Every publicly traded company issues a series of financial statements on at least a quarterly basis. The balance sheet is perhaps the statement most indicative of a company's financial health.

A company's balance sheet contains important information about how much money the company has, how much it owes, and more. In this article, we'll discuss the basics of balance sheets, how they work, what to focus on as an investor, and a real-world example.

How balance sheets work

A balance sheet is a financial statement that shows a business's current financial state and calculates the book value, or investors' equity, in the company. A balance sheet has three main components: assets, liabilities, and shareholders' equity. In the next section, we'll get into what information is included in each one.

Balance sheets are important for investors to read because they can answer some very important questions about a company's financial health and flexibility. By knowing how to read a company's balance sheet, you can find the answers to questions such as:

- How much cash does the company have available to make acquisitions or invest in growth?

- How much tangible property, such as factories and machinery, does the company own?

- How much debt does the company have?

- What is the company's actual book value?

The balance sheet formula

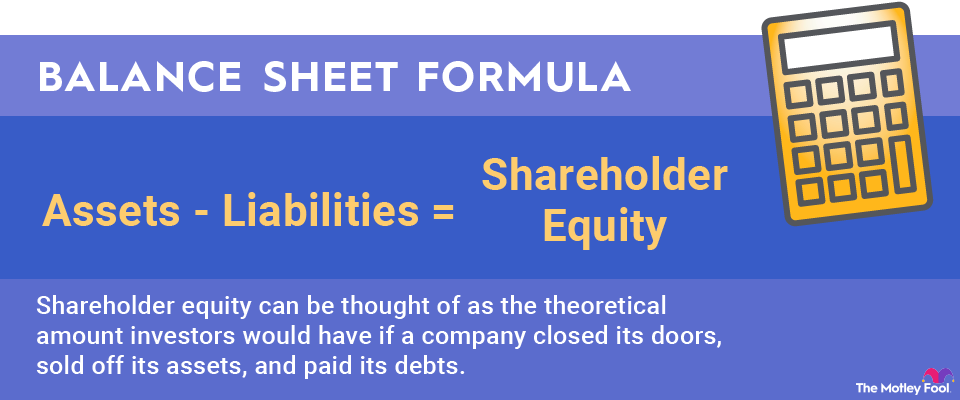

Although a balance sheet itself can be quite complex and difficult to understand for many investors, the central concept is rather simple:

Rearranging this equation a bit shows that assets minus liabilities equals shareholders' equity. Also known as a company's book value, shareholders' equity can be thought of as the theoretical amount investors would have if a company closed its doors, sold off its assets, and paid its debts.

Obviously, a large company would be unlikely to do that, but the idea is similar to how home equity works. If your home's value is more than what you owe the bank, you have positive equity.

Elements of a balance sheet

As previously mentioned, a balance sheet has three main parts: assets, liabilities, and shareholders' equity. Let's take these one at a time.

Assets: The short explanation is that assets include everything a company owns. Assets are typically broken down into current and non-current assets. Current assets include liquid assets, such as cash and short-term investments. They also include assets expected to become liquid within a year, such as inventory and accounts receivable.

Asset

Noncurrent assets include things that won't be readily spendable within the next year. Tangible property, such as a factory, is the most obvious example. However, they also include equipment, long-term investments, and intellectual property.

Liabilities: Most notably, the liabilities category includes a company's debts. Like assets, liabilities are separated into current liabilities (those due within a year) and noncurrent liabilities. Debts coming due soon and accounts payable are examples of current liabilities you'll typically find on a balance sheet, while long-term debt is the most common type of noncurrent liability.

Liability

Shareholders' equity: Subtracting the company's liabilities from its assets shows its shareholders' equity. The metric itself is most useful when evaluating value investments, as opposed to growth stocks, because it shows what a business is "worth" based simply on what it owns and owes without regard to its income-generating or growth potential.

Statement of Shareholders’ Equity

It's also worth mentioning that shareholders' equity and a company's market capitalization (the market value of its stock) are often very different numbers. That is especially true if a company can generate high returns on its assets or it's growing rapidly.

Example of a balance sheet

Let's look at a real-world example of a balance sheet and how to read it. Here's a shot of Apple's (AAPL -1.31%) balance sheet as things stood on Sept. 30, 2023:

Assets

Let's start with the assets section. When you hear that a company "has a lot of cash," it typically isn't actually holding all of it in cash. The "cash and equivalents" category on the balance sheet contains actual cash, as well as instruments like money market accounts.

However, the current and noncurrent assets categories also include "marketable securities" categories. These contain things such as Treasury securities, bond investments, and stocks.

The key point is that these can typically be readily converted into cash the company can use. So, while Apple has roughly $30 billion in actual cash and equivalents, this figure swells to more than $162 billion when considering marketable securities.

Second, it's important to realize that aside from cash and marketable securities, other values listed in the assets section aren't set in stone. For example, there's no guarantee Apple could sell its property, plant, and equipment holdings for the $43.7 billion listed.

The $6.33 billion in inventory listed assumes it will all sell for full price, and the $29.5 billion in accounts receivable assumes 100% of Apple's customers will pay their bills. And "other assets" is the vaguest of all, typically including the value of things such as patents, goodwill, and other difficult-to-value items. With that in mind, we can see that Apple has a total of about $352.6 billion in assets on its balance sheet.

Liabilities

The biggest liability on Apple's balance sheet is its long-term debt, which stands at about $95.3 billion. It also has a smaller amount of short-term debt plus about $63 billion in accounts payable (e.g., to its part suppliers). Although Apple has almost $109 billion in current and noncurrent "other" liabilities -- certainly a lot of money -- the key point is that this is a very broad category.

On the current side, this can include things like payroll obligations, accrued benefits, and other items due within a year. On the noncurrent side, liabilities can include lease obligations, deferred tax credits, customer deposits, and pension obligations, to name just a few. In all, Apple has about $290.4 billion in liabilities reported on its balance sheet.

Shareholders' equity

When we subtract Apple's liabilities from its assets, we see that its shareholders' equity is about $62.1 billion. As noted, think of this as the amount of money that would theoretically be left if Apple decided to cease business operations, sell everything it owns, and pay off its debts.

This is not a measure of how much the business is worth. Apple is a highly profitable and efficient business growing rather quickly, even with its large size. In fact, Apple's market value is currently about $2.7 trillion -- about 43 times its shareholders' equity or book value.

Again, shareholders' equity is most useful when evaluating value stocks and comparing stocks' valuations in similar industries. For example, the price-to-book (P/B) ratio is especially useful when evaluating bank stocks since other common valuation metrics (like the price-to-earnings ratio) aren't always a great fit.

Related investing topics

How to create a balance sheet

If you own a small business or simply want to analyze your personal financial condition, a balance sheet can help you tremendously. You can start by listing your assets, including your cash, investments, accounts receivable (money you're owed), any inventory you own, property you have, and so forth.

Next, list all the debts and other obligations you have. You can find some excellent balance sheet templates online that can help keep you organized. Subtract the liabilities on your balance sheet from the assets to find the equity you have in your business or your personal net worth.