Investing in a company largely comes down to an assumption that it can generate economic value for shareholders. We love talking about the positives, such as strong balance sheets, brand power, and all of the other things that can lead to strong cash flow generation. We love those strong assets.

But companies also have liabilities. On the surface, it's a word that sounds bad; the way we use it in daily language rarely has a positive connotation. How many times have you heard the worst player on a sports team described as a liability?

When it comes to evaluating a business, a liability is really just a one-word description of what a company owes to other parties. It’s time to lose the negative connotation -- at least in the investment world -- and gain a better understanding of the purpose of liabilities and how they fit into the bigger picture.

What are liabilities?

When looking at a company's balance sheet (one of three financial statements investors should understand), there are basically two main categories: assets and liabilities. Assets are things that a company owns (such as cash, inventory, and property), and liabilities are things a company owes to other parties. Here are some examples of common liabilities:

- Debt

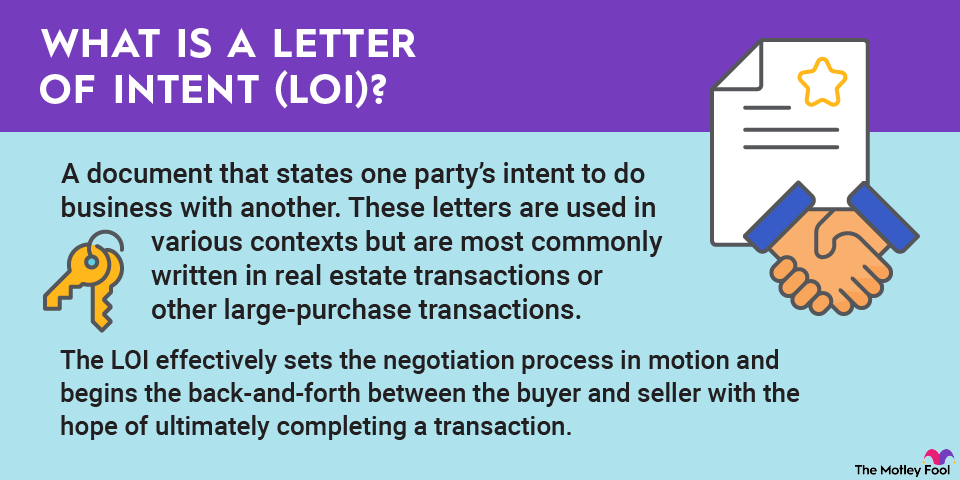

- Lease obligations

- Accounts payable

These are the most typical and straightforward liabilities for companies. They borrow money, sign long-term contracts to lease property and equipment, and owe money to suppliers.

Companies should also have something on the assets side of the balance sheet to offset a liability. For example, a company may issue debt to expand its manufacturing, with the assets being the new factory and the equipment it purchased (which would show up under "property, plant, and equipment”). With leases, the asset is the remaining economic value of the leased property. For accounts payable, the offsetting asset is the economic value of what it bought, such as inventory.

Liabilities that may not seem like liabilities

Some company liabilities may not seem like liabilities, which explains the importance of the core definition. Here are two examples:

A bank would list deposits as a liability. You may wonder how that is a liability. The deposit is money it owes to its customers. The asset -- this is the offsetting part we discussed above -- is the cash that it got from the depositor. The bank will take the cash and use it to fund its operations and lend to other customers while retaining only a small portion to cover the regular day-to-day turnover in deposits.

Deferred revenue is another liability that might not seem like a liability. After all, this is future revenue. Still, even though the company has already gotten cash from the customer, it hasn’t yet delivered anything to the customer. It also hasn't recognized all of the expenses related to what it owes the customer. As a result, it must offset what it's gotten for what it still owes and then recognize the revenue and expenses related to it when it delivers to the customer.

In both of these examples, the lesson is that a liability isn't necessarily a bad thing; it's just a way to measure what the company still owes another party.

Related investing topics

How to use liabilities to make better investing decisions

The key to using liabilities for better investing decisions is understanding how liabilities fit on a company's balance sheet and how they affect its operations, and whether the balance of liabilities and assets is likely to result in economic growth.

For example, if a company uses debt to finance an acquisition, it may add "goodwill" as an asset to its balance sheet if it paid more for a company than its fair value. In this case, the warning flag was the goodwill asset -- signaling the company may have overpaid for the acquisition -- while the liability, or the debt for the overpriced acquisition, will still have to be repaid since it impairs the goodwill.

It's also important to understand different liability exposure for companies in different industries. For example, REITs (real estate investment trusts) use a lot more debt than software companies. But they use that bigger debt for good reason. A 20-year-old apartment building is probably worth more than when it was built; 20-year-old software probably isn't.

Inventory

So looking beyond the offsetting asset, it's useful to understand how -- and if -- a liability is leading to higher returns. Was a big loan used to build a more profitable factory? If a retailer buys a lot of inventory, can it sell for more than the amount owed on the accounts payable side of the ledger, or will the retailer have to discount excess inventory?

In summary, liabilities aren't bad or good. They’re just one part of measuring a company's balance sheet. From there, understanding how that balance sheet either helps or hinders a company's progress will help you become a better stock picker.