Brin, Google co-founders], just nine years ago, were moving to a garage with a garage-door opener, and had nine employees. That's nine years ago. And they had an idea. Nine years later, they have a company that exceeds the combined valuation of Coca Cola, Ford Motor, and General Motors. Now, would two guys in a dorm room or a garage have access to the consumers in X, Y, or Z city if the big interests said, "Oh, by the way, you get a shot to go on our toll road if you can pay the toll"? I don't know. I don't think consumers will ever know what they miss.

We created this Internet system through innovation. Innovation was available to everybody under every circumstance, and it was able to be accessed by everybody under every circumstance. If we get to a point where we say, "Now there's no nondiscrimination rules, there's no rules against discrimination, you can discriminate," we won't know what we miss. We won't know what innovation we squelch.

Cable companies like Comcast and telecoms like Verizon only began extending themselves from their core businesses into broadband Internet service around the turn of the century, when only 3% of Americans had a broadband connection. However, by that point, consolidation in both cable and telecom industries was already well under way -- from the early '90s to the present day, a roster of 42 American cable companies shrank to four, and only five major telecoms remain of the 17 that once operated. The seven companies that provide high-speed Internet access boast a combined subscriber roster of nearly 71 million out of the roughly 83.6 million total broadband subscriptions in the United States.

In most industries, seven major providers would be ample evidence of competition, but the reality of online access is that you're pretty much stuck with one option nearly anywhere in the country. Comcast's recent push to buy Time Warner Cable (NYSE: TWC) -- a clearly anticompetitive maneuver that has nonetheless been met with an apathetic shrug from the FCC -- would create a monster that would serve more than a third of the entire country's cable and broadband Internet subscriptions, even after the new company divested some 3 million subscriptions to placate regulators. For most of the people and businesses operating in 19 of the 20 largest metropolitan areas in the country, this supersized Comcast would be the only path to wired broadband Internet access. Its combined service area includes upcoming high-tech hotspots such as Austin, Texas; Washington, DC; Seattle; Boston; New York City; and, yes, Silicon Valley as well.

Data wants to be free

Let's be clear that when we speak of the dangers of losing net neutrality, we're not talking about Netflix's (NFLX +0.37%) recent deal with Comcast to ensure that its streamed movies are more dependably delivered to Comcast's subscribers. Content providers have entered into these deals with ISPs for years, and before building out its own content delivery network, or CDN, Netflix simply used third-party CDNs with their own similar deals ensuring stable service. When we talk about losing net neutrality, we're envisioning a world in which Netflix does not get off the ground at all. Comcast owns part of Hulu, a separate streaming-video service, and although it's currently not active in its management under regulatory restrictions, it's not hard to imagine a world where the ability to discriminate between different streams of data would lead Comcast to favor its own video services at the expense of competitors.

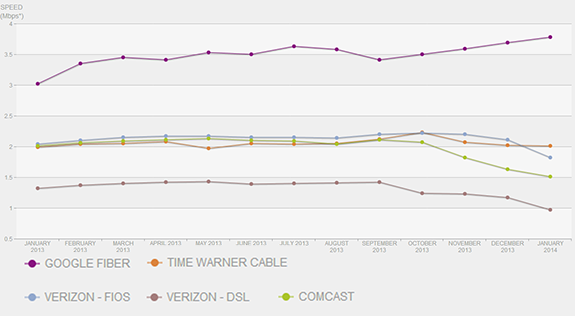

We can actually see the way this has played out in recent months thanks to Netflix's data on major ISP streaming speeds, which shows a distinct decline in the speed provided to Comcast and Verizon subscribers over the past year:

Source: Netflix. Click here for full-size view (opens in new window).

