Recently, co-founder and CEO of The Motley Fool Tom Gardner interviewed Michael Lewis, the author of Flash Boys. Before the two discussed the issue of high-frequency trading in depth, Lewis made a comment about ignorance. He noted that, particularly in the world of finance, investors are quite averse to admitting to a lack of knowledge.

He wasn't talking about Mom and Pop investors, either. Big finance's heaviest hitters, the CEOs and managers of hedge funds and other entities are the biggest offenders, said Lewis. Gardner pointed out that author Will Thorndike had taken a look at eight high-performing CEOs over a 20-year period, noting that the common characteristic among them was that they were all industry outsiders.

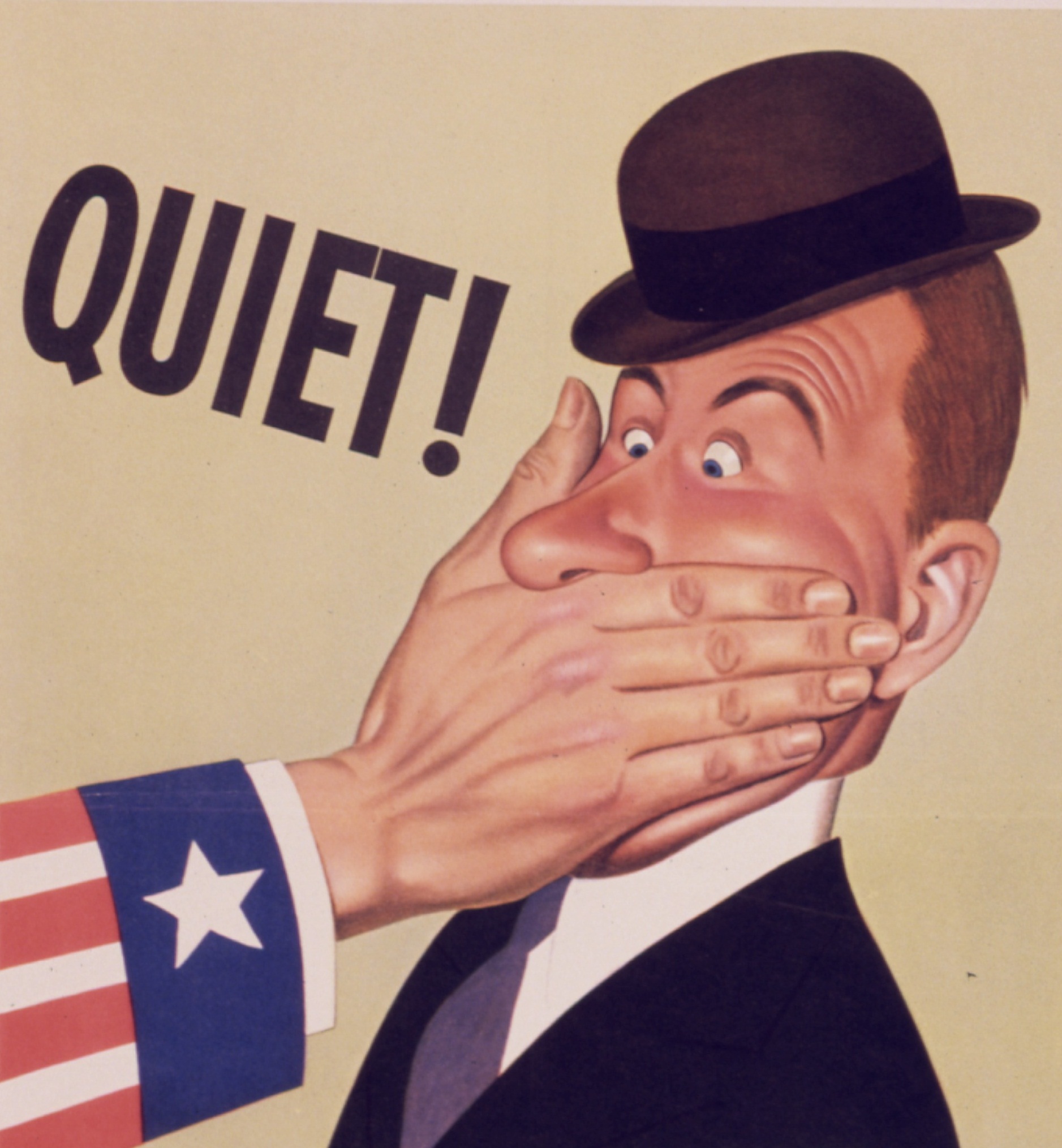

With no reputation to uphold in the new sector, these leaders were free to learn from others, and say what insiders – particularly in finance – are loathe to:

"I don't know."

An affliction that can affect anyone

This theory makes sense, and explains a lot about the financial crisis. As Lewis says, no one really knew what subprime collateralized debt obligations were, or if such CDOs were truly worthy of AAA ratings. New financial instruments were being created at the speed of light, and no one wanted to admit that they didn't understand much about them.

This mind-set afflicts consumers of financial products, too. Certainly, if more subprime borrowers had understood exactly what they were getting themselves into during the run-up to the housing crash, they would have been up in arms. Asking questions and doing some in-depth research may have saved countless lives from ruination.

The same goes for smaller investors. If victims of Bernie Madoff had asked more questions, might they have been spared their fate? It seems likely. In an interview last June with MarketWatch, Madoff identified a red flag: If something sounds too good to be true, it is. He noted that he was able to continue with his scam for so long because no one ever questioned him.

He drove home the concept further:

Wall Street is not that complicated. If you ask an average hedge fund or investment firm how they make their money, they won't tell you. Most people think it's too complicated and they can't understand it. You should ask good questions and, if you don't understand something, have your accountant ask questions.

If you don't understand something, then don't invest in it. People asked me all the time how did I do it, and I refused to tell them, and they still invested with me. My investors were sophisticated people, smart enough to know what was going on and how money was made -- but still invested with me without any explanations. Things have to make sense to you. If you don't understand the investment, don't put your money there.

Were Madoff's sophisticated clients afraid of being considered stupid? Possibly. After all, many were already rich when they opted in with Madoff, and, as such, were probably used to being thought of as knowing everything, as Lewis suggests.

Studies have shown that everyday investors often suffer from the inability to admit ignorance, as well. Investors invariably fail at investing by using emotion, rather than information, to guide their investment thinking. They buy when a stock is hot, and the price is high – then sell in a panic when the price is falling. While the average equity mutual fund returned 8.18% over a 10-year period ending last December, average investors made only 6.52%.

Markets have good years and bad years, of course. Long-term investors understand this, and generally do better because of it. They've done their homework, because they know that performing due diligence is vital to success in any endeavor, and investing is no different. To succeed, read, learn, and ask questions. And, if you don't understand the answers, don't be afraid to say so.