Over the next month, banks will be releasing results for the second quarter. In advance of these releases, let's take a moment to review the state of some of these banks as of the end of Q1.

Today, we'll look at Bank of America Corporation (BAC +0.96%), a $2.1 trillion bank headquartered in Charlotte, N.C.

When I evaluate banks, I follow a model made famous by former Wachovia CEO John Medlin: soundness, profitability, and growth. As investors, we then look at valuation and the potential for investment after gaining a better understanding for each bank.

Soundness

Soundness refers to the bank's asset quality. Generally speaking, this means loans. If a bank makes loans that are never repaid, that bank will fail, and fail quickly. The best banks put risk management first, ensuring that shareholder capital is protected if a portfolio of loans turns sour.

To measure this, we'll look at both non-performing assets and Bank of America's provision for loan and lease losses. A simplified definition of non-performing assets are loans or other assets that have fallen seriously delinquent or are in foreclosure.

The provision for loan and lease losses is a reserve of money that the bank pulls out of its income each quarter to guard against future losses in the loan portfolio. Banks are required by regulation to maintain certain levels of reserves, but within that, management has plenty of wiggle room to over- or under-reserve. Over-reserving increases protection but hurts net income; under-reserving increases risk but keeps net income high.

For the quarter ended on March 31, Bank of America had 0.85% non-performing assets as a percentage of total assets. The FDIC reports that banks with total assets greater than $10 billion on average had 1.5% non-performing assets as a percentage of total assets.

Bank of America reserved $1.0 billion for the first quarter, which represented 4.5% of operating revenue. That compares with 5% for the $10 billion-plus peer group, according to the FDIC.

For Bank of America, these figures tell only part of the story. The bank has been severely handicapped since the financial crisis by billions upon billions of dollars of regulator violations, failed mergers, and, most critically, bad loans. Current management has undertaken a massive reorganization of the bank to simplify operations and reduce risk -- in essence, the bank is finally putting soundness first.

Can the culture really change, though? Fellow Fool John Maxfield is skeptical, and so am I. Credit culture is part of a bank's DNA -- it doesn't change overnight, or even over a few years. It changes over multiple years, if ever at all. The recent capital miscalculation and suspension of a planned dividend increase are symptoms of this diagnosis.

Bank of America may be doing and saying the right things now, but over the long term, the bank's track record simply needs to indicate sustained success.

Profitability

After establishing an understanding of a bank's risk culture and soundness, next we can focus on profitability. Any investment in a business is an investment in that company's future earnings, so profitability is a particularly important consideration for any bank investor.

The first question, perhaps most obviously, is whether the bank generates a profit at all. According to data from the FDIC, 7.3% of U.S. banks failed to generate a profit at all in the first quarter. That's one in every 14 banks!

For Bank of America, the first calendar quarter of 2014 was pretty bad. For the first quarter, the company reported return on equity of negative-5% because of the net loss. Of the banks covered in this series of articles, the average return on equity was 8.9%. The FDIC reports that the average ROE for U.S. banks with total assets greater than $10 billion was 9.1%.

The company did generate total net revenues of $22.6 billion for the quarter -- that is total interest income plus non-interest income, minus interest expense.

And over the past 12 months, Bank of America generated $85.5 billion in total net revenue. Of that revenue, 45% was attributable to net interest income, the difference between interest earned on loans and paid out to depositors. The remaining 55% was through fees, trading, or other non-interest revenue sources.

The bank was able to turn a profit margin of 11% on that revenue, so all is certainly not lost.