Two weeks ago, Netflix actually claimed that the slowdown on Verizon and other broadband ISPs was connected to pay-to-play disputes, and the publication of this grievance and the data you see above was no doubt meant to cow those ISPs into backing down. Instead, Comcast won the first battle, and it seems likely that Verizon will extract similar concessions from Netflix in the weeks to come. But this is not the real threat -- what should worry you is that, if a better service than Netflix somehow gets off the ground, it will be stifled by collusion between Netflix, Comcast, Verizon, and others who would all have a serious financial stake in perpetuating the status quo. Netflix didn't start off streaming a third of all data delivered to American Internet subscribers, but its path to that position would have been far more difficult if ISPs had pushed back against it in favor of their own service from day one.

In a broader sense, American ISPs are already pushing back against data-intensive services by simply being awful at providing globally competitive connection speeds. Netflix's data on ISPs in other countries show that speeds of 2, 3, or more megabytes per second, or Mbps, are the norm throughout Europe, and even in Mexico, Brazil, and Chile, most ISPs provide faster access to Netflix than Comcast does in the United States. The U.S., which invented the Internet, is now ninth in average connection speeds among all countries, 15th in broadband adoption per capita, and 21st out of 33 countries in terms of the cost of a full year's broadband subscription. America's mobile broadband speeds are even further behind the curve -- average U.S. 4G LTE speeds of 6.5 Mbps are roughly half that of the next-fastest nation, slower than all other widely connected 4G nations except the Philippines, which boasts 5.3 Mbps.

The four largest broadband ISPs -- Comcast, Time Warner, Verizon, and AT&T -- reported roughly $63 billion in combined broadband service revenue from more than 57 million subscribers last year. Each of those households was likely to access approximately 80 gigabytes per month of data, for a total of 51 exabytes of data for the full year, which is about the same amount of data as is contained in 12.8 billion DVDs. The companies that created most of that data -- the world's four largest Internet companies, all of which are based in the United States -- generated $158 billion in revenue last year. E-commerce sales in the U.S. alone reached $384 billion in 2013, and online advertising revenues from U.S. Internet users added between $40 and $45 billion more to the tally. In a world without net neutrality, those four ISPs with their $63 billion in Internet-access revenue would be able to dictate to a large degree the path Internet-native companies take to generate hundreds of billions, and eventually trillions, of dollars in revenue.

The fix everyone wants but no one can stomach

Many of these issues, from slow connection speeds to high prices to unequal access, could be solved by simply acknowledging that Internet service is now an essential utility rather than a value-added service. In the past, slow speeds and patchy connectivity and underdeveloped online environments made the Internet a curiosity, like electricity once was for the few wealthy New Yorkers who first got to marvel at Edison's light bulbs. But electricity eventually became indispensable and thus fell under the aegis of government regulation, and so should Internet service.

As The Verge's Nilay Patel has argued, data is not a luxury; it's a commodity. A situation in which large manufacturers conspire with their power companies to choke off electricity to competitors would be unthinkable, so why do we even want to entertain the notion that ISPs should be able to control access to online services on a case-by-case basis? If the future will be created online, the worst thing we could do as citizens and as investors would be to accept a future in which a very small number of powerful gatekeepers can pick and choose the data we get to see.

Comcast and Verizon are profit-driven entities without real competition in what is already a narrowly profitable industry -- Verizon's wireline segment brings in hardly any operating income despite accounting for a third of the company's total revenue -- so they have no real impetus to improve service and every motivation to fatten themselves on easy money, which could well include brokering deals with large incumbent content providers at the expense of smaller upstarts. That's not to say Netflix and other large online companies should have a free on-ramp to the Internet, but they shouldn't be able to create situations where competitors have to bribe their way online, if they're allowed the chance to bribe at all. What Comcast, Verizon, AT&T, and other large ISPs want is not what's in the best interest of the Internet, which drives the American economy forward more powerfully with every passing year.

The future of the Internet is too important to leave in the hands of a few profit-driven monopolies. As Americans, and as investors, we should oppose any situation in which these few companies might control the direction of data-driven American innovation.