Diving into the details of the LCR, HQLA, and a bank's net cash

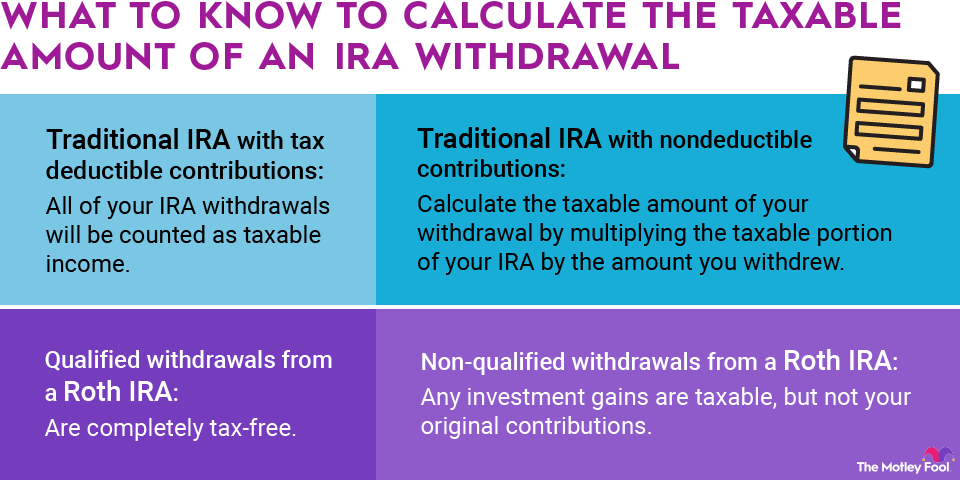

A cornerstone of the liquidity coverage ratio is the concept of high-quality liquid assets. In the past, banks were allowed to count a myriad of different investment securities as liquid assets. In normal times, these assets, like mortgage-backed securities, are, in fact, liquid. However, in a crisis, the market for these assets can dry up, rendering them illiquid and useless in meeting short-term cash needs.

The new regulations work around this problem by defining exactly what assets can be considered "high quality," ensuring that only assets with near-certain safety in normal times and in a crisis can be considered. For general purposes, banks' high-quality liquid assets consist of U.S. Treasury securities and actual cash.

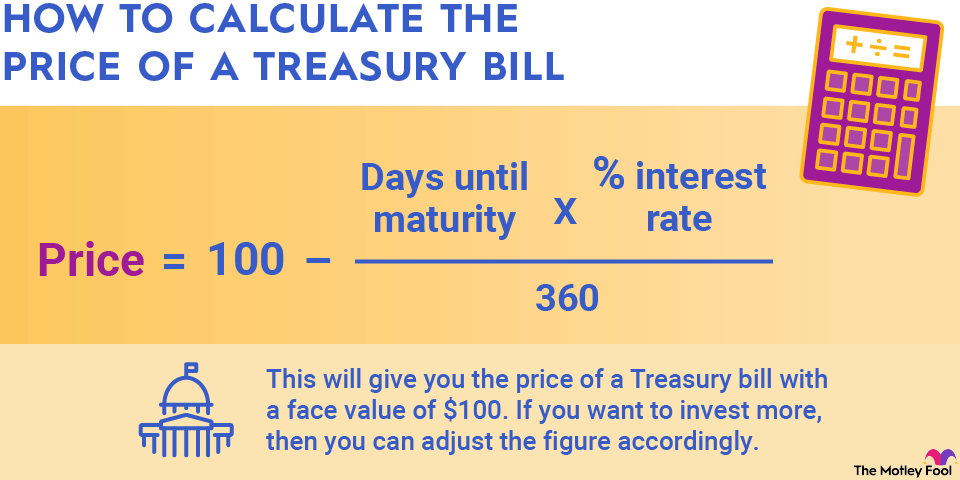

The denominator of the ratio is a bank's "total net cash outflow." This number is determined from a complicated accounting calculation.

At a high level, it's the 30-day total of all withdrawals from deposit accounts, cash outflows to fund loans, cash expenses from the bank's operations, and the cash outflows it needs to comply with derivative, investment, debt, and other contractual obligations not included elsewhere. That outflow is then netted by all the various sources of cash that come into the bank over a 30-day period. To be clear, it's a very complex accounting process.

Once all that work is complete, the two numbers are divided, and we have the LCR, which is the best way to assess a bank's liquidity position.

As an investor, your job is much simpler than the bank's. Investors just need to open up the bank's quarterly financial report and scroll down until you see the reported liquidity coverage ratio. The higher the ratio is above 100%, the stronger the bank's liquidity position.

Related investing topics