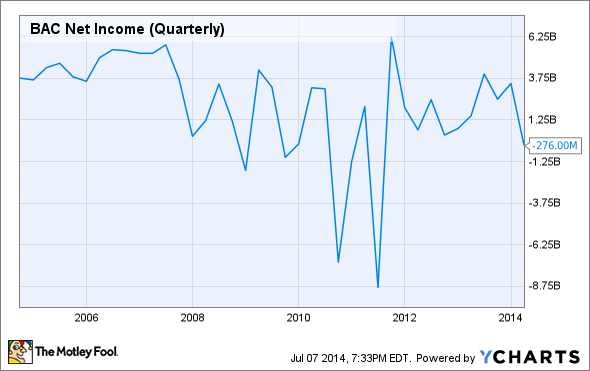

The issue with the bank's income statement today is not that it can't create revenue or even run a reasonable banking operation. The problem is massive, non-recurring charges resulting from the bad behavior before the financial crisis. Regulatory fines, Justice Department settlements, and heavy charges related to unscrupulous practices are wreaking havoc on the bank's profits.

Over the very long term, these charges will fade and the bank's true core earnings potential will shine through. Until then, expect volatility, uncertainty, and disappointment. And even at this point it's too early to know what the bank's true ROE potential will be.

Leverage

Leverage is a double-edged sword for banks and could easily fit into either the soundness or profitability categories. We'll call it a subset of both and discuss it here.

Leverage is just part of the game with banks, so if you're a conservative investor who really focuses on conservative capital structures, the banking industry may not be the best place for your money. Adding leverage is an easy way to juice return on equity, which is, generally speaking, a good thing. The bank increases assets and thus earnings, while maintaining a lower capital level.

The result is a higher numerator, a constant denominator, and a larger return-on-equity number. The math does the heavy lifting for you.

BAC Return on Equity (TTM) data by YCharts

On the flip side, too much leverage can put the bank on thin ice if the loan portfolio takes a turn for the worse. A stronger equity base protects the bank from bankruptcy and bailouts, two outcomes that are both politically charged and downright terrible for shareholders.

Banks use all kinds of esoteric and overly complex accounting methods to determine leverage. We'll keep it simple here with an old-fashioned assets-to-equity ratio. The lower the number, the less levered (and more conservative) the bank.

Bank of America's assets-to-equity ratio comes in at 9.3. The average of the 62 banks analyzed in this series of articles was 9.1.

BAC Assets To Shareholder Equity (Quarterly) data by YCharts

That said, appropriate leverage for an institution is not quite as easy to peg based on peer comparison alone. A highly leveraged bank with volatile profits and a high-risk balance sheet is far worse than a highly leveraged bank with rock-solid profits and a low risk profile. At this point, it should be clear which camp B of A falls into.

Growth and valuation

Bank of America saw its revenues change by 14% over the past 12 months. That compares with the 5.7% average of the 62 banks analyzed.

Fifty-four percent of all U.S. banks saw year-over-year earnings growth in the first quarter; Bank of America was part of this group -- kind of. The bank didn't grow "profits" per se, but it did lose less money.

Moving now to valuation, Bank of America traded at a forward price-to-earnings ratio of 11.9, according to data from Capital IQ. That compares with the peer set average of 16.67.

Bank of America's market cap is, at the time of this writing, 1.1 times its tangible book value. The peer set average was 1.9.

Many investors use a general rule of thumb of buying a bank stock when the price-to-tangible book value is less than 0.5 and selling when it rises above 2. For me, that method is just way too oversimplified.

It sometimes makes sense to pay a premium for a bank stock that places a high value on credit culture and asset quality. These banks will survive and prosper while others fall by the wayside. That security can be worth a premium. Likewise, a bank that relies heavily on leverage to achieve above-average return on equity may not be worth the price, even if price-to-tangible book value is low. That risk may not justify even a healthy discount in price.

Based on the factors we've discussed here -- soundness, profitability, and growth -- Bank of America simply doesn't make the cut.

Yes, the bank appears to be undervalued based on P/E and price-to-tangible book value. But just because a bad business is cheap doesn't mean it's a buy. If you're looking for a bank with real long-term potential -- the kind of stock that can stay in your portfolio for decades -- then look elsewhere